Chris Kraus

Chris Kraus

Björk, Bleak House, and dinosaur Norman Mailer: a first essay collection from noted author Mary Gaitskill.

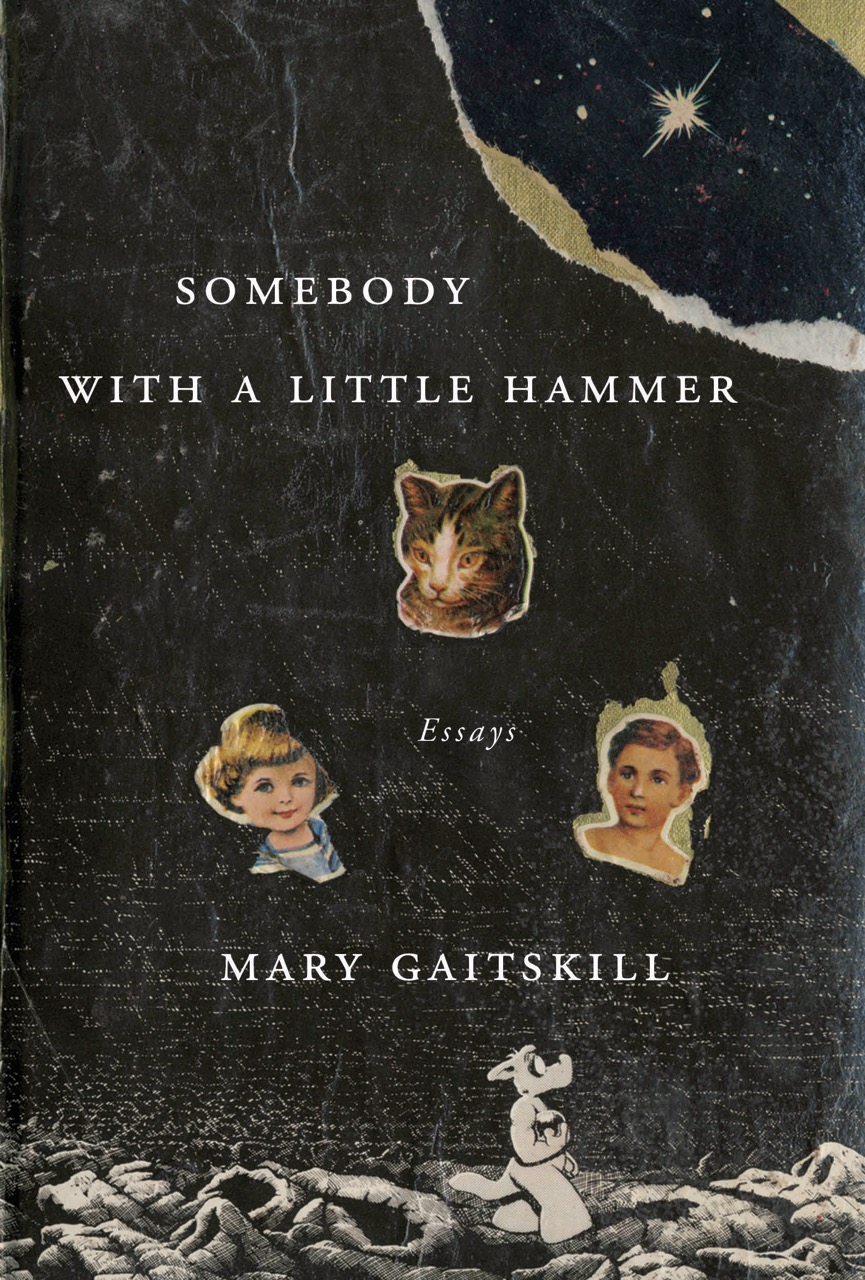

Somebody with a Little Hammer, by Mary Gaitskill, Pantheon, 272 pages, $25.95

• • •

Mary Gaitskill’s luminous fiction relies on acute observation. In all of her work, she parses distinctions between pleasure and pain, will and oblivion, nurture and harm to a point where these arbitrary distinctions collapse, and the reader is forced to enter a dark space of confusion from which real knowledge might finally begin. In one of her earliest stories, “Trying to Be,” Stephanie, an aspiring writer and sometime “professional lady” at a less-than-top house in mid-1980s New York, finds herself more violated when she accepts the attentions of a well-meaning, art-loving lawyer than when she’s humped half-on, half-off the bed by “some galoot.” In her most recent novel, 2015’s The Mare, Ginger—a blonde and “young-looking” forty-seven-year-old former artist living in upstate New York—is thrown into a maelstrom of altruism, exploitation, and mutual need when she becomes a part-time surrogate mother to Velvet, a deeply troubled Dominican girl who lives in Brooklyn.

