Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick

Living in a material world: artworks in an MIT exhibition teem with

the nonhuman.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured, center foreground: Jes Fan, Systems II, 2018. Composite resin, glass, melanin, estradiol, Depo-Testosterone, silicone, wood, 52 × 25 × 20 inches. Pictured, back left corner against right wall: Nour Mobarak, Sphere Study 4 (Dilettante Politic), 2020, trametes versicolor, wood; Sphere Study 3 (Failed Sphere), 2020, vinyl, trametes versicolor, wood. Pictured, left side of window on right wall: Miriam Simun, The Sound of a Hive Giving Birth, 2022. Beeswax, lemongrass essential oil, Sichuan honey, pyrus pyrifolia (Ya Li pear) pollen, dried pyrus pyrifolia (Cangxi Snow pear) flowers, dried pyrus calleryana (Bradbury pear) flowers, dried pyrus communis (Green Anjou) pears, acrylic, 24 × 24 × 1 1/4 inches.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, curated by Caroline A. Jones, Natalie Bell, and Selby Nimrod, with research assistance by Krista Alba, MIT List Visual Arts Center, 20 Ames Street, Building E15–109, Cambridge, MA, through February 26, 2023

• • •

Mushrooms are having a moment. A new coffee-table book titled The Future is Fungi: How Fungi Feed Us, Heal Us, and Save Our World (2022) seems to sum up the salvific sentiment. If mushrooms once connoted psychedelia, they now promise new life, offering a way out of our end-times malaise because (1) they will be here after us, or so the scientists say, and (2) they will optimize our last days (or so the nutritionists claim) by offering tension relief, good digestion, and brain health. Now they have their own exhibition, too.

