Jennifer Krasinski

Jennifer Krasinski

Otherworldly evocations of space and the natural world in a retrospective of nineteen works.

Miyoko Ito, installation view. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. © Estate of Miyoko Ito. Pictured, left: Act One by the Sea, ca. 1955. Right: Jordan, ca. 1959.

Miyoko Ito, Matthew Marks Gallery, 522 West Twenty-Second Street,

New York City, through April 15, 2023

• • •

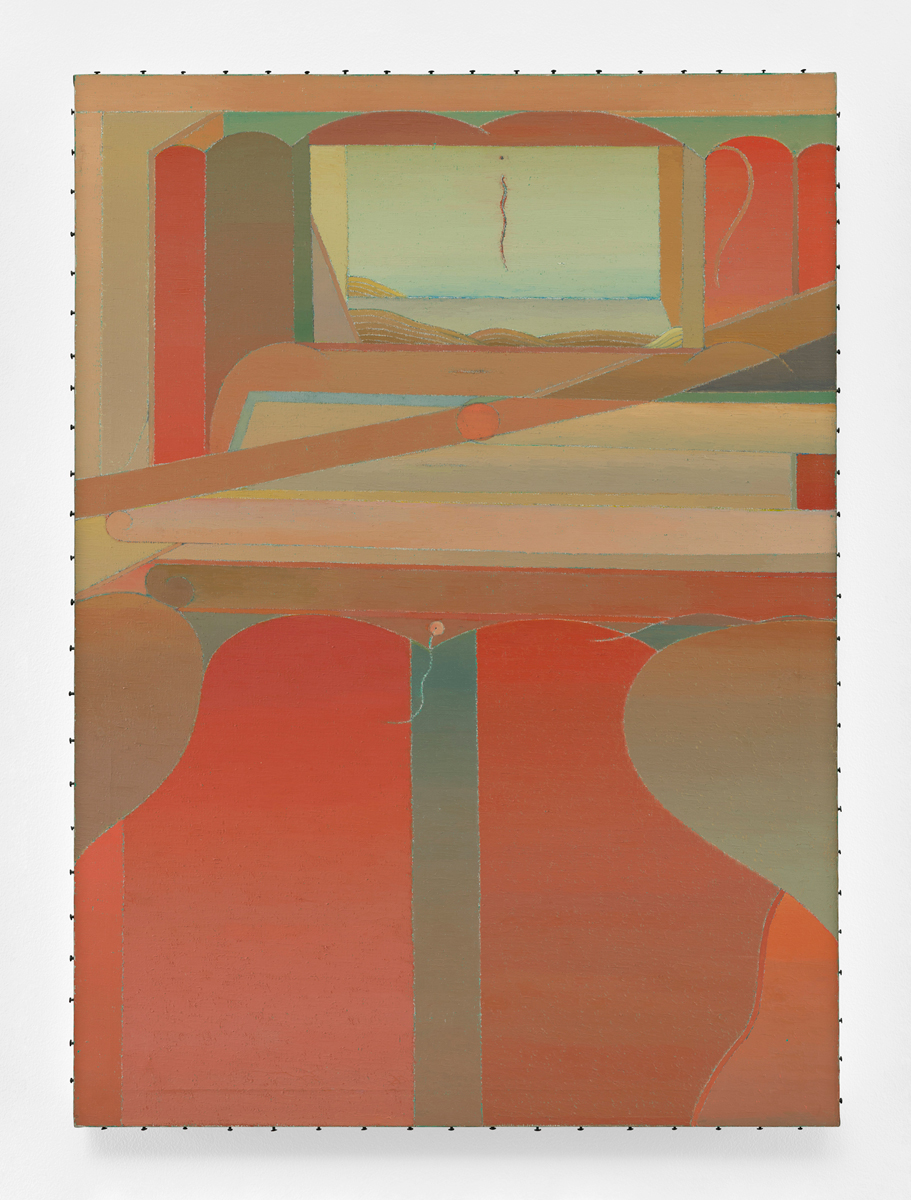

There is simply no other painter like Miyoko Ito. None. Not now, not in her lifetime. Yet even a singular hand doesn’t come from nowhere: the show of sixteen paintings and three lithographs currently on view at Matthew Marks makes vivid how Ito developed her very own brand of contemplative abstractions—dazzling, dreamlike spaces. Born in 1918, she was an art student in the late 1930s, devouring the lessons of Surrealism and Synthetic Cubism, the hangover from which can be seen in the accomplished if relatively dutiful still lifes Easel and Table (1948) and Act One by the Sea (ca. 1955). Ito also counted (the nearly inescapable teachings of) painter Hans Hofmann as an influence. His most widely atomized belief: “Only from the varied counterplay of push and pull, and from its variation in intensities, will plastic creation result.” According to Hofmann, a painter’s perpetual balancing and unbalancing of color, composition, and other elementals is what animates art with something like a life force, aerating otherwise absolute materiality with spiritual possibility.

