Ed Halter

Ed Halter

A biography by John Szwed portrays the bohemian polymath and avant-garde artist and filmmaker in all of his uncategorizable splendor.

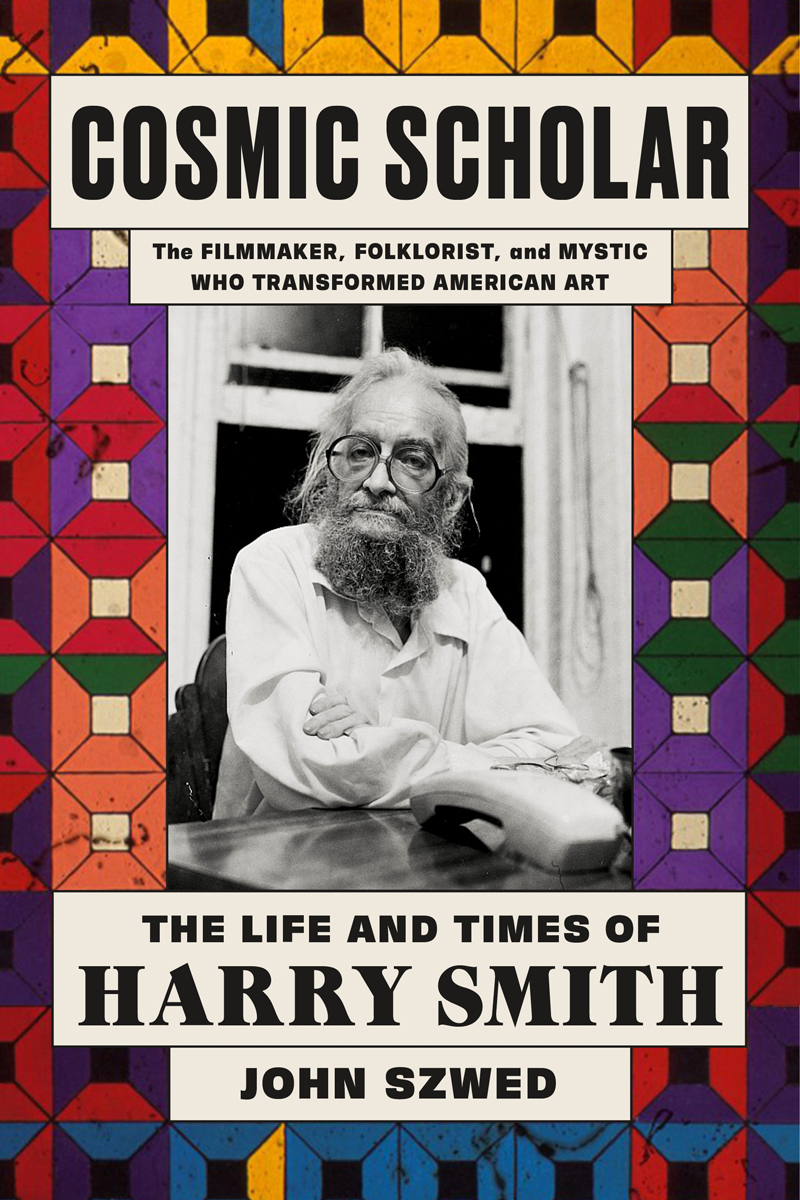

Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith, by John Szwed, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 404 pages, $35

• • •

In 1973, the fabled artist, filmmaker, and polymath Harry Smith (1923–1991) composed a letter to a grant agency asking for additional money to help complete what would be his final motion picture, Mahagonny, also known as Film No. 18. Smith reported that he had been toiling on it for seven years, blaming its delays and overcosts to his own mental derangement: “As the sort of film I make is ‘improvised’ according to the dictates of a diseased brain I can never tell which direction it’s going to jump.” When it finally premiered in 1980, Mahagonny was realized as an epic multiscreen montage with oblique correlations to Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, an opera that had long been one of Smith’s numerous obsessions; he listened to a more than two-hour recording of the piece multiple times a day for decades. “Mahagonny is particularly difficult,” he explained to his funders, after confessing that he had accepted the grant while drunk. “You have to live Mahagonny, in fact be Mahagonny in order to work on it . . . You must remember that I spend all my income on one thing or another directly connected with making Mahagonny by living through the birth and death of Mahagonny myself.”

