Reinaldo Laddaga

Reinaldo Laddaga

Unnamed narrator, unnamed menace: a new translation of the powerfully unsettling 1969 novel by Argentine writer Antonio Di Benedetto.

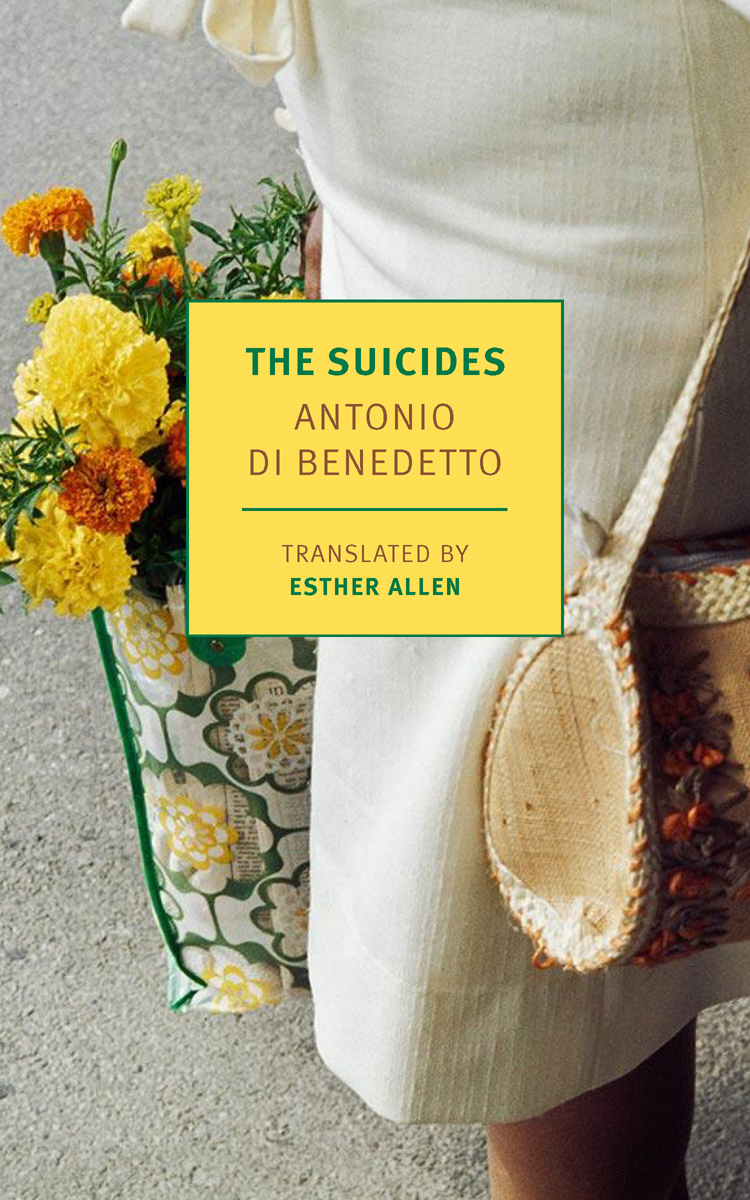

The Suicides, by Antonio Di Benedetto, translated by Esther Allen,

New York Review Books, 165 pages, $16.95

• • •

Antonio Di Benedetto’s writings exert a subliminal influence on me: under their spell, time lags, and the world of people and things acquire a blurred, phantasmagoric tenor. That’s how I felt while reading Esther Allen’s excellent new English-language translation of The Suicides, which I first encountered in Argentina in the mid-1980s. (It was originally published in 1969.) At that time, it was almost impossible to find Di Benedetto’s books in stores, with the exception of his best-known and probably most brilliant work: a 1956 novel called Zama (a Kafkaesque fantasy about a colonial official in eighteenth-century Paraguay). Until 1999, when an Argentine publishing house initiated a program to make the author’s complete oeuvre available again, his books were cult items that passed from hand to hand.

The Suicides—Di Benedetto’s third novel and one of his best—opens when a news agency receives an envelope containing three photographs of people who had died by suicide a few months earlier. Two have the exact same disturbing expression: their mouths exude sublime pleasure while their eyes are fixed in horror. Taking the images as a starting point, a journalist from the agency decides to carry out an investigation of the possible motivations of the suicides for an illustrated article. The book’s narrator is this journalist—an unnamed man who lives with his mother and brother and the latter’s family and has a vague, sentimental relationship with an elementary-school teacher. Everything takes place within the framework of the well-educated Argentine middle class of the time, peopled by young professionals endowed with a considerable artistic and philosophical culture, as well as a generally reflective attitude toward life. They are readers of Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre who wonder about the meaning of existence and are stuck in unfulfilling jobs that they perform with anomie. The most epochal aspect of the book is its portrait of an urban caste who, with the decline of traditional Catholicism, has lost any horizon of transcendence.

