Svetlana Kitto

Svetlana Kitto

A Whitney exhibition of photography, collage, performance, and multimedia installation revolves around themes of queer community, loss, and celebration.

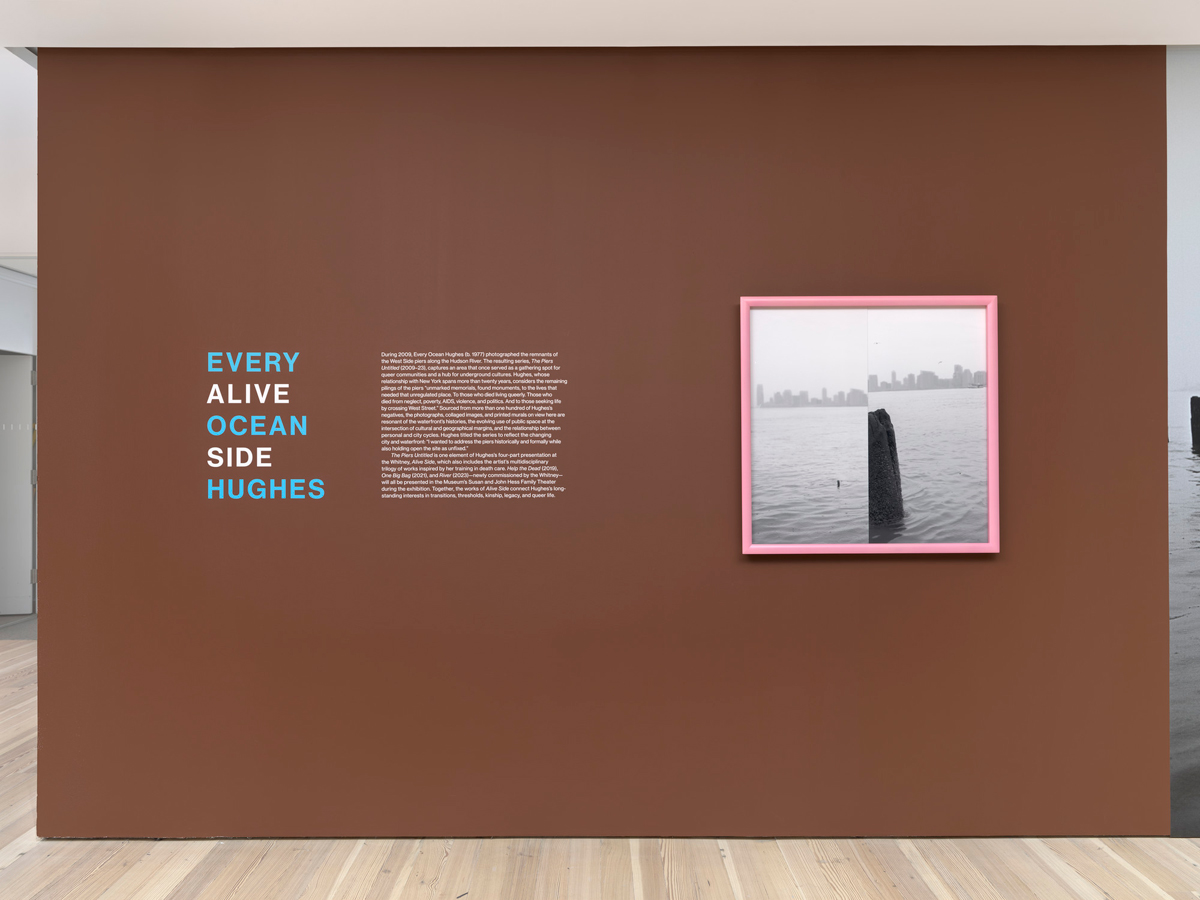

Every Ocean Hughes: Alive Side, installation view. Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Pictured, left to right: The Piers Untitled (#2), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#11 collaged), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#1 collaged), 2009–23.

Every Ocean Hughes: Alive Side, organized by Adrienne Edwards with

CJ Salapare, Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York City, through April 2, 2023

• • •

Long before the Whitney Museum moved to Manhattan’s Lower Westside waterfront, before that area became a jogger’s mecca, before Little Island and the Standard and City Winery arrived, the Hudson River piers were the domain of generations of artists and queer youth, who cruised and created there beginning in the seventies. (Think Gordon Matta-Clark, David Wojnarowicz, Alvin Baltrop, Peter Hujar.) Abandoned and derelict, the piers were also a site of political resistance by figures like trans activist Sylvia Rivera, who lived on the Gansevoort Peninsula, where she advocated for unhoused members of the queer community, until her encampment was evicted by the city in 1996.