Veteran biographer John Szwed appears to have faced a similar, all-encompassing conundrum when researching Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith, though hopefully not to the point of Smith’s chronic destitution. Touted as the first book to tell the life story of one of the mid-twentieth century’s most consequential bohemians, Szwed’s spirited account begins with the author facing the immensity of his task, wandering through a Brooklyn warehouse among the thousands of books and records that belonged to Smith, an insatiable bibliophage and compulsive collector. “I feel as if I am entering Jorge Luis Borges’s Library of Babel, a universe of books and records, or maybe a labyrinth of paper and vinyl,” a flabbergasted Szwed relates. “The temptation is to read and listen to every one of them in hopes of at least finding the meaning behind Harry Smith the reader and listener.” He adds, with pointedly Borgesian anxiety, that “maybe my book is in there, already written.”

American Magazine photo of Harry Smith, nineteen, at home with Lummi Indian Nation guests, 1943. From Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith. Courtesy the Harry Smith Archives. Photo: K. S. Brown.

Smith’s interests were expansively broad and deep, leading him to devour tomes on, among other subjects, linguistics, children’s games, alchemy, Buddhism, literary studies, psychology, and especially anthropology. A self-taught ethnographer, Smith began documenting the traditional song and dance of the nearby Lummi, Samish, and Swinomish peoples while still a teenager in Washington state in the late 1930s, writing notes, taking photographs, painting watercolors, and preserving audio with a cumbersome phonographic disc-cutter. These studies continued throughout his life, and the biographer states that, despite Smith’s achievements in art, film, and music, “he would always identify himself as an anthropologist.” Like his fellow traveler Alan Lomax (the subject of another Szwed biography), Smith salvaged history by making field recordings—though of a more idiosyncratic sort than Lomax’s, with subjects ranging from Ashkenazi rabbinical chants to Kiowa peyote songs to the moans of dying indigents in a New York City flophouse—and by collecting unremembered 78 rpm discs produced in the earliest days of the American recording industry. This would culminate in the issuing of Anthology of American Folk Music in 1952, a three-album collection whose influence is hard to overestimate. Its gnomic and otherworldly tracks reshaped the course of the folk-music revival and re-illuminated the careers of obscured musicians like the Carter Family, Blind Willie Johnson, Mississippi John Hurt, and others.

The Anthology is the source of Smith’s greatest renown, and the most mass market–friendly aspect of an otherwise inveterately underground personality. Given Szwed’s reputation as a biographer of figures like Lomax, Miles Davis, and Sun Ra, one of the welcome surprises of Cosmic Scholar is how the writer resists overly focusing on Smith’s musical activities, gamely traveling along with Smith on an exhilaratingly borderless journey through his investigations into the occult, Native Americana, folk art, and cinema. Early on, Szwed concedes that recounting the life of a notorious teller of tall tales may lead to unresolvable contradictions, but this only magnifies the kaleidoscopic multitudes Smith contained. The book thus becomes as much about the various demimondes and art worlds through which Smith circulated and the equally outré characters he met along the way, like some drug-addled Dorothy roaming through a countercultural Oz.

