Jeremy Lybarger

Jeremy Lybarger

Derek McCormack offers a comic novel of flamboyant depravity.

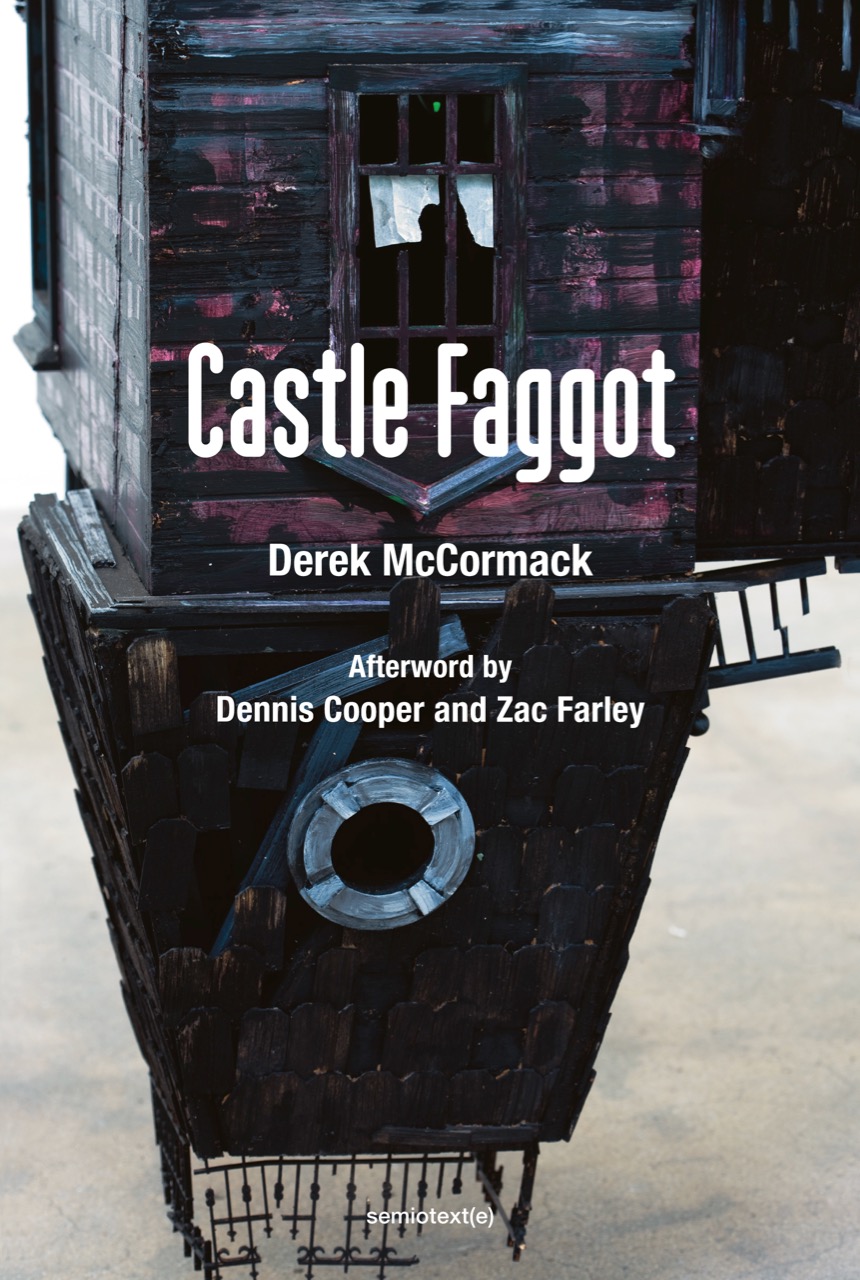

Castle Faggot, by Derek McCormack, Semiotext(e), 98 pages, $15.95

• • •

In 1963, Tommy Kirk, the child star of Old Yeller, The Shaggy Dog, and Swiss Family Robinson, had a falling out with his employer, Disney. The cause was the twenty-one-year-old actor’s dalliance with a fifteen-year-old boy he’d met at a Burbank swimming pool. The boy’s mother discovered their affair. “Disney was the most conservative studio in town,” Kirk said later, and nothing sours a family brand faster than sodomy. Walt Disney himself reportedly fired Kirk.

After that, Kirk’s career entered a stretch of wilderness years typical of a fallen celebrity. He developed a drug habit and appeared in a string of increasingly abysmal B movies; among them, It’s a Bikini World and Blood of Ghastly Horror. In the mid-’70s, he abandoned Hollywood, got sober, and went into the carpet-cleaning business. He’s retired now. As far as I can tell, he lives in an actual wilderness in Redding, California. “Monte Carlo it is not,” he told a newspaper reporter in 2006.

Kirk is the patron saint of Castle Faggot, the new novel by Derek McCormack. He’s never mentioned outright, but the book’s phantasmagoria of queer martyrdom, of a world in which gay men commit suicide and become literal decor, is of a piece with Kirk’s amputated career. The difference is that whereas the real Disney jettisoned Kirk to safeguard the studio’s revenue and reputation, McCormack’s version—Walt Doody—is himself a gay paterfamilias who presides over a giddy orgy of death.

The name Walt Doody signals what kind of novel Castle Faggot is: a sideways roman à clef, playful and puerile, but also unremittingly scatological. McCormack is a Canadian writer often compared to, and affiliated with, Dennis Cooper (whose conversation with filmmaker Zac Farley constitutes the novel’s afterword). Both writers share an almost fetishistic devotion to bodily functions, sexual degradation, and the corruption of youth; both revere small and alternative presses; both write in a style that’s as spare and declarative as a fortune-cookie prophecy. But McCormack’s aesthetic, honed over a dozen books, is more elliptical and allusive. His true precursors are Pier Paolo Pasolini, Georges Bataille, J. K. Huysmans, and Kathy Acker. Lest that pedigree make McCormack sound too highbrow, know that Castle Faggot burbles with puns, deliberately lame jokes, snippets of fictional songs, internal rhymes, and geysers of flamboyant depravity. The novel’s intertextual references are a casebook of camp eclecticism: The Wizard of Oz, scrying, the French Decadents, breakfast cereals, the sixteenth-century British astronomer and occultist John Dee, the 1964 TV special Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, funhouse mirrors, the child murderer Gilles de Rais, etc. Like aspartame, McCormack’s work delivers an artificial sweetness laced with carcinogens.

If I had to summarize Castle Faggot at gunpoint, I’d say it’s