Ed Halter

Ed Halter

In the HBO series, a Bacchus of the bong rip.

Ben Sinclair as the Guy in High Maintenance, season 4, episode 1. Photo: David Russell / HBO.

High Maintenance, season 4, created by Katja Blichfeld and

Ben Sinclair, HBO

• • •

In the opening of a recent episode of HBO’s High Maintenance, which concludes its fourth season tonight, the thirtysomething New Yorker in chunky earrings and statement jumpsuit yapping vocal-fried orders to her assistant as she steps into a ride-share probably reminds you of someone you’ve had the displeasure of interacting with before. “Omigod, I’m going to fucking kill Neka,” she mutters to herself, swiping through belfies on her phone as the driver stops for a second passenger.

She ignores her fellow rider until he quietly addresses her by name; their subsequent tension makes painfully clear that they are ex-friends, robbed of big-city anonymity by the bad luck of the algorithm. After an excruciating stretch of awkward non-interaction, she tries to break the ice by quoting what sounds like an old private joke about “a great big fat person,” but, remaining cool, he denies her a response. She stares out the window in the silence that follows, her slack face covered over by a stream of reflected lights. It’s as if an egotist from an Armando Iannucci comedy had stumbled into the wrong show, suddenly unable to function in an environment that isn’t predicated on some sadistic ping-ponging of awful people saying awful things to one another. Instead, High Maintenance offers the moment for the more humbling humor of empathetic self-recognition: Haven’t we all been here?

Ben Sinclair as the Guy in High Maintenance, season 4, episode 1. Photo: David Russell / HBO.

Such stochastic socializing and its side effects have long powered the narrative engines of High Maintenance. At the center of every episode are the peregrinations of the Guy, a nameless weed dealer who provides a connecting element between the myriad types composing his far-flung customer network—he’s played by Ben Sinclair, cocreator of the show with Katja Blichfeld. With his crooked grin, framed by an echt-Brooklyn weirdo-beard, the Guy could be the Spirit of Weed itself, a Bacchus of the bong rip. He bikes his case of goodies into the apartments of a menagerie of urban types: bodybuilders, lesbian moms, a depressed veterinarian, an indoor nudist, a cross-dressing husband; comedians, dancers, writers; an agoraphobe, an asexual, an ex-Hasid. The series is concerned not so much with marijuana itself as with the wide range of everyday city dwellers who crave its relaxing qualities. Each of the Guy’s customers serves as the viewer’s envoy into yet another self-contained micro-society, variously conglomerated around professions, passions, or family ties. The majority of characters appear for only one episode; a few move through different episodes not so much in storytelling arcs as Mandelbrotian loop-the-loops.

Larry Owens (right) as Arnold in High Maintenance, season 4, episode 1. Photo: David Russell / HBO.

The ex-friends mentioned above, for instance, go all the way back to High Maintenance’s pre-HBO roots in 2012, when Blichfeld and Sinclair’s project existed first as a “Vimeo exclusive” web series. In the episode titled “Olivia,” Max (Max Jenkins) and Lainey (Heléne Yorke) play a pair of cocaine-snorting sociopaths whose vile reputations precede them: when the Guy receives their call, their name pops up simply as “Assholes.” Like other exemplary internet “television” shows of the time—Issa Rae’s The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl, Adam Goldman’s The Outs—High Maintenance leveraged its online platform to play with the length and tempo of TV-style storytelling, often using just enough time to make its points. The entirety of “Olivia” runs under ten minutes—about the same length as the duo’s segment in the current season.

