Jennifer Kabat

Jennifer Kabat

Of blooms and biases: a show on early modern plant-medicine books dodges issues of capitalism and colonization.

Seeds of Knowledge: Early Modern Illustrated Herbals, installation view. Courtesy the Morgan Library & Museum.

Seeds of Knowledge: Early Modern Illustrated Herbals, curated by John McQuillen, Morgan Library & Museum, 225 Madison Avenue, New York City, through January 14, 2024

• • •

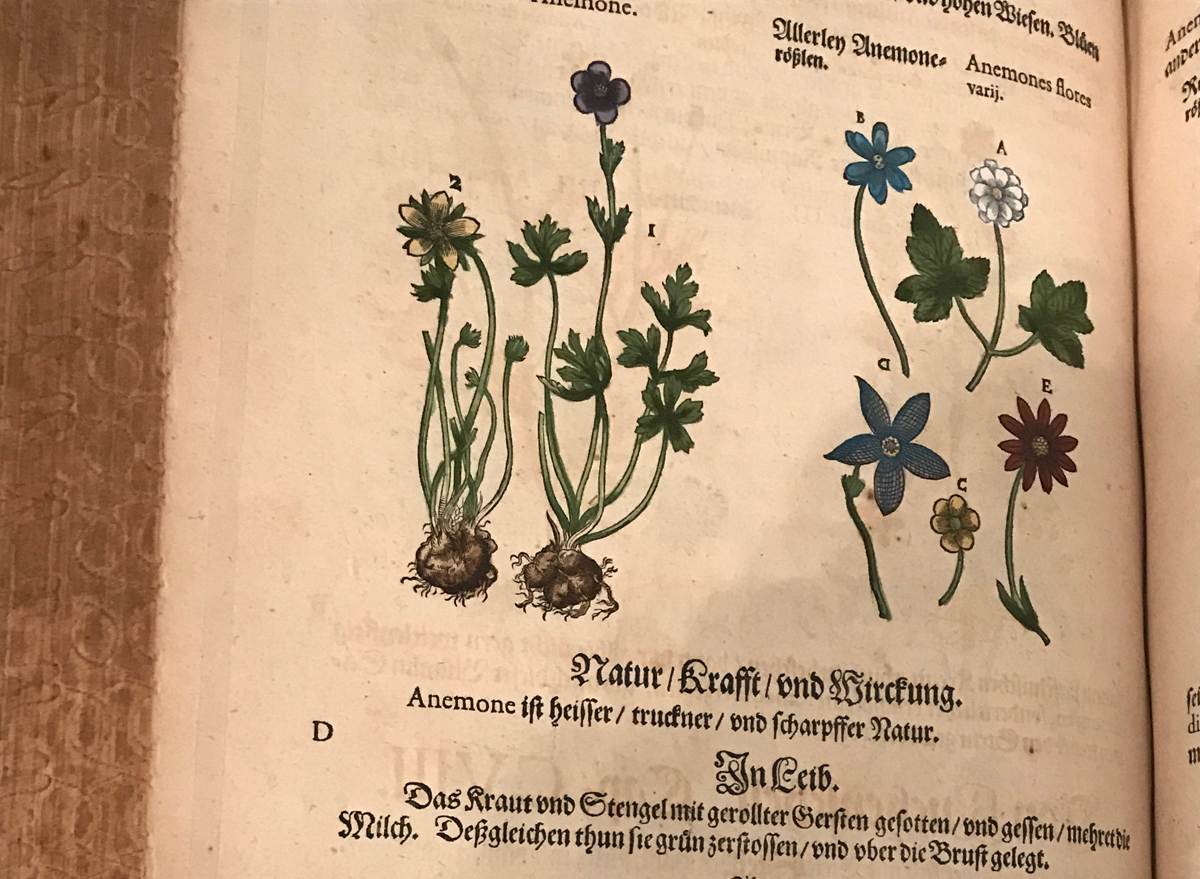

It is the blue that gets me—cerulean so rich it takes my breath away. The color only appears on two tiny flowers, anemones. In them I see Pecola in Toni Morrison’s debut, longing for a white girl’s eyes. It is this blue of pain that comes to me through the centuries in the Morgan Library’s Seeds of Knowledge. The exhibition is dedicated to early modern herbals, guidebooks that in their time were bestsellers. Marketed to physicians and a burgeoning lay audience, they cataloged what today we’d call plant medicine. I study the volumes under the discreet museum lighting, and those eyes—these flowers—wink at me. I take a picture to hold the color; still, it slips away.