Since her well-received 1988 debut story collection Bad Behavior, Gaitskill has published steadily but sparingly: three novels, three collections of stories. Bad Behavior’s story “Secretary” was adapted into a disappointingly romantic, but popular film. Her magnificent 2005 novel Veronica was short-listed for the National Book Award. But even at the peaks of her much-deserved acclaim, Gaitskill has limited the number of promotional profiles and interviews she submits to. She has remained relatively circumspect about the details of her own life and creative process.

Over the years, Gaitskill has filled in some of these gaps with occasional essays. Somebody with a Little Hammer gathers these pieces together: the essays explore Gaitskill’s complex ideas about fiction and form, sexuality, gender, empathy, and political spectacle with the same nuanced ambivalence that guides her fiction. Read together, they illuminate the writer’s artistic process and thought.

“In any genuine piece of fiction,” she writes in “Victims and Losers: A Love Story,” “the plot is like the surface personality or external body of a human being; it serves to contain the subconscious and viscera of the story.” She’s making an argument for what was lost in the film adaptation of “Secretary,” but at the same time, she’s describing the aesthetic vision that runs through all of her writing. Fiction, she infers, occurs through displacement. It’s only through a collision of feeling and form that received ideas can be called into question.

It’s no coincidence that several of her essays concern music and musicians—Bob Dylan, Björk, Talking Heads, the obscure B-movie song “Nowhere Girl”—because her notion of how fiction works is incredibly musical. In “And It Would Not Be Wonderful to Meet a Megalosaurus,” an inspired reading of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House, she suggests that what seems like repetition in the long novel might in fact be a “deepening, rapidly taking you through layers of images and movement that develop your sense of the character and his world almost nonverbally—an extraordinary thing in a verbal medium.” The monochromatic goodness of Bleak House’s protagonist Esther should not be misread as a cartoon. Rather, Esther’s presence “is like that of an operatic singer—a pure, high ribbon of sound that simultaneously pierces and unites the complex ‘music’ of the other voices, images, and kinetic movement.”

Gaitskill’s notion of American history, culture, and class is similarly nuanced. She isn’t afraid to call out political correctness, and she’s scathing in her critique of “female empowerment” and redemptive confession. “Americans,” she writes in “Victims and Losers: A Love Story,” are “terrified of being victims, ever, in any way.” As she explains, “I think it is the reason every boob with a hangnail has been clogging the courts and haunting talk shows . . . telling his/her ‘story’ and trying to get redress. Whatever the suffering is, it’s not to be endured, for God’s sake, not felt and never, ever, accepted. It’s to be triumphed over.” Likewise, in “I See Their Hollowness,” she takes reviewers of the Beirut-born writer Rawi Hage to task for overpraising his work. She finds Hage’s scabrous depictions of wealthy Canadian women inept and cartoonish. Critics who hail him as a genius are subtly disrespecting his work by indulging their own masochistic white guilt. Presciently, she notes in her 2006 title essay how “very little now seems to occur behind the scenes except for the exercise of power.”

Revisiting Norman Mailer’s legend and work in her 2009 essay “The Doughty Nose,” Gaitskill detects a cultural war that is not over yet. Mailer, to her, is a tragic figure, not unlike Richard Nixon. His bombastic pose reflects his powerlessness. Reading Mailer’s account of his participation in a Vietnam War protest in The Armies of the Night, Gaitskill detects the Great Writer’s malaise. Time has passed Mailer by, and among his New Left and countercultural colleagues, he is clearly a dinosaur. The real war, Gaitskill writes, has nothing to do with actual politics, and everything to do with culture and class. Mailer, to her, was an American original of an already-lost, mid-twentieth-century world. His broad form of ego comedy laced with violence and sex reflected “a whole called America.” Watching him up against Gore Vidal in a debate about feminism on The Dick Cavett Show when she was a teenager, she pitied the self-proclaimed “male chauvinist pig.” While Vidal made all the right points, the young Gaitskill felt that watching him “was like watching a snake in a suit, all piety and fine manners, standing up on its hind tail to recite against the evils of sexism. Before this fancy creature, Mailer was nearly helpless, lunging and swiping like a bear trying to fight a snake on the snake’s terms.” As in her fiction, Gaitskill sees everything. She sails beyond the literal content of their conversation to access the sadness of what it’s like to outlive one’s own time. The narrator of her novel Veronica has a similar insight. Observing her father’s poignant regard for his favorite World-War-II-era singers, she understands that his musical preferences “signaled a mix of feelings that were secret and tender,” but they were signals no one could read anymore.

The essays in Somebody with a Little Hammer are as dense and as rich as Gaitskill’s fiction and further establish her as the important critical thinker she’s always been. Her extreme sensitivity makes her one of the most reliable witnesses to life in the US. As she writes: “Everything is too mixed now; too many things are mixed. I am too small to hold it all, and if I try, I will break.”

Chris Kraus is the author of four novels and two books of art and cultural criticism, including I Love Dick, Summer of Hate, and Where Art Belongs. Her forthcoming biography of Kathy Acker will be published by Semiotexte in September 2017. Chris Kraus lives in LA, where she is a co-editor of Semiotexte, and teaches writing at European Graduate School.