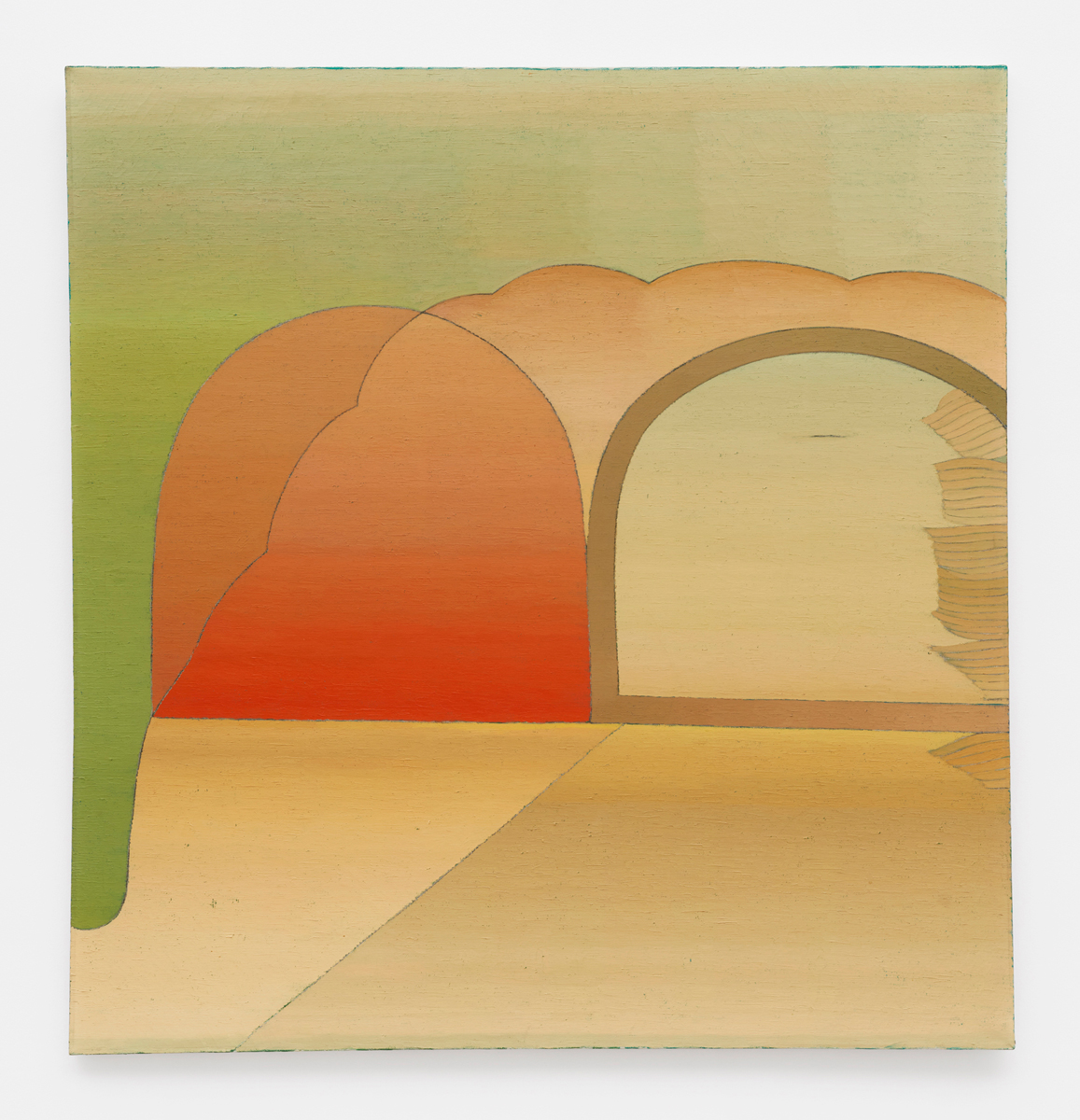

Miyoko Ito, Untitled, 1970. Oil on canvas, 48 × 46 inches. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. © Estate of Miyoko Ito.