Seeds of Knowledge: Early Modern Illustrated Herbals, installation view. Courtesy the Morgan Library & Museum.

The exhibition is small, and the gallery claustrophobic. You might call it a jewel-box of a show. The room glows with the title wall’s gold lettering, but the space is dark and the subject even darker. (I see it as a symptom of the rise of white male power, as the herbals help usher in the modern era.) The almost two-dozen books on view are largely culled from one rich man’s library, now displayed in a dead rich man’s library. An exhibition assembled from a single source like this begs questions of bias and financial return. One entire wall is given to a video of the collector, Peter Goop. He fondles the pages of his centuries-old books and runs his hands over the rosemary plants in his garden, releasing the oils that, I know, help memory.

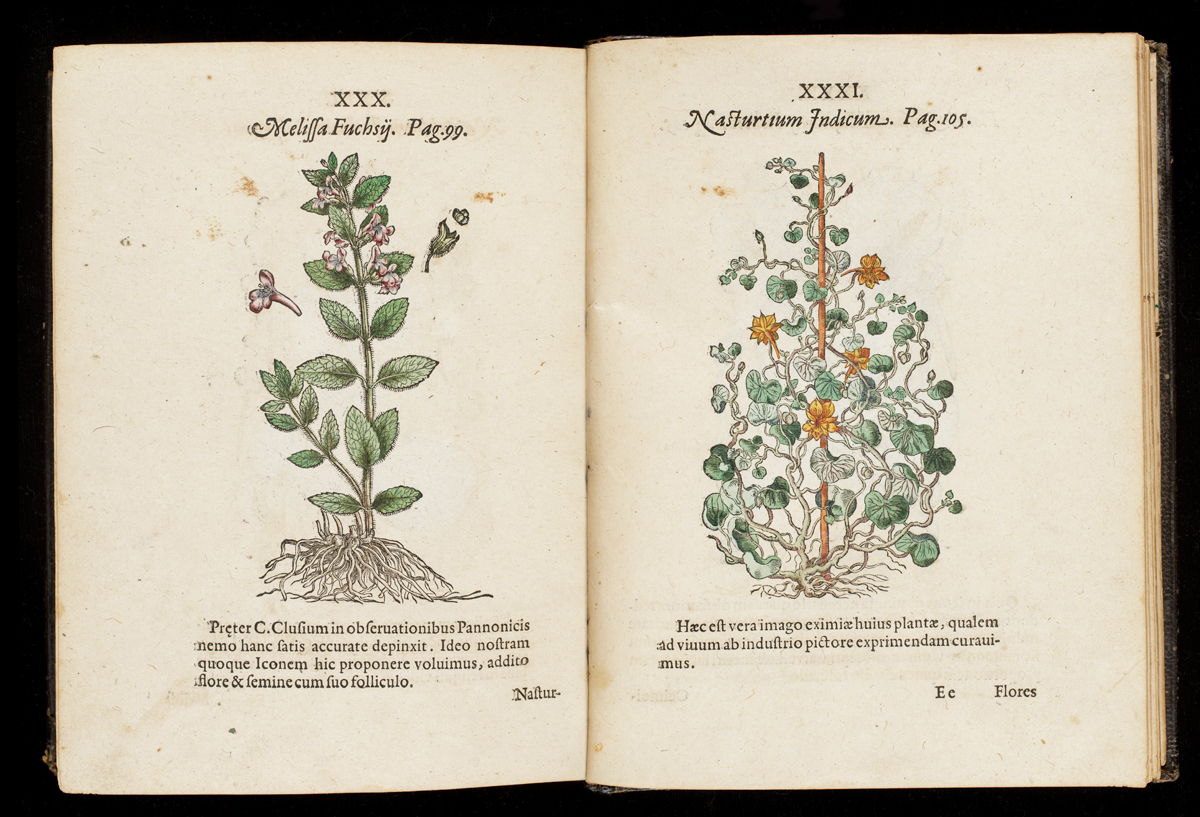

Joachim Camerarius the Younger and illustrator Jost Amman, Hortus medicus et philosophicus (Medical and philosophical garden), 1588. Courtesy Peter Goop Collection. Photo: Naomi Wenger.

