Sowon Kwon

Sowon Kwon

Glyphs, ribbons, French knots: revisiting the

Pattern and Decoration movement.

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon.

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, curated by Anna Katz with Rebecca Lowery, Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, through November 28, 2021

• • •

Launched in the early 1970s, the Pattern and Decoration movement embraced craft and decorative arts traditions in defiance of the perceived austerity and reductive vocabulary of prevailing idioms in Minimalism and Conceptual art. Having traveled from MOCA Los Angeles, where it opened in October 2019, a survey of the movement—With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985—is now on view at the CCS Bard Hessel Museum of Art. Featuring painting, sculpture, collage, ceramics, textiles, installation art, and performance documentation, the exhibition showcases key works and introduces new scholarship as an important reclamation of Pattern and Decoration.

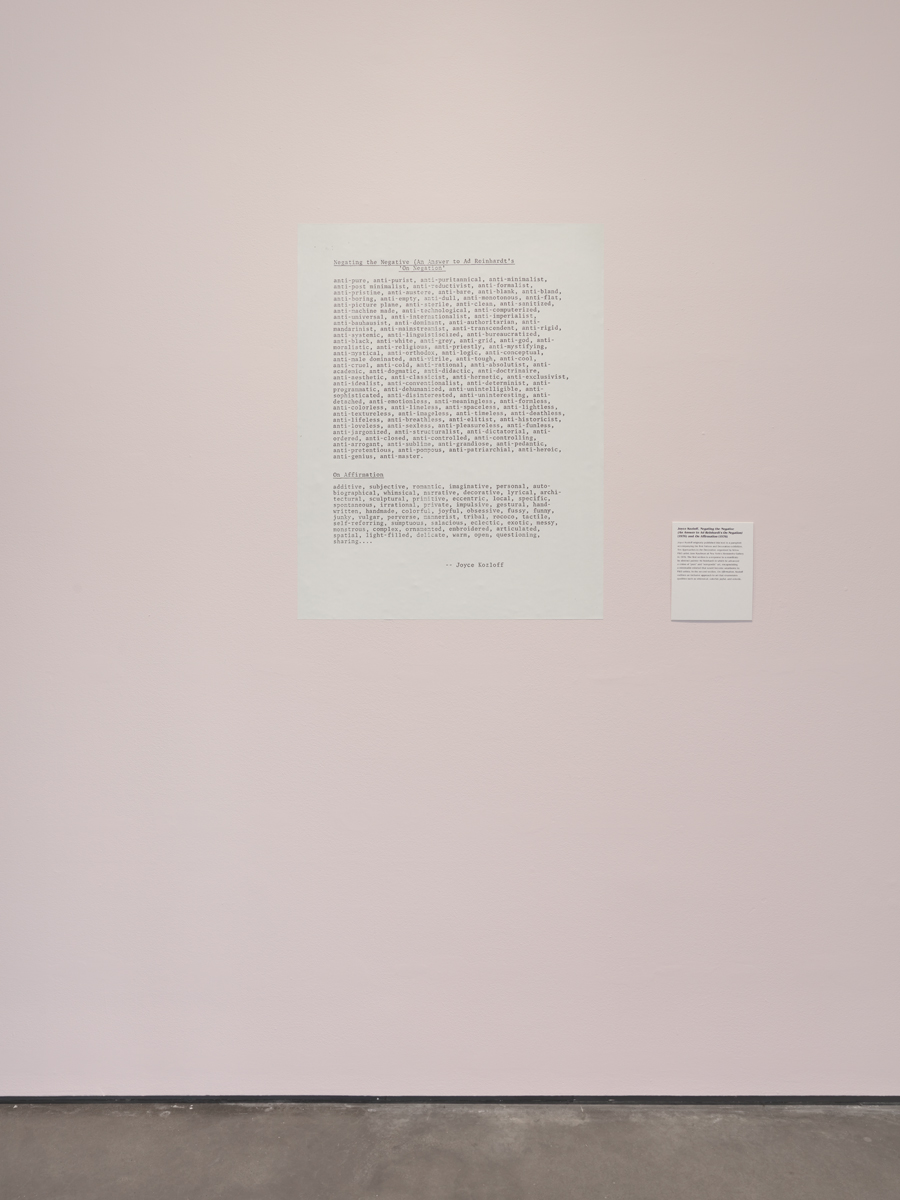

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Pictured: Joyce Kozloff, “Negating the Negative (An Answer to Ad Reinhardt’s On Negation),” 1976, and “On Affirmation,” 1976.

