Reinaldo Laddaga

Reinaldo Laddaga

In Buenos Aires, an obsession with a magazine from a distant land.

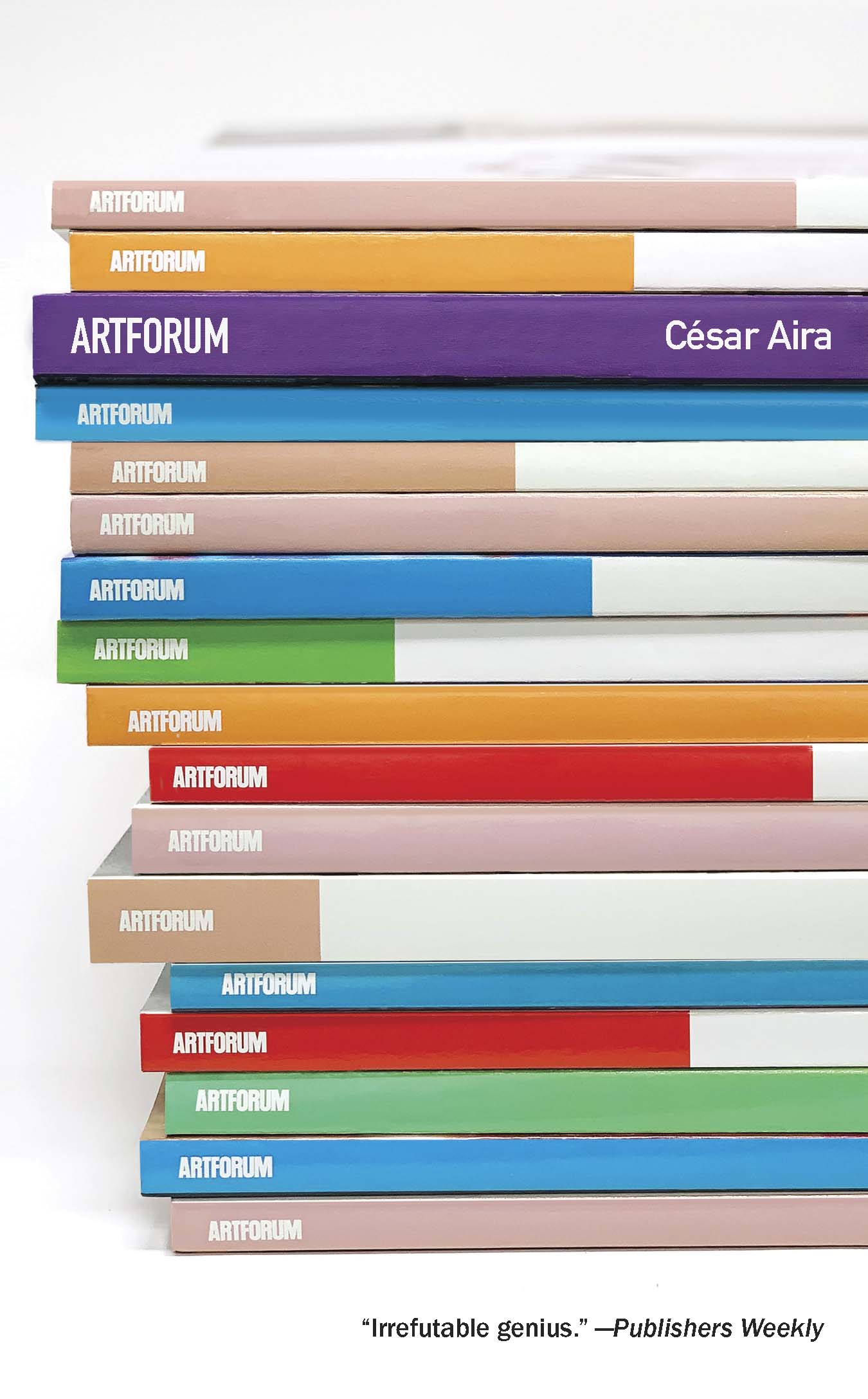

Artforum, by César Aira, translated by Katherine Silver, New Directions, 82 pages, $13.95

• • •

It’s a tricky business to introduce English-language readers to César Aira, who was born in 1949 and is perhaps the most acclaimed living Argentine writer. I used to teach some of the roughly one hundred volumes he’s published so far to my students at the University of Pennsylvania. I’d include one of his brief novels or essays in a syllabus, only to be met again and again with puzzled young faces that asked, “Is this all?”

I didn’t totally blame them: Aira’s texts tend to give the feeling of being barely finished, the works of an impatient craftsman who, in the midst of completing a piece, couldn’t wait to start the next one. But taken together, his books (for decades he has issued as many as four or five a year) amount to a massive collection of interlocking miniatures. In some ways, each volume is a chapter in a saga that includes an enormous number of characters, usually orbiting around a perplexed man of artistic inclinations not dissimilar to the way the author likes to present himself. This is definitely the case with Artforum—the latest (and eighteenth) of his English translations: its narrator is an obvious stand-in for Aira. And while the volume may be slim, it is a surprisingly rich work. For those who have not read him, it is also an excellent place to start a relationship.