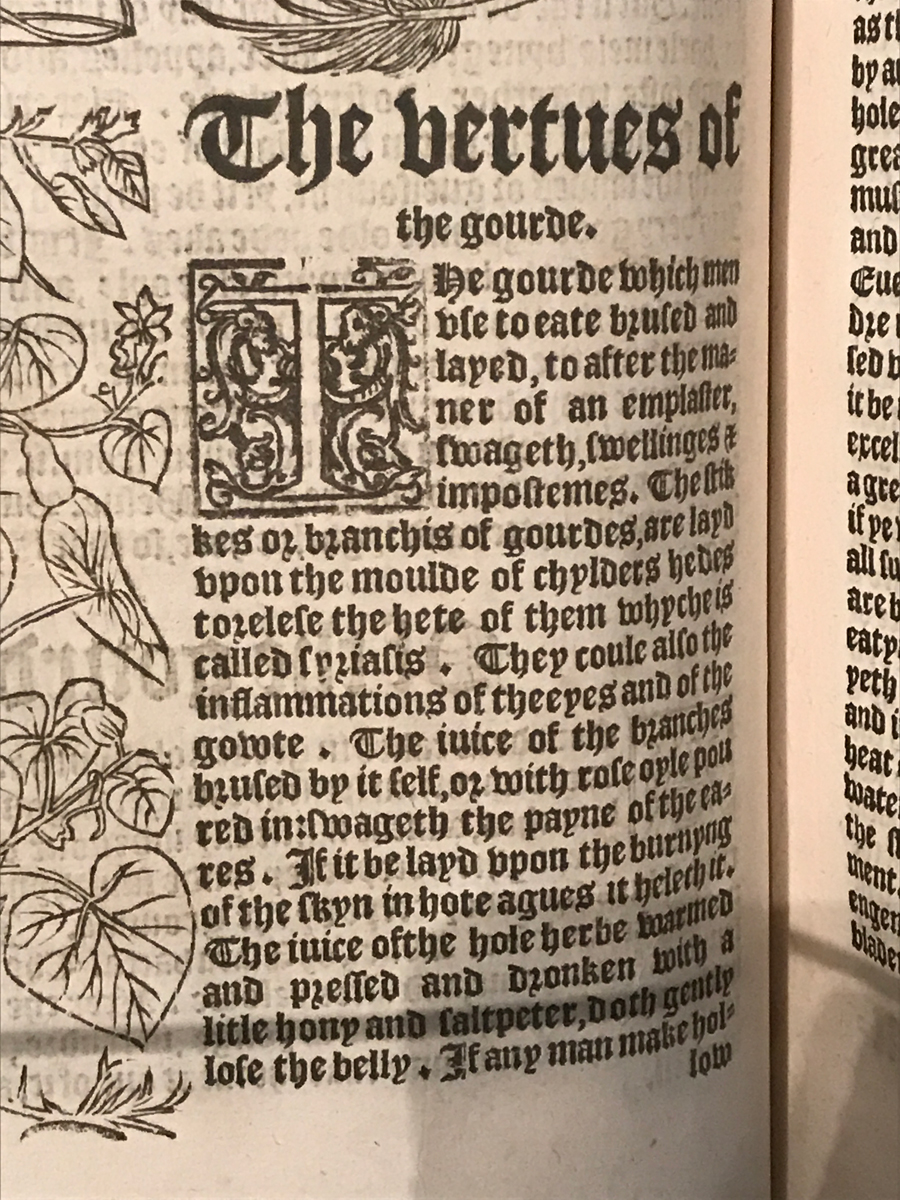

I come because I want to see what the books might tell me, only they are mute, hidden behind glass, with no translation offered for their Latin, German, and French texts. An illustration of bugloss, almost five hundred years old, glows on a touch screen. The flower is a “weed” that grows in waste places (and on my road). In 1597, John Gerard wrote of bugloss (though his The Herball is not here), that it is “of force and vertue to drive away sorrow and pensiveness of the minde, and to comfort and strengthen the heart.” A recent study says that bugloss indeed does work as an antidepressant. One book, open to a detailed 1588 print, identifies lemon balm (also good for anxiety) by its Latin name, Melissa. Two of its flowers mysteriously levitate off the plant, like an alien abduction, but I cannot turn to “Pag. 99” as the image instructs. Trying to untangle “the Vertues of the gourde” in William Turner’s 1551 A New Herball, laid out inside one of the room’s vitrines, I manage to decipher: “They coule also the inflammations of the eyes and of the gowte.”