In a would-be manifesto from 1976, artist Joyce Kozloff defined P+D in pointed negation: “anti-pure, anti-purist, anti-puritannical, anti-minimalist, anti-post minimalist, anti-reductivist, anti-formalist . . .” A dense block of typewritten text, the list goes on: “anti-imperialist, anti-bauhausist . . . anti-logic, anti-conceptual, anti-male dominated,” ending “anti-heroic, anti-genius, anti-master.” But if modes of opposition are a hallmark of modernism, even avant-gardism, Kozloff’s text may be somewhat symptomatic of what it sets out to resist. Plus, as the homes of collectors of postwar American art attest, works by Carl Andre, Donald Judd, or Dan Flavin can play nice with modular seating, floating bookshelves, and recessed lighting. (Which was purchased and installed first?) Not only is “minimalism” in interior design a thing, but disconcertingly, Minimalist art can be as decorative as not.

Jane Kaufman, Embroidered, Beaded Crazy Quilt, 1983–85. Embroidered thread and beads on quilted fabric, 94 × 82 inches. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Joshua Nefsky.

So, what can a reassessment of the P+D movement offer us now? Are there unforeseen points of convergence between it and its detractors? Has it “opened up new avenues in . . . feminism, abstraction, and installation art,” as curator Anna Katz proposes? Such questions are explored as thoughtfully in the exhibition catalog (perhaps more so) as in the show, which features work by Kozloff and other foundational members, including Valerie Jaudon, Robert Kushner, Tony Robbin, and Robert Zakanitch; as well as underrecognized (and, in some instances, unprofessed) figures, including Emma Amos, Tina Girouard, Mary Grigoriadis, Diane Itter, Al Loving, Dee Shapiro, and Takako Yamaguchi. In the corrective mode of our day, which attempts to redress historical exclusions, Katz also highlights quilting, “a centuries-old American tradition, practiced largely by women, usually anonymously and often collectively, with a particular legacy in African American culture” as a “leitmotif” of the show.

Miriam Schapiro, Heartland, 1985. Acrylic and fabric on canvas, 85 × 94 inches. © 2021 Estate of Miriam Schapiro / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Zach Stovall.

More so than the civil rights movement, which registers only belatedly through curatorial reach, the impact of second-wave feminism on P+D artists, and its convergence with their interest in decoration and handicrafts, is foregrounded in many works, such as Miriam Schapiro’s “femmage” Heartland (1985), an outsize valentine in acrylic collaged with floral and metallic fabrics, and Jane Kaufman’s meticulous Embroidered, Beaded Crazy Quilt (1983–85), in which an almost-encyclopedic skill set in stitchery is demonstrated, from feather to chain to French knots and on.

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Pictured, left: Sam Gilliam, The St. of Mortiz Outside Mondrian, 1984; right: Al Loving, Untitled, 1982.

Needle and thread, the sewing machine, fabric dye, sequins, pastry bags and tips, tile, porcelain, and hole punches figure as serious production tools as much as paint and brushes in the assembled works (by Lucas Samaras, Alan Shields, Lia Cook, Kendall Shaw, Pat Lasch, Ralph Bacerra, Howardena Pindell), with most falling into the catchall category of “mixed-media.” Another favored medium is the constructed relief; examples of both high and bas toggle between the pictorial and sculptural in their dimensionality, tactility, and orientation (Sam Gilliam, Loving, Frank Stella, Betty Woodman). Less persuasive for this viewer are efforts that feel overburdened by iconographic signification—encrusted fans, gestural glyphs and washy plaids, fairies, a bunny, pastel flower petals, doilies. It must be said that large portions of the show would fit right in, possibly by design, in hotels and their gift shops, decidedly on the side of twee and cringey.

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Pictured, center on back wall: Ree Morton, One of the Beaux Paintings (series), 1975.