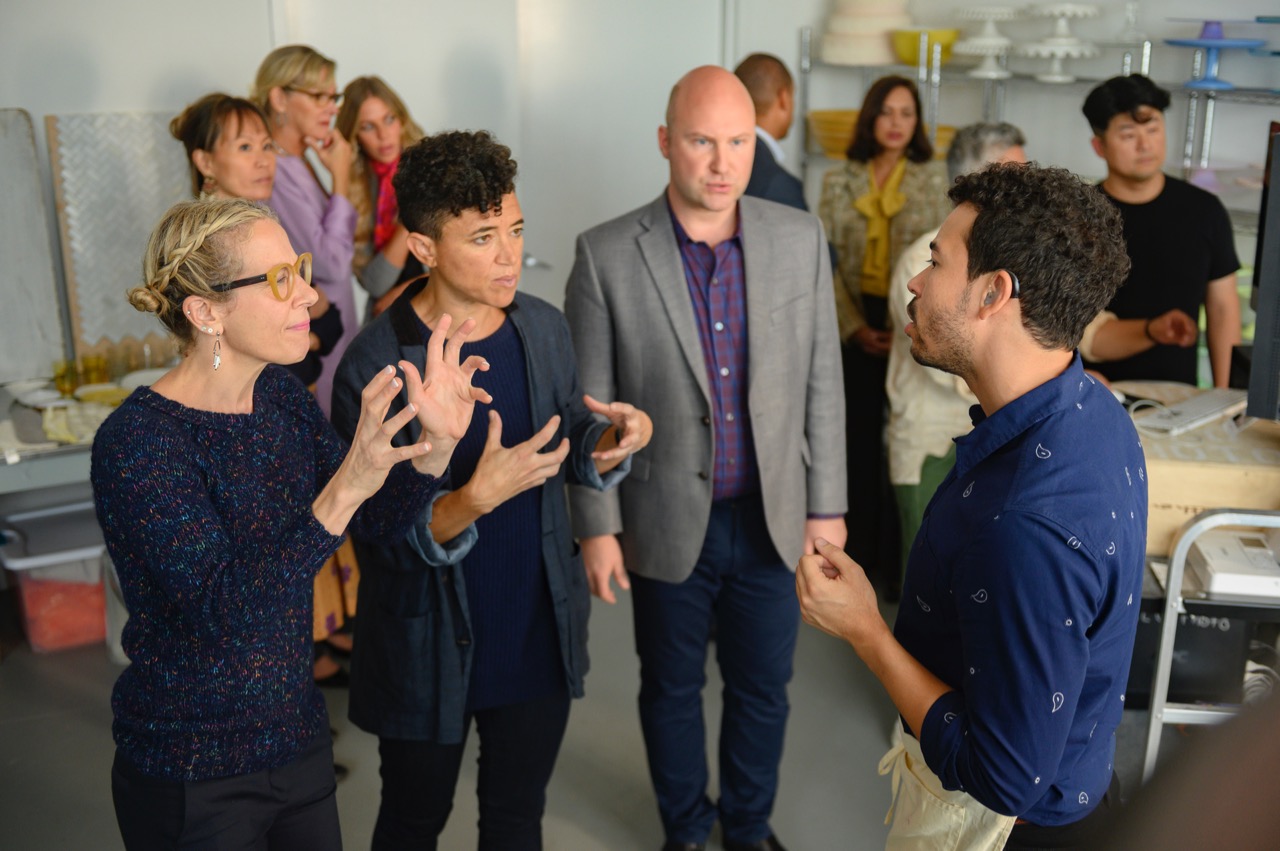

Mara Stephens as Jordan, Rami Margron as the photographer, Phillip Taratula as Jack, and Dickie Hearts as Alexi in High Maintenance, season 4, episode 7. Photo: David Russell / HBO.

“Olivia” is one of the funniest episodes from High Maintenance’s early era, filling its brief running time with relentless repartee between two of the most horribly selfish New Yorkers imaginable, and concludes with a non-redemptive gag. Yet it would prove atypical of the direction of the series as a whole, which has been more invested in quirk over cringe. Since its move to HBO in 2016 and its embrace of a more standard half-hour format, High Maintenance has become less about laugh-out-loud joke-making and more about delineating neatly sketched characters with distinct but relatable lives. In another season-four episode, an ASL interpreter (Mara Stephens) working on a Martha Stewart magazine photoshoot (for tasteful marijuana holiday cookies, naturally) encounters Stewart herself and, to the dismay of everyone on set, launches into a pitch for a nutritional supplement line she’s been hawking on the side. Stewart’s reaction is slightly displeased, but not especially cruel; the overriding emotion is not one of social discomfort but a sadness that the interpreter, whose stock in trade is the proper translation of affect and intent, remains so oblivious to her own blundering that she defeats her purpose.

Much like Stewart’s cannabis-infused entrepreneurialism, High Maintenance is nothing if not the product of a time when marijuana use has become mainstreamed to a degree in American culture almost unimaginable a decade ago, even in a state like New York, where the drug remains officially restricted. The classic stoner comedies, from the pioneering work of Cheech and Chong to later iterations like Friday or Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle, depended on a telltale whiff of semi-rebellious subcultural naughtiness that came with illegality. Weeds, the Jenji Kohan series that ran from 2005 to 2012, posed its single-mom protagonist as a reluctant drug dealer, drawn into a lucrative criminal operation due to financial hardship. In High Maintenance, cannabis plays about the same role as alcohol played in Cheers—as a premise for bringing disparate types together, if not under one roof, then through the latticework of one dealer’s client base.

Ben Sinclair as the Guy and Rachel Kaly as Ilana in High Maintenance, season 4, episode 9. Photo: David Russell / HBO.

High Maintenance is, like a good indica, soothing. The register it hits, expertly and consistently, is reminiscent of a very different program, The Great British Bake Off, which never fails to maintain a level of caring politeness, even when its judges critique the most catastrophic gâteau. Following trends in online culture and a greater shift in comedy itself, High Maintenance focuses on providing viewers with those little dopamine hits of recognition, seeing our own lives and experiences in comforting fictions. Perhaps this phantom link to another person’s life, even of an imagined sort, helps us feel a little bit less solitary in our own existence. The picture that High Maintenance gives us of ourselves is that we are all a little needy, all a little faulty. We’re fragile, failing creatures who, in the end, only have one other. The real question raised by the show is why we have been turning to comedy, and to television generally, for this form of reassurance and self-medication.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His collection From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, coedited with Barney Rosset, was published in 2018 by Seven Stories Press.