William Turner, A New Herball, 1551 (detail). Photo: Jennifer Kabat.

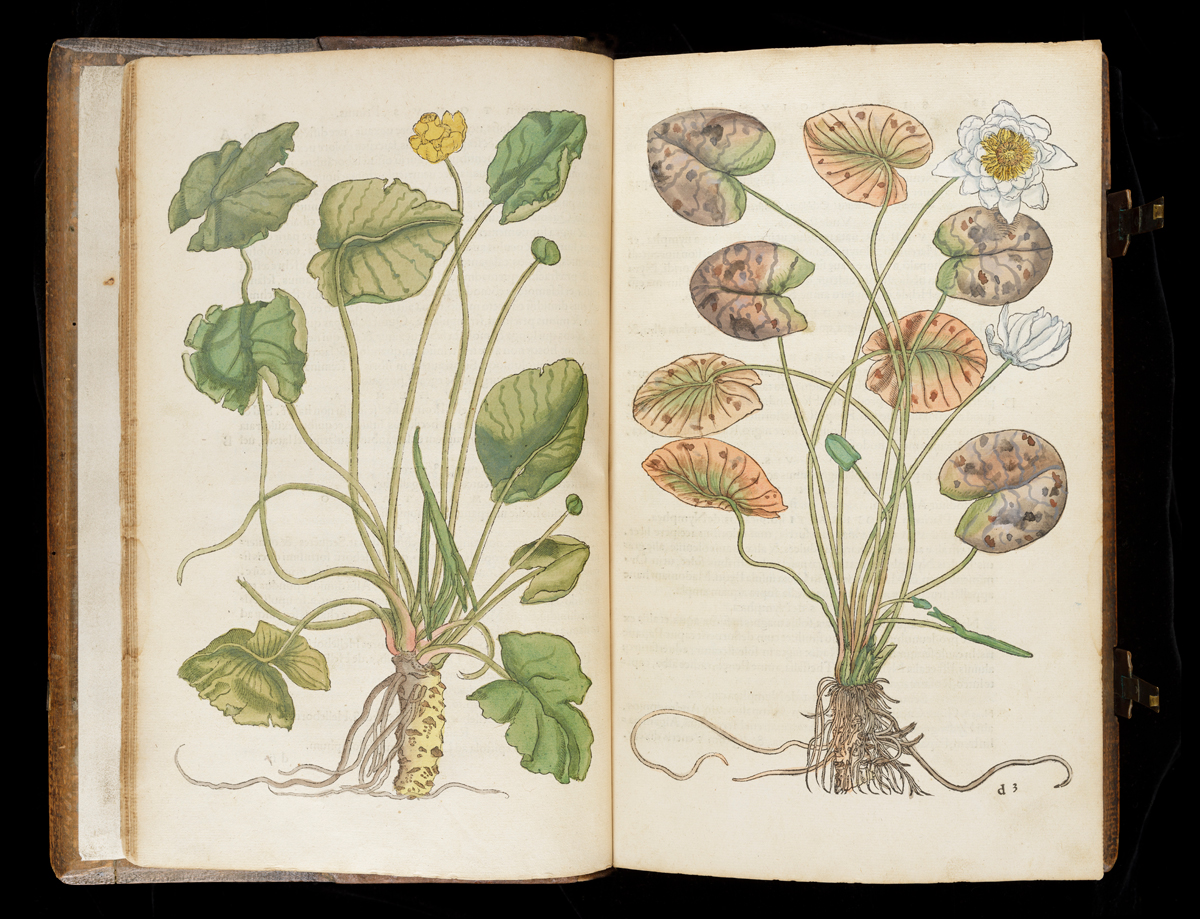

Then, there are the actual plants squashed and flattened into another book, called the Herbarium Vivum, meaning living, but oh so dead. Or, the life-size images of tulips spread across a centerfold—roots, bulbs, blooms and all—in the Hortus Eystettensis (Garden of Eichstätt). The flowers are new to Europe (also new: copperplate printing, which allows such exquisite detail). It is 1613, two decades before the tulip bubble that will become a metaphor for capitalism.