The narrator is a fan of boxing and science-fiction films. For the rest, he moves around a nondescript city feeling sudden bouts of attraction for this or that woman: he admires the legs of a coworker, is enraptured by the faces of passersby, fantasizes about a provocative teenage girl he interviews for his article, and, finally, strikes up a relationship with the photographer with whom he is investigating the suicide cases. He seems dominated by a more or less constant arousal that leads him to approach the world as a set of (firmly heterosexual) erotic possibilities. But it is a weak impulse; he gives up when he thinks a conquest would take too much effort, and the seductive maneuvers he attempts are brusque and clumsy. He exists in a state of drowsiness, and the motives of his actions are often obscure to him—he seems less an actor than a spectator of his existence. The course of his life is an endless oscillation between paralysis and shock.

The story is told in the first-person present, from a perspective that merely notes what is encountered and, like the French nouveau roman, reveals as little emotion as a camera. We readers have access to what is happening in flashes, scenes separated by uncertain periods in which characters enter who shine for a moment only to sink into the shadows immediately, as happens in dreams. The women, who are one of the narrator’s few objects of interest, are little more than names placed over nebulous identities, and the world is an entropic collection of details. The narrator’s other interest is in suicides, a subject that touches him personally: his father killed himself at the age of thirty-three, the age he is about to reach. This fact makes him want to discover if the desire for suicide is transmitted along genealogical lines; is it a destiny to which he will be unable to object? The research, conducted with a view to the article that we suspect he will never write, leads him to witness and imagine atrocities that he notes with an amanuensis’s calm. A suicide is dug up, his hand is cut off, and then he is reburied; two teenagers—one with a shattered chest—lie under tarps that the police lift for their parents to identify.

Everything is rendered with the same apathy; the effect this produces is similar to the one found in Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster series, painted a few years before Di Benedetto’s novel was first published. I think in particular of an image made with successive silkscreen prints, increasingly blurred, based on a photo of a dead woman’s body prone on the hood of a black limousine; the woman threw herself from the height of a building and lies placidly on the metal that seems as soft as a mattress on which she might take a nap. The image is powerfully incongruous: the violence of the collapse doesn’t register on the painting’s ornamental surface, and the artist’s affection seems inadequate to the tragedy he depicts.

“Everything is a fantasy,” Warhol used to say. As in Franz Kafka’s narrative (an evident influence on Di Benedetto), life is a dream, brief, murky, and governed by laws that we can neither hope to grasp nor be able to resist. The Suicides’ narrative strategy—using the first person in the always-changing and ever-monotonous present—makes us feel that the protagonist’s relationship with himself as a character in the novel is a bit like that of the dreamer who witnesses his own image in a dream. As frequently happens in the short stories of Jorge Luis Borges, there’s the suggestion that he is, in some way, the dream of others. Following a venerable custom of Argentine literature, widely practiced by two of the most significant writers of the twentieth century (Borges and Roberto Arlt), Di Benedetto suggests that a vast conspiracy may be the basis of otherwise inexplicable incidents. Perhaps the members of a sect of wealthy men who have pledged never to die sent disturbing photos to a certain news agency so that the wheels would start to turn to bring the narrator to the very brink of death. But we will never know if they did or why, and, in the end, we are left with the impression of having attended a theater of languid puppets who do not know or care who moves them. The book’s great virtue is that, using austere and bluntly cryptic prose, it builds the feeling of an unnamed and perhaps unnamable menace dwelling just behind the veil of words and suspends us in a state that doesn’t dissipate when we close its covers—of someone who, rising from a particularly intense nightmare, doesn’t know the extent to which, or even whether, she has woken up.

Reinaldo Laddaga is an Argentine writer based in New York. The author of numerous books of narrative and criticism, he taught for many years in the Romance Language Department of the University of Pennsylvania. His latest works are Los hombres de Rusia (The Men from Russia), a novel, and Atlas del eclipse (Atlas of the Eclipse), a book about walking in New York at the height of the COVID crisis.