Queer artist Every Ocean Hughes started making work related to the piers not long after she moved to New York in 1999. Some of this work—selections from the photographic series The Piers Untitled (2009–23)—is the subject of Alive Side, now on view at the Whitney. The show also includes live performances and a film installation that spring from Hughes’s training, after the loss of a loved one, as a death doula: Help the Dead (January 27–29), a musical; River (March 24–26), a new commission; and One Big Bag (February 17–20), a forty-minute film and multimedia installation.

Every Ocean Hughes: Alive Side, installation view. Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Pictured, left to right: The Piers Untitled (#2 collaged), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#13 collaged), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#7), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#5), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#8), 2009–23.

To exhibit the black-and-white photographs of Piers Untitled, Hughes transformed the Whitney’s third-floor photo gallery—a wide strip of space that visitors encounter just off the elevator—into a cheerful waiting room: the entranceway to the theater where the accompanying performances and film screenings take place. The walls alternate in swaths of party pink and muddy brown (perhaps a reference to the Hudson River) mixed in with wallpaper-size reproductions of the photographs themselves. Some of the frames are party pink, too, while others are sky blue or lemon yellow. The colors offer a sweet counterpoint to the pictures’ grayscale tone and somber, moody subject matter: shots of abandoned pilings on the waterfront on a wet, foggy day. In their bold disruption of the white cube, the colors help me know that there is celebration here, a challenge to mourn differently.

Every Ocean Hughes, The Piers Untitled (#3), 2009–23. Adhesive vinyl (printed 2022), 108 × 108 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Though the series’s title references the piers directly, at the forefront of the photographs are pilings, wood columns driven into the riverbed to support the larger structure of piers that have since been demolished. We are looking at the remains of the piers, the insistence of which calls up a state of mourning and remembering, of reckoning with ghosts and loss and memory.

Every Ocean Hughes: Alive Side, installation view. Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Pictured: The Pier Untitled (#10 collaged), 2009–23.

In addition to photographic murals, graphic play, and multicolored frames, Hughes engages with collage. The work on the brown title wall at the exhibition’s entrance is in a pink frame. It splices two photos together to show the same expanse of water and silhouetted skyline from slightly different vantages; almost in the center is a single piling, cleft by the splice’s seam, so only its right side is visible. Looking at the piling, bereft of its other half, is like blinking and missing part of the story, losing something easily taken for granted, like queer space. Next comes a wide-shot mural of the hazy Jersey skyline and a group of pilings that creep in scale down the foreground of the picture until some of them appear almost the same size as the buildings in the background, a malformed abandoned cityscape in miniature. The effect is haunting, as the sturdy edifices on the horizon devolve into a metropole of sunken misshapen remnants. Another image looks like an old graveyard, the black pilings like gravestones jutting out of the water’s surface.

Every Ocean Hughes: Alive Side, installation view. Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Ron Amstutz. Clockwise from top left: The Piers Untitled (#12 collaged), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#9), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#14 collaged), 2009–23; The Piers Untitled (#4), 2009–23.

The pilings on their own are beautiful and worthy subject matter, highly evocative, recalling tree stumps, sand-dribble castles, sexual organs. Still, some photographs are more affecting than others. Where the subject is the buildings on the surrounding piers and/or the skyline, I craved more perspective from the artist, more specificity. For a viewer without knowledge of the site’s social and historical context, the work might come across too anonymously. I found myself imposing a lot of my own research and memory onto some of the images. A question also came up for me around the Whitney’s intention with showing this series. What does it mean for a major gentrifying force of the waterfront to show art about the old waterfront in memoriam, as if the institution were a neutral, or worse, sympathetic, witness to the change?