The world invariably does its damnedest to blunt possibility. Of painting, Ito once said: “It is the only healing thing in my life. No matter what.” The daughter of Japanese émigrés, Ito grew up in Japan and Northern California. In 1942, one month before she was to graduate from the University of California, Berkeley, she and her husband, Harry Ichiyasu, were sent to an internment camp. The following year, having been granted her diploma, she enrolled in graduate school at Smith College in part so that she could leave the camp. (Though she wanted to return, the West Coast remained “off-limits” at that time to all Japanese.) In 1944, she moved to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; Ichiyasu was finally released and joined her in 1945. They lived in Chicago until she died in 1983.

Miyoko Ito, installation view. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. © Estate of Miyoko Ito. Pictured, right: Untitled, 1970.

Ito was an impeccable conductor, not just of color and line and form, but of attention. She knew how to call an eye to an artwork, compelling it to look and keep looking, encouraging it also to rest and enjoy the view. The gruff, grand Donald Judd—known for his point-blank prose and exacting opinions as to whose art was, and was not, worth regarding—positively reviewed a show of her work at New York’s Zabriskie Gallery in 1961 for Arts Magazine, remarking: “The details are subtle and inventive . . . Each composition is distinct and interesting.” I would add to that: hypnotic, exquisite, and quietly gutsy. Ito would begin her paintings by drawing on canvas in red and green, improvising sometimes for two or three weeks before the work would reveal itself. Later she deployed charcoal, because, in her words, “it erases but also leaves traces.” (Anyone in the mood to geek out about the covert operations of underpainting—those preliminary marks, hues, and layers that can be spied here and there beneath her lines and brushstrokes—will have ample chances to get deep.)

Miyoko Ito, installation view. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. © Estate of Miyoko Ito. Pictured: Flight into Landscape, 1960.

The earlier paintings in the show, such as Jordan (ca. 1959) and Yellow Sea (1959), are searching, solemn Modernist master-grapplers, intimating very little of the meticulous tranquility of what’s to come. Ito appears to make a decisive if organic transition with Flight into Landscape (1960), which ensnares the viewer in a loose knot of undulating lines and shapes—call them hillocks and valleys in the spirit of the title, which nods to a transition, too, perhaps from the subject of sea to landscape, or at least from one place to another. Flight’s palette is dominated by marigolds that darken into oranges and ochres. The eye is occasionally grounded by a brown, or popped right in the pupil by a seething red. Two half-moons, one a green-gray, the other a deep forest green, momentarily cradle your attention before you naturally rejoin the whirl. Warmth abounds.

Miyoko Ito, Heart of Hearts, Basking, 1973. Oil on canvas, 44 × 31 7/8 inches. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. © Estate of Miyoko Ito.

There are no other works on view from the 1960s, which leaves a gaping hole in the show’s albeit very informal narrative arc. Its timeline picks up again with three canvases dated 1970—two are Untitled, the third, Untitled #126—that land viewers at the height of Ito’s prowess. By then, she was painting otherworldly constructions—or are they excavations?—that draw in equal measure from architectural elements and the natural world. One question these compositions call to mind over and over again: What, if anything, distinguishes the interior from the exterior? In the trio of paintings from 1970, she plays with a common form, the arch, which you can look in, look at, and look through, sometimes all at once. In Sea Chest (1972), the arch becomes both window and mirror, bleeding one world into the next. The following year’s Heart of Hearts, Basking (1973) is a showstopper of the highest order, leaving behind the delights of such visual gamesmanship in favor of a purer experience of space. There is only a there there—which is, to this eye, the highest achievement of abstraction.

Miyoko Ito, installation view. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery. © Estate of Miyoko Ito. Pictured, left: Act One in the Desert, 1977. Right: Sea Chest, 1972.

But then there are her magnificent skies, which, when not appearing overhead, are evoked by the ever-present color gradients Ito seems to have modeled after sunrise and sunset, no matter the hues she used. Her devotion here is painterly as well as personal: as Jordan Stein—curator of Miyoko Ito: Heart of Hearts, a 2018 exhibition of her work at Artists Space in New York—beautifully noted: “while incarcerated, all she had was sky.” See the cerulean blue that descends through pink and finally turns brown as it nears the bottom of Act One in the Desert (1977), a work that recalls the arid backgrounds of Dalí and Tanguy. While Midwestern skies serve up blues that dissolve into browns, it’s California that radiates the pinks—a detail that loosely places us somewhere in memory. Toward the top of the canvas hovers a stubby comet—a circle trailed by a tail. This small thing appears variously throughout Ito’s paintings—more often than not resembling spermatozoa—and is as close as the artist gets to a recurring figure. It wriggles and punctuates, even punctures, her work, bringing to the surface the understated forward momentum that drives—that is counterforce to—its blissful stillness.

Jennifer Krasinski is a writer and critic based in Brooklyn.