Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

Self-abnegation, self-cancellation, self-criticality: a new survey of the conceptualist’s work exhibits the art of erasure.

Christine Kozlov, installation view. Courtesy American Academy of Arts and Letters. Photo: Charles Benton. © Christine Kozlov Estate. Pictured, left foreground: A Mostly Painting (Red), 1969.

Christine Kozlov, American Academy of Arts and Letters, organized by Rhea Anastas and Nora Schultz, Audubon Terrace on Broadway between West One Hundred Fifty-Fifth and One Hundred Fifty-Sixth Streets, New York City, through February 9, 2025

• • •

There’s a painting in Christine Kozlov, the survey of the late conceptualist’s work at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, that looks straightforward but isn’t. Just bigger than a letter-size sheet of paper turned on its side, the picture spells out A MOSTLY RED PAINTING in capital sans-serif letters. The white words appear on a dark gray ground; there is no red chroma in it at all. The painting, executed in 1969, made me think of the language games that Jasper Johns set up a decade earlier in False Start (1959), a canvas featuring patches of colors and the words for those colors, which both match and mismatch, collide and diverge. Johns showed how two kinds of intelligibility compete—there’s what we see and what we read—and Kozlov brings the distinction to a head by prying the two apart and then pitting them against each other. But the funny part of the painting is the red (or lack thereof), which raises the question of sound. Red is a homonym for read, and this is a mostly read painting, but the mostly is important: there is still some other way—just barely—to experience the work as well.

Red, of course, is more than just a color; it’s also a politics. Kozlov’s is not red as in roses but rather Mao’s little red book. Red as in revolution—and Kozlov’s time was the moment for it—but the painting’s politics are mostly, not entirely, red. It’s a painting, after all, still bourgeois enough to hang in a living room, even if painting occupied an anomalous place in Kozlov’s career. The artist titled the work A Mostly Painting (Red), and it is one of only two canvases in the exhibition. Both are small, nondescript, self-effacing objects, more like exit signs than color fields. As is the case with much conceptual art, the rest of the exhibition takes a hard turn away from tradition. Most works are telegrams and prints; photographs and publications; sound recording devices and canisters of unprojected film. Vitrines display, among other items, the printed matter produced over the course of the artist’s brief career, items hovering between working notes, documentation, and finished works of art. Much of this can be almost entirely read; there is often little to see after scanning the text.

Christine Kozlov, installation view. Courtesy American Academy of Arts and Letters. Photo: Charles Benton. © Christine Kozlov Estate.

Kozlov made the majority of these pieces in the mid-1960s through the late 1970s, when she lived in New York. In 1967, she started the Museum of Normal Art with Joseph Kosuth, where they staged an exhibition of “non-anthropomorphic art” and later invited fifteen artists to display their favorite books. In the space’s first exhibition, Normal Art, Kozlov displayed a canister of blank film; negation, rejection, and withholding would serve as her key terms. This abnegating tendency reached a high point with 271 Blank Sheets of Paper Corresponding to 271 Days of Concepts Rejected (1968). I’ve always wondered which came first, the concepts or the idea to reject them—the decision to make something out of cancellation. Did her ideas ever stand a chance? Self-criticality and self-doubt wrestle throughout Kozlov’s practice. Perhaps this was endemic to conceptualism—once art had been reduced to its minimal condition, was there any point in still keeping on?—but one also imagines that Kozlov had some ambivalence about participating in an artistic field that was oftentimes an extremely verbose boys’ club.

Feminism was central for Kozlov, but her critique appears in sly ways. It’s there in the exhibition’s other painting, Untitled (After Goya) (1968), which also employs text, spelling out LAS MAJAS on a light charcoal ground. The Spanish painter Francisco Goya created two depictions of la maja—La maja vestida and La maja desnuda—one clothed the other naked, both splayed out on a divan. A couple hundred years later, Kozlov reunited them and removed the visual pleasure. This might be her clearest assault on art history, but there are other political interventions, too: a would-be manifesto on “tokenism” in the art world tucked into a vitrine and an undated work, Untitled (Social Structure of Bees), that describes the insect’s sexual dynamics in pointed fashion. Here, text is housed in a hivelike structure, and while we can read some of this treatise, most is struck through. It’s hard not to see this cancellation as an allegory for Kozlov’s own self-erasure. Though she passed away in 2005, the artist produced little work after the 1970s. (A lone vitrine gathers papers from 1991 relating to a project on the first Gulf War.) One wonders what happened—and what might have happened.

Christine Kozlov, installation view. Courtesy American Academy of Arts and Letters. Photo: Charles Benton. © Christine Kozlov Estate. Pictured: Information: No Theory, 1970.

The mode of presentation here—the exhibition was organized by independent curator Rhea Anastas and artist Nora Schulz—is in the high austere style. The wall-hung work, aside from the paintings, is all housed in the same slim aluminum frame; there’s not a scrap of interpretive text to be found anywhere on the walls. My memory of the show is that of a large unadulterated chunk of white cube—that rich feeling of a grand building scrubbed clean. This is the kind of hang that lets the art speak for itself (as people used to say), or lets it breathe, but the problem is that Kozlov’s work seems very ambivalent about speaking and breathing. It’s hermetic and cryptic, turned in on itself, constantly canceling itself. Sometimes the emptiness of the galleries seems to the point, as is the case with Information: No Theory (1970), a recording system that commits a room’s sound to magnetic tape only to immediately erase it. In this case, the great volume of air seemed charged and activated, but often I felt that the elegant airiness operated like a buffer and that the work could use some coaxing, that some itinerary or timeline or thematic might have been laid out.