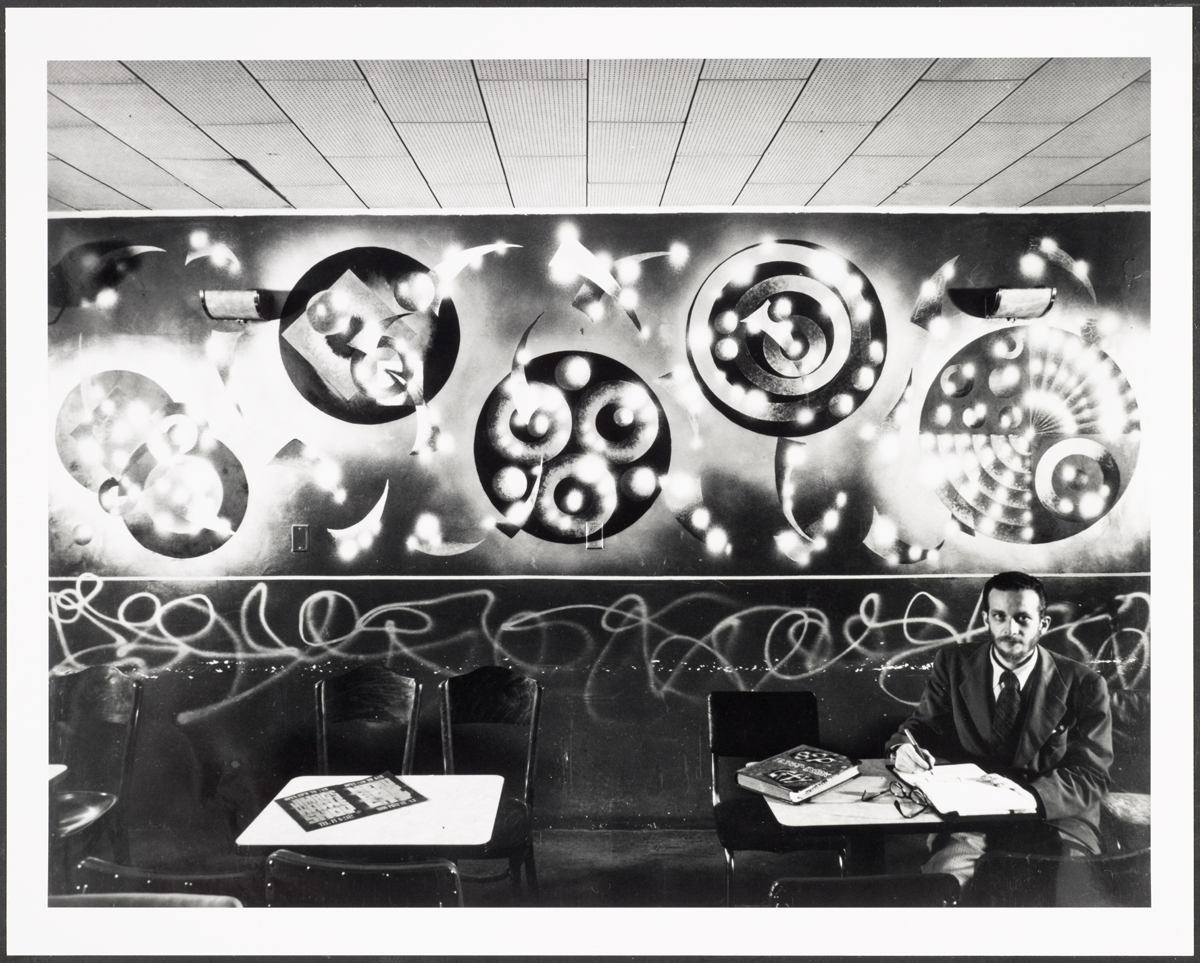

Harry Smith with his murals at Jimbo’s Bop City, San Francisco, ca. 1950. From Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith. Courtesy the Harry Smith Archives. Photo: Hy Hirsh.

Many first discover Smith through avant-garde cinema, as he has long been revered as one of the form’s greatest practitioners, an artist who revitalized the art of animation not once but twice, first with his early hand-painted films, later with his intricately choreographed cutout collages. P. Adams Sitney, Annette Michelson, Noël Carroll, and many other scholars have performed extensive hermeneutics on his cinematic output, which has proven to be as richly intertextual as anything by Joyce or Nabokov. Szwed largely avoids adding his own exegeses of Smith’s movies, more often quoting Sitney or Smith himself for description and explanation. The firsthand accounts of Smith’s at times charming, at times caustic personality—and the artist’s puckish, arcane prose—are strange and compelling enough on their own to require no further gloss, and indeed one of the dangers of Smith-delving is getting lost in the infinitude of details.

Harry Smith with his “brain drawings,” ca. 1950. From Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith. Courtesy the Harry Smith Archives. Photo: Hy Hirsh.

By emphasizing the completion and exhibition of his films as events in Smith’s life rather than fixed objects of study, Cosmic Scholar envisions its subject as not so much a filmmaker as a film performer, recounting the many devices and techniques Smith invented and incorporated into his shows: modified screens, glass slides, colored lights, improvised soundtracks—one time he even set fire to the projector. “Every audience saw a different film when Harry was there to perform,” Szwed notes. This is perhaps why Cosmic Scholar spends relatively little time on Smith’s painting, despite the fact he sometimes said it was his most important work; there are not so many colorful anecdotes that can spring from such a solitary endeavor.

Pulling back for a macroscopic view of Smith’s life allows Szwed to see him ultimately not as an artist or anthropologist but something grander: a visionary pattern-maker and pattern-seeker, unbounded by discipline, mesmerized by the internal intricacies of a wide spectrum of cultural activities. The author imagines Smith as a catalytic force who altered American culture as he moved through it. By focusing on the artist as a phenomenon, Cosmic Scholar favors the legend of the public Smith over any private self he may have hidden within the mass of artifacts and information that has survived and replaced him.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for cinema in all its forms in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.