The eleven short pieces that compose the book are chronologically organized. They begin with a text from 1983, when the then-young author, who lives in a middle-class neighborhood in Buenos Aires, declares his greatest object of desire to be the magazine Artforum (“my luxury, my fantasy”). The few copies he manages to obtain from secondhand bookshops or friends who travel are carefully stacked with other periodicals on a coffee table, seemingly safe for repeated perusing. But one day disaster strikes: rain pours through an open window onto the pile. This would have ruined the entire collection if one of the Artforums hadn’t soaked up all the water, sacrificing itself so that the rest could stay dry. Or so it seems to the troubled collector, who marvels at the view of the multicolor, bulging sphere as it stands on top of the stack as if on a pedestal. He feels the martyr is even more precious now that it is entirely illegible.

He won’t be able to read the magazine, but perhaps, after all, its contents never mattered: its value may have always resided in it being an emissary sent to the remote end of the world from the changing frontier of the Present, in its most luring incarnation for the provincial aesthete—the New York art scene, circa 1980. The advent of the messenger, not the (inevitably trivial) message, is what counts.

Artforum expresses the relationship that the narrator has with the magazine he loves as a series of stages in his maturation. The first, juvenile phase is characterized by his more or less joyful acceptance of chance. Artforum is not looked for: it can only be found. Neither the moment nor the place of arrival is known, and the sheer randomness of its appearances constitutes “that rhythm without rhythm my life had come to terms with since my youth.” But this pristine, somewhat innocent stage cannot last: another accident (the arrival of an unsolicited credit card) triggers the start of a second phase, incipiently adult, when he attempts to turn from being the passive recipient of a modest miracle to the active agent of his own fate: the narrator subscribes to the magazine.

Having done so, he hopes that an element of order will be introduced into his world and that predictability will reign. But the expectation is frustrated: the distance between Buenos Aires and New York is as vast as the distance between the town and the castle in Franz Kafka’s eponymous novel. The carriers stray off; the postal system breaks down: the magazine rarely comes when expected—if it comes at all. Like the engineer in The Castle, Aira’s subscriber adopts the habit (and discovers the joys and sorrows) of waiting. His purgatory is punctuated by moments of extreme satiety (as when he’s able to buy twenty-four copies of Artforum at the same time) and periods of deep melancholy, when the absence of the magazine throws a gray veil over the world. This period of waiting is sometimes lyrically, sometimes comically recounted in a series of texts from the early 2000s that form the bulk of the compact volume.

The three concluding narratives (written close to the book’s 2014 publication in Argentina) describe the last phase of the relationship. The helpless subscriber has been suspecting for a while that his puerile attachment to Artforum has causes that he doesn’t comprehend: “What I was waiting for,” he ponders, “was something else, which was hiding in the invisible shell of the Other.” The magazine may be a “cloaking object,” and there’s reason to think that “underneath it there appeared—or better said, there was hiding—a fearful presence, a powerful entity that had adopted it to disguise itself.”

Something nameless and potentially sinister has been hovering behind the innocent appearance of an art magazine, and maybe it’s time to bring it fully to light. The writer conceives a magnificent project: to make his own personal Artforum, with all the fanatic care of the most committed hobbyists, and, channeling the years of passion he’d devoted to a literary project into a disinterested handicraft, achieve a final, inviolable autonomy.

The fantasy never materializes, but something much better occurs: Artforum disappears. It completely stops coming, for no reason, and best of all it doesn’t matter. The bond has been broken, and now that both expectation and anxiety have ceased, he conjectures that his years as a subscriber were a long, inadvertent apprenticeship in learning to renounce the effort to actively structure his life in order to simply live it. The book ends with a short page where Adam, the first man, confronts the world when it has just begun, when “it had barely begun to accommodate its elements” and “forms were born, wrapped in the shimmering dampness.” Adam hears the first song of a bird; the image corresponds so closely to colonial European fantasies of the American man as a creature free of concerns, living in a germinal, endlessly blooming nature, that we have to wonder if we are being invited to make a geopolitical reading of it—the Center has lost its lure as the privileged seat of the Present, the world is everywhere equally old and fresh, everything is contemporary.

Perhaps this is the case, but nothing is certain: Aira’s text may be as much a “cloaking object” as the narrator suspects his beloved magazine to be, its meaning as indeterminate as the identity of the real object of the subscriber’s vigil. And if I said that this book is an excellent place to start a relationship with Aira, it is because all the decisive elements of his work are here: the proliferation of events that link the numinous with the most banal domesticity, the cosmic with the inhabitants of a middle-class neighborhood in Buenos Aires; the more or less esoteric references to contemporary art and the philosophical tradition caught in the web of a writing that is deceptively plain; the book as a loose gathering of disparate narratives that adopt the pose of casual improvisations, textual toys fabricated to keep boredom at bay and wonderment close at hand.

Reinaldo Laddaga is an Argentine writer based in New York. The author of numerous books of narrative and criticism, he taught for many years in the Romance Language Department of the University of Pennsylvania. His latest books are Los hombres de Rusia (The Men from Russia), a novel, and a forthcoming study of Andy Warhol’s practices of fashioning.