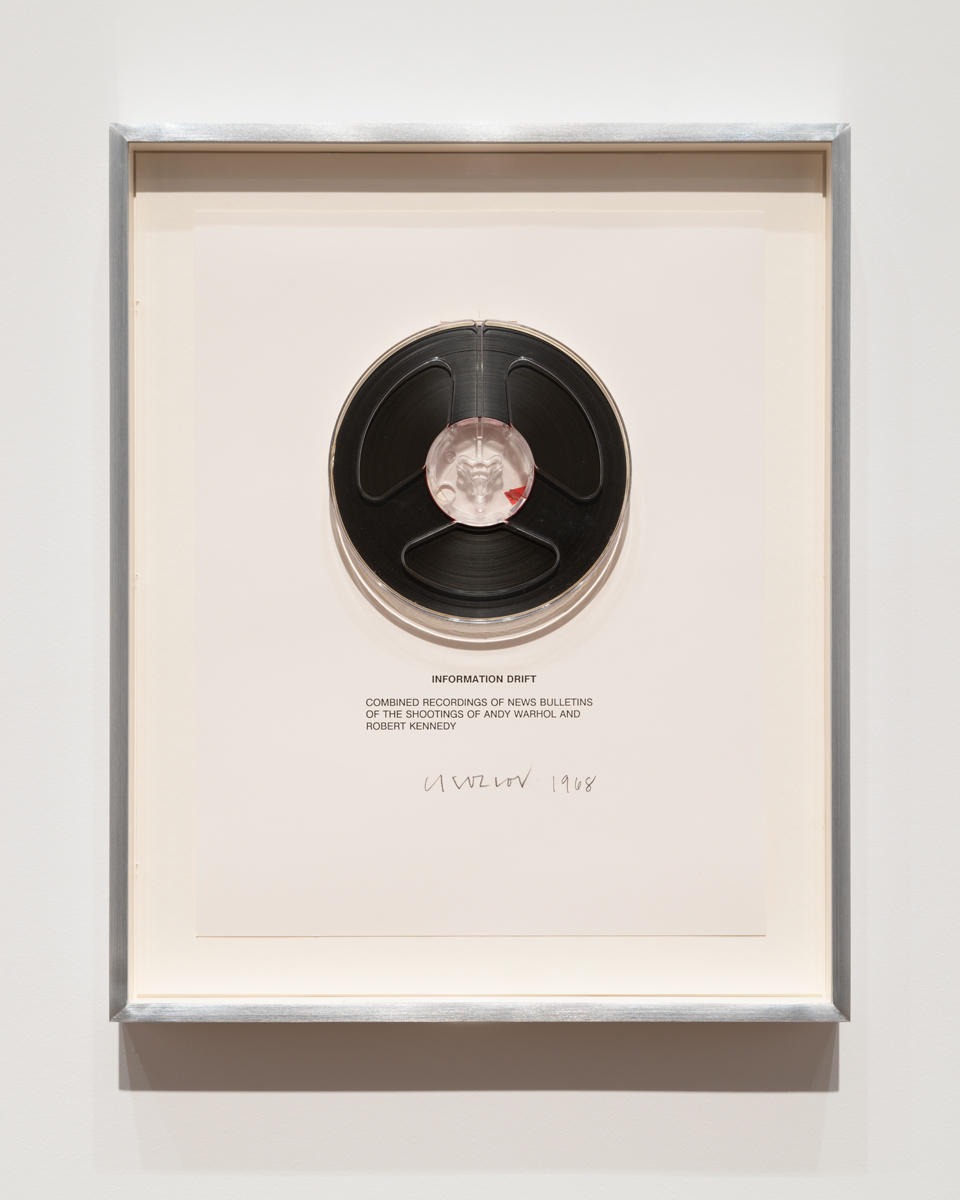

Christine Kozlov, installation view. Courtesy American Academy of Arts and Letters. Photo: Charles Benton. © Christine Kozlov Estate. Pictured: Information Drift, 1968.

For instance, sound—and the absence of sound—is a through line in Kozlov’s practice. Information Drift (1968), a framed reel of magnetic tape, contains news broadcasts about the shootings of Robert F. Kennedy and Andy Warhol that year. Warhol was an avid recorder, and the work is a fitting homage to the artist, but Kozlov’s decision to withhold access also serves as a pointed allegory about the inaccessibility of history. There is a difference, though, between something being inaccessible and choosing not to investigate it, and much of the work here feels unexamined. The exhibition brochure suggests that artwork is more contemporary when unframed by discourse, and that context and history somehow aren’t particularly feminist. We are told the curators thus decided to engage the work directly, and yet the brochure does not offer a word of interpretation about what any of it might mean. In a sense, the curators have taken Kozlov’s method of self-abnegation as their own. The result is something like a double negative. While it doesn’t make a positive, Christine Kozlov is intriguing. One wants to learn more; but I imagine the work will continue to operate as a well-guarded secret.

Alex Kitnick teaches art history at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.