Among exceptions are Ree Morton’s paintings of bows/“beaux” in which such a dig has been anticipated. Her celastic ribbons and borders, both animate and fixed, light yet bold, two-dimensional and three-, render all such terms legible while holding them in tension and wit. As puns do, her touch goes in different directions simultaneously. Also of note are works of “composition by accretion” (as cited by Katz) that build upon the structural logic of patterns as nonhierarchical fields rather than having a central focal point (Tony Bechara, Constance Mallinson, Neda Alhilali). The show would suggest that such works have egalitarian social implications. Cued by textiles and needlepoint, they perhaps also anticipate networks and rasterized digital-imaging systems. In addition, the theoretical provocation that the decorative and pattern are repressed in the modernist grid is compelling food for thought.

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Pictured, left to right: Brad Davis, Rabbit + Two Dogs = Desire, 1979; Top of the Peak, 1980; Bird & Lotus Tondo #4, 1979.

For all the maximalist exuberance espoused by practitioners and emphasized by the museum’s wall texts, though, the show as a whole felt somewhat sparse and staid. Perhaps it was a livelier story in LA, but upstate, it was all too similar in volume and pacing to many an elegant exhibition that adheres to institutional conventions: works hung so high, with a tasteful distance between them. P+D thematics would seem to call for more overall spatial experimentation and adventurousness in exhibition design, given their engagement with décor, architectural scale, and immersive environments.

Speaking of architecture, it is fitting that some P+D works share the pastiche aesthetics of contemporaneous postmodern architects (Ned Smyth’s cement and mosaic columns). Along those lines, the characterization and rationale for P+D’s free appropriation of other cultural traditions as “homage” is unsatisfying. Homage can be dilutive after all, and not necessarily welcome. Evidence of travel and a vague “love” (for pre-Colombian textiles, kimonos, thangkas, Mayan facades, Islamic girih, kente cloth, Persian music, miniatures, and chadors), however unironic, do not necessarily give license or absolve all, just as artistic intention does not equal the meaning of the work.

Consider P+D’s affinity (need?) for cultures without a formal distinction between fine and decorative arts. In Japan, as an example, for better or for worse, this undifferentiation/de-hierarchization has not been categorically true for over a century. Such oversimplification in which the fact of the asynchronous temporalities of global modernisms is inconvenient, is telling, and raises a question that is sadly not new: At what cost ahistoricism and (white) self-actualization?

P+D’s merit may be in its incompleteness as a project, inviting reassessment not only of the movement proper, but how it might further illuminate works we think we already know. Hamza Walker’s catalog essay triangulates P+D with conceptualist Daniel Buren and abstract painter Rebecca Morris. Katz insinuates P+D’s legacy with those of Anni Albers, Sonia Delaunay, Natalia Goncharova, Hilma af Klimt, even Andy Warhol. Could we add Sigmar Polke and Sheila Hicks? And numerous other contemporary artists come to mind, notably Sanford Biggers, Anoka Faruqee, and Cauleen Smith. Do their practices signal a reclamation or a continuity?

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Pictured, right: Sylvia Sleigh, The Turkish Bath, 1973.

Thinking again about Kozloff’s 1976 text “Negating the Negative” alongside Sylvia Sleigh’s oil painting The Turkish Bath (1973), which features a nude male “harem” of art critics sympathetic to P+D (John Perrault, Carter Ratcliff, and Lawrence Alloway as odalisque), had me wondering if such inversions could be analogous to the writerly “error” that is the double negative. Repetitive and potentially confusing—both text and picture are displacements of a kind in any case. At the show, two ladies of a certain age blocked my view of Sleigh’s painting for a good while. At her companion’s elaboration on the composition, the frailer of the two marveled, louder than she probably intended, “Well, that is powerful!” At her booming vocalization, I felt a bit shamed, in my impatience. No doubt they were not the only two whose hard-won, long-held passions were affirmed by the ethos of this show. And that’s not nothing.

Sowon Kwon is an artist based in New York City. Her work can be viewed at Broodthaers Society of America and Triple Canopy magazine. She teaches in the Graduate Fine Arts Program at Parsons / The New School, and, as a member of G11, is currently co-organizing Looks Like Play for the Virtual Asian American Art Museum (VAAAM).