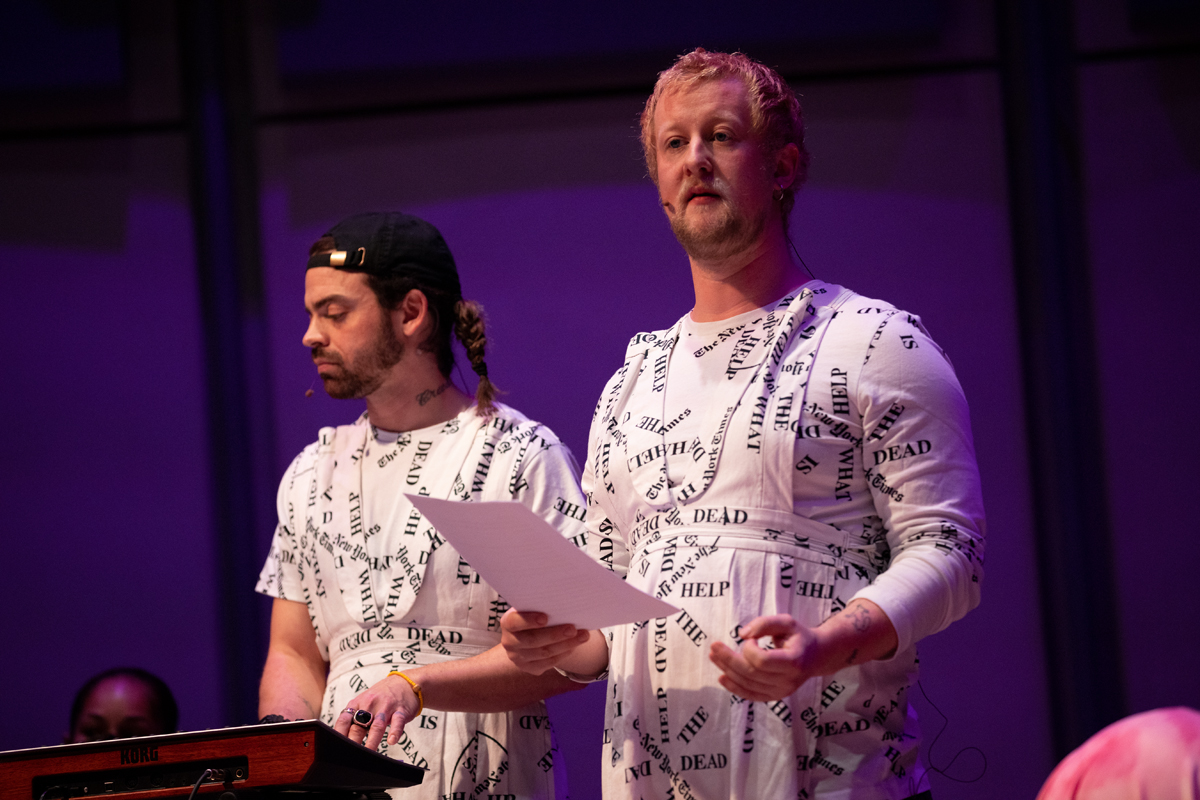

Every Ocean Hughes, Help the Dead, 2019. Live performance at the Whitney Museum of American Art in January 2023, 60 minutes. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Maria Baranova.

The performances and film shown inside the auditorium share a connection to the themes of mourning and loss in Hughes’s photographs. They are also visually linked: the theater’s glass exterior frames a view of the waterfront that is the exact terrain of Piers Untitled. I attended Help the Dead—a musical written and directed by Hughes, first performed in Berlin in 2019. The piece features longtime performers Geo Wyex and Colin Self as our guides in this theatrical concert. Together, they powerfully tag-team a stream-of-consciousness associative dialogue on death, toggling between death lessons (one section sees them narrate the process and tools for washing a dead body); commonly held ideas (a list of euphemisms for death includes “nothing but kitty litter now,” “left no forwarding address,” “took flight”); and scenes and aphorisms that encourage us to not turn away from death, to greet it with care and knowledge (e.g., Wyex and Self reading from a document called “How to support a person who is dying”: “Since it’s believed that hearing is the last sense to go, you can keep talking when they can’t respond.”). The show also recreates a death-care training session, as people from the audience volunteer to read out testimonials from an imagined community formed around death: “I want to normalize death, like birth,” one says.

Every Ocean Hughes, Help the Dead, 2019. Live performance at the Whitney Museum of American Art in January 2023, 60 minutes. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Maria Baranova.

Though the pedagogic banter and its formal shifts have the sound and shape of poetry, I found myself drifting off during these lines. It was in the performance’s music and visuals that I felt the heart of Hughes’s ideas most purely. The show hangs on two musical refrains uttered by Self and Wyex, which start to overlap as the show progresses: “When I said, ‘Help the Dead,’ I meant you / I meant you and me, / I meant you. / When I said ‘Help the Dead,” I meant you, / I meant you and me, / help you, help me. / I commit to you . . . I just wanna / get out / of my / own way.” These phrases transform into song in the style of a hymn that Wyex and Self return to throughout the performance. Their voices in combination, in perfect sonorous harmony, repeating these lyrics over and over, have a hypnotic, transcendent effect, the meaning of the words and their sounds unifying into a deeply felt, sacred entreaty: commit to life by committing to death. Just as profound, and lightly unsettling, was the show’s use of props. As the work unfolds, the performers lift sunset-colored sheets off mysterious orbs, revealing balloons that quickly ascend toward the sky, eager to rid themselves of materiality.

Every Ocean Hughes, Help the Dead, 2019. Live performance at the Whitney Museum of American Art in January 2023, 60 minutes. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Maria Baranova.

I was lucky enough to see a 4 pm showing. As the performance ended and the pink spotlights deepened, the sunset did its thing: bands of hot white, pink, and yellow, sidelighting the performance. Of course, the bright red W from the W hotel across the way in New Jersey also blazed, as it always does, morning and night, an unceasing reminder of the shoreline’s ever-present and persistent gentrification, lest we forget.

Svetlana Kitto is a writer, editor, and oral historian. Her writing has appeared in Guernica, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Cut, VICE, and elsewhere. Her book of interviews, Sara Penn’s Knobkerry: An Oral History Sourcebook (2021), formed the basis of an exhibition at the SculptureCenter.