Basilius Besler and engraver Johann Leypold, Hortus Eystettensis (Garden of Eichstätt), 1613. Courtesy Peter Goop Collection. Photo: Naomi Wenger.

Seeds of Knowledge is set between 1480 and the year the lavish tulips are published. These herbals take in the era from Columbus to ships carrying the first enslaved peoples to Virginia in 1619. That the books appear at the cusp of capitalism, conquering, and colonization could easily be the show’s subtext—but is never in the gallery’s texts. The guides also come thirty years after Gutenberg’s revolution in movable type, fueling the Protestant Reformation by giving people a direct relationship to God through reading the Bible in their own language. (This, too, is unaddressed in the wall labels—strange, given the Morgan owns four Gutenberg Bibles.)

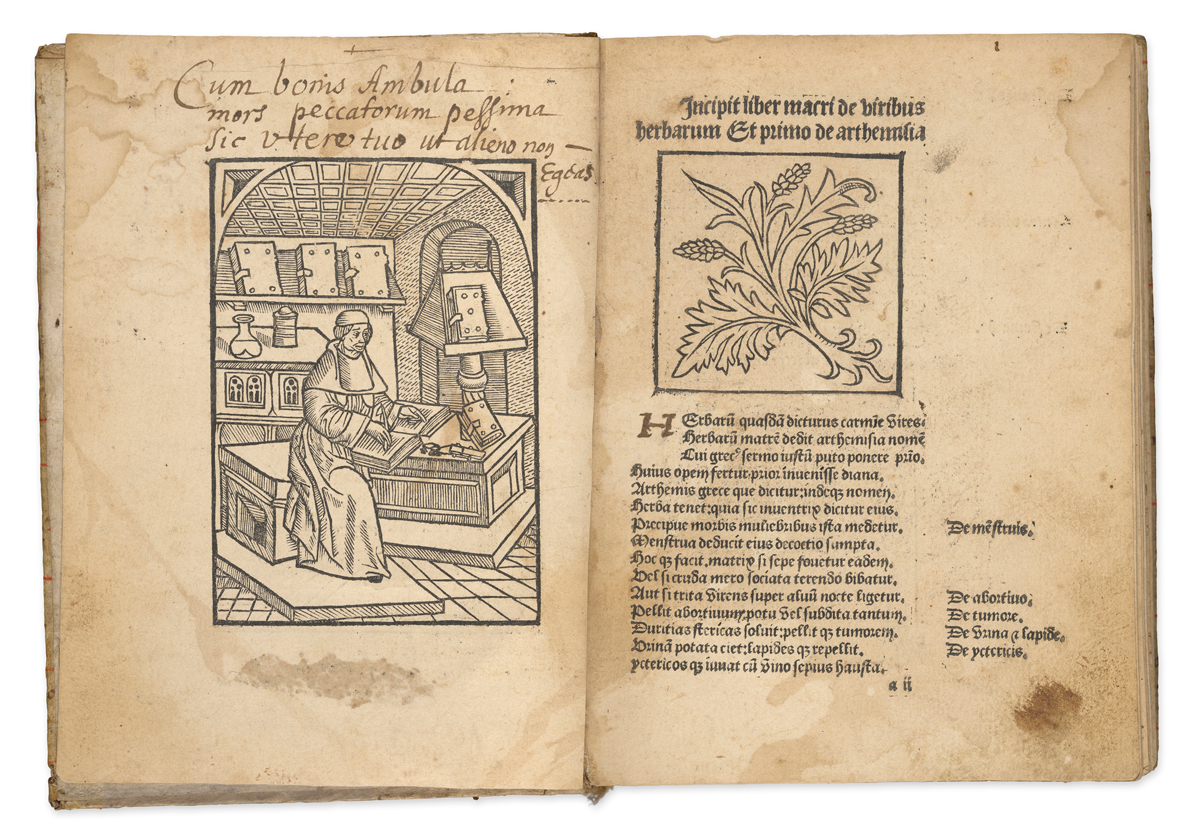

Odo of Meung [pseud. Macer Floridus], De viribus herbarum carmen (Poem on the powers of herbs), ca. 1495. Courtesy Peter Goop Collection. Photo: Naomi Wenger.