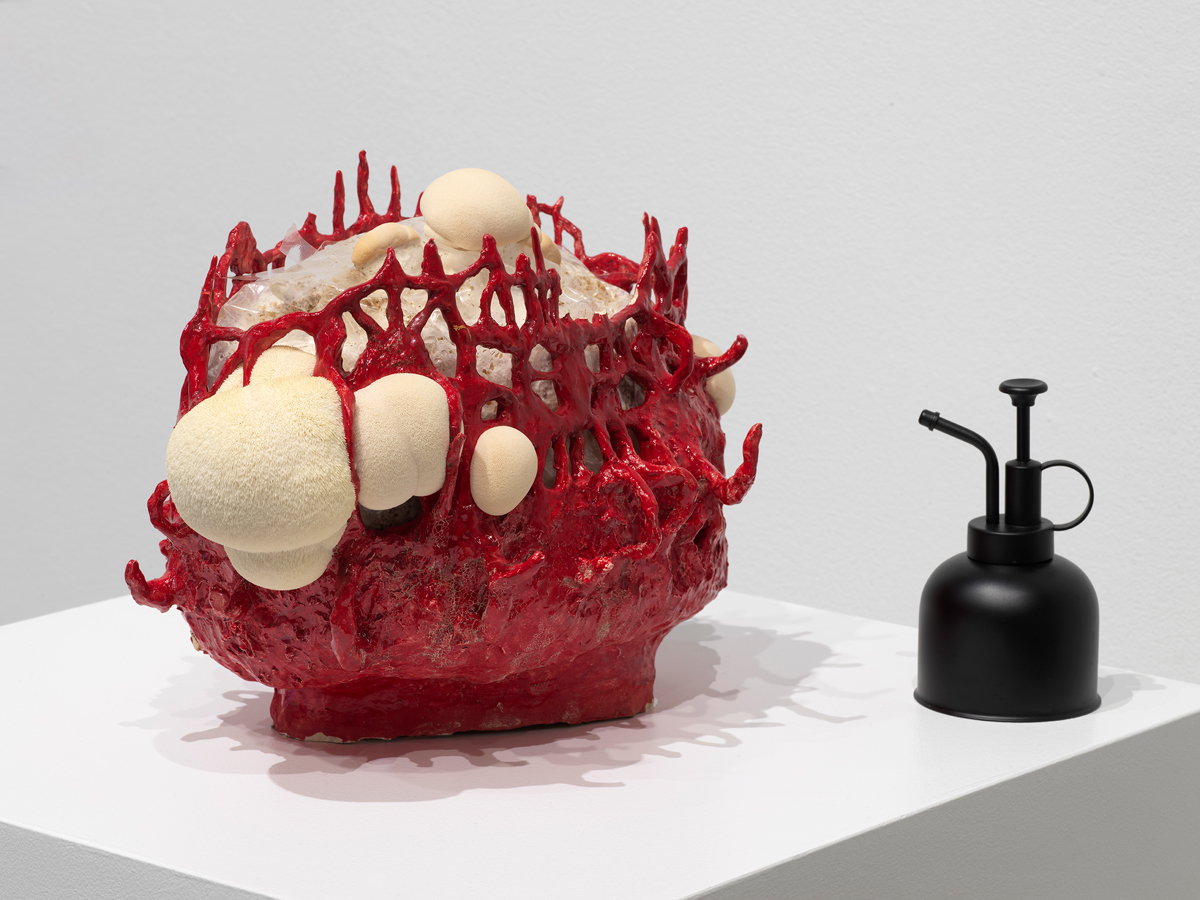

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Candice Lin, Memory (Study #2), 2016.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, curated by Caroline A. Jones, Natalie Bell, and Selby Nimrod, is not explicitly about mushrooms, but they’re all over the galleries—perhaps because the subject of the biosphere (“the regions of the surface, atmosphere, and hydrosphere of the earth . . . occupied by living organisms”) is so large that it needs something concrete to hang on. And importantly, when I say mushrooms, I don’t mean paintings of mushrooms, à la Yayoi Kusama, or sculptures of mushrooms, à la Carsten Höller, but actual fungi sporing and swelling in real time. Candice Lin’s work, for example, offers a red ceramic net of lion’s mane, occasionally spritzed with urine, while Nour Mobarak’s objects comprise specimens of turkey tail atop deflating beach balls. Such mycelial realness is key to the show: Symbionts is less a contemplative space for viewers than a bounded ecology for creatures. Artworks here lead lives of their own, and, in some cases, quite literally. For his contribution Pierre Huyghe simply released cellar spiders into a side gallery. Spiders change a viewer’s relationship to art. One doesn’t so much look at them as inhabit space with them, and though I don’t recommend trying to squash them, doing so would only draw the visitor more closely into the installation’s web. This symbiotic relationship (you and me and the spider are all symbionts) is a key part of this suggestive exhibition’s point.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Pierre Huyghe, Spider, 2011. Spiders in corner of the wall, dimensions variable.

Perhaps because Symbionts is housed at an institute of technology—upstairs there is a center dedicated to the study of “future children” as well as the MasterCard Future of Transactions Laboratory—it can’t avoid a certain wow factor. Some works look like product displays for upscale aquarium stores while others might be props for a new Cronenberg film—a command center to control the world’s nervous system. But many offerings, while seemingly organic, are essentially inscrutable—one must read the object labels to learn about the funky things inside: a medley of pears, beeswax, and Sichuan honey; a mélange of dung and breastmilk; a potion of testosterone, estrogen, and melanin. As startling as these substances are, their recondite nature leads to a strict divide between the material-organic and intellectual-conceptual. These things will rot and reorganize themselves regardless of whether the viewer knows it, but we won’t know what they are, and what they are doing, unless additional information is conveyed. In other words, the materials—or at least their meanings—are largely invisible without curatorial armature. The wall texts thus function somewhat like the lists of ingredients on high-end juices, a fact that artist Josh Kline punned on successfully in his refrigerator-apparatus Skittles, installed on New York’s tourist-mobbed High Line in 2014. Kline, who has a retrospective opening at the Whitney Museum of American Art this coming spring, is missing here, and Symbionts, too, for all that it contains, occasionally feels somewhat pious in regards to its subject.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured, left to right: Jenna Sutela, Gut Flora (Cerebrobacillus), 2022; Gut Flora (Lactogalaxius), 2022; Gut Flora (Glossococcus), 2022. Fired mammalian dung glazed in breastmilk, 35 3/8 × 23 5/8 inches each.

About a decade ago many people interested in contemporary art and philosophy obsessed over new materialisms and object-oriented ontology. People loved to say OOO; “vibrant matter” was the order of the day; I even taught a class on the stuff. Under this new regime the human wasn’t so much decentered, as it was in deconstruction, but rendered simply another organism in an ecosystem not particularly concerned with it. (The gallery guide for Symbionts echoes this proposition by noting that “the majority of genetic materials in the ‘human’ body are not actually human.”) Then, a few years later, history erupted, and discussions of human life—and particularly Black life—called the disciplines back from the brink. While nature clearly remains a pressing concern in our era of climate catastrophe, our collective project is now to discuss how power and identity manifest themselves in a world made in large part by human actors, structures, and institutions, as if such things had ever gone away.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured, foreground: Crystal Z Campbell, Portrait of a Woman I and Portrait of a Woman II, 2013. Upcycled wood, MDF, custom 3D laser-cut solid glass cubes of HeLa cells (image of HeLa cells made with Dr. C. Backendorf and G. Lamers) and of Henrietta Lacks, 35 × 6 × 6 inches each.

Occasionally Symbionts provides ideas as to how these two strands of thought might come together. Crystal Z Campbell’s Portrait of a Woman I and II (2013), for example, offer 3D etchings of cancerous cells belonging to Henrietta Lacks atop wooden pedestals in a darkened gallery. These surreptitiously sourced specimens facilitated science and dehumanized its subject at once, turning Lacks, a Black woman, into a test case without her knowledge. Horrific as this story is, it subtly pushes against the exhibition’s thesis, which seems to argue for the primacy of the nonhuman (emblematized by the incessant growth of algae and fungi, and the intelligent networks they create) over the ethical decisions of human agents. Though there are mushrooms aplenty here, humans are in short supply.

Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Claire Pentecost, soil-erg, 2012 (detail). Graphite and compost drawings on 100 percent rag paper, two tables with glass panels and gold-leaf varnish, twenty soil ingots.

One of the most persuasive pieces in Symbionts offers a counterpoint to this anti-humanist line, and it is one of the first the visitor sees: a series of drawings by Claire Pentecost, which, as works on paper that employ traditional techniques of draftsmanship, are, on first glance, some of the more conventional offerings in the show. The drawings are prototypes for a utopian system of currency, which would circulate according to different principles than those that organize national coinage, precisely because they have a different backing; they rely on the earth’s energy rather than a financialized bank. Titled soil-erg and first displayed at documenta 13 in 2012, where it was similarly surrounded with gold bar–style ingots of humus, Pentecost’s installation proposes a system of value and exchange in which humans and nature are not reduced to equal inhabitants of the biosphere but rather retain their own defining characteristics. Here we have different kinds of actors involved in a complex yet genuinely reciprocal relationship. Fittingly, the faces on these bills range from those of squirrels and bees to artist Ana Mendieta and Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau. Though teetering on the edge of twee, soil-erg makes it exciting to think about how we might engage the world with the multiple faculties at our disposal. If there is to be a future, after all, it will necessarily be a wild experiment of lending and borrowing, of give and take.

Alex Kitnick is Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Culture at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.