By the mid-1500s, herbals start to lionize individual over collective knowledge. In his 1543 New Kreüterbůch, Leonhart Fuchs (a Lutheran) includes portraits of himself and his artists, dressed as doctors. Fuchs holds a plant (the direct relationship to God now becomes the direct observation of nature). The portrait asserts authorship, advertising his book’s superiority, being based on his sole research. In scholarship, he’s commonly called the “father of German botany.” There are other such fathers in the show, while the field of botany, too, espouses a kind of individualism, isolating plants from ecosystems. The discipline becomes a model for Western science, and herbals become part of codifying medicine and organizing it into a male profession.

The largest producer of herbals was Reformation Germany. More women were also executed there as witches than anywhere else in Europe, just as these books collect women’s oral knowledge, amassing folk cures and herbal remedies women passed down as healers and midwives. Those facts are not separate. Or, they shouldn’t be. They’re also never broached (outside the hundred-dollar catalog). Nor is colonization, not really.

Seeds of Knowledge: Early Modern Illustrated Herbals, installation view. Courtesy the Morgan Library & Museum.

Flicking through the touch-screen display, a page of luminous tomatoes appears, but nothing saying that these are new to Europe or even that they came from the Americas. The only reference to colonization is in a label for the Herbarium Vivum, which explains the tome includes tobacco and tomatoes, and that there was eager trade in tomato seeds between European botanists. Meanwhile, Fuchs, in the herbal with his portrait, was the first to publish maize in Europe, though the Morgan doesn’t tell us—or include a print of the grain.

In the atrium just outside the gallery is a “Living Land Acknowledgement,” living because the Morgan believes Indigenous New York, Lenapehoking, continues into this moment. The text promises to “confront this legacy” of settler colonialism and “honor Indigenous voices.” Here was the institution’s chance. We have maize; we have plants brought back to Europe, objects of collecting, objects of harm. We have this moment of peoples and plants both being subjugated.

Otto Brunfels and illustrator Hans Weiditz the Younger, Herbarum vivae eicones (Living images of herbs), 1531. Courtesy the Morgan Library & Museum.

Reading the acknowledgment, I dream of a counternarrative: men sail to America (it is never called that, the original Indigenous terms remain) and bring back home a new philosophy. The Europeans meet the Lenape, who are matrilineal and live collectively. Henry Hudson travels up a river that never gets his name. The Haudenosaunee instruct him in the world’s first consensus democracy, which they created in the twelfth century. He broadcasts this good news from the “new world,” including a vision of botany where we and plants are intertwined. Instead of domination, it’s a realm of radical equality, where plants are our teachers.

In a time when our power to control our bodies is ever more in doubt, plants offer possibility. They help regulate our hormones and even provide something like a morning-after pill. Which makes plants seem like allies against the current regime of white male power. To breathe is to be plant; our air comes from plants. They feel pain and communicate, and have evolved to be bisexual and asexual and with multiple other sexualities. What if these explorers had returned to Europe with new ways of being multiple in the world? I could say it’s not too late to learn. And, I can only hope.

Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Joachim Camerarius the Younger, and Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbos, Kreutterbuch (Herbal), 1586 (detail). Photo: Jennifer Kabat.

What I’m left with, though, in the Morgan, is the longing, the blue. . . . How has its brilliance survived all these centuries? Is it lapis ground from stone in Afghanistan? Or indigo, the plant brought by Marco Polo to Europe? Anemone was the daughter of the god of the winds; her plants grow near my house. Tiny white flowers, not blue, appear in early spring. Called ephemerals, the blooms are here and gone, and I tincture their roots. These anemones—wood anemones—are good for pain, existential pain.

Jennifer Kabat’s books The Eighth Moon and Nightshining will be published by Milkweed Editions in spring 2024 and 2025. Her writing has been in Best American Essays, Granta, BOMB, Harper’s, and McSweeney’s. She lives in rural upstate New York and serves on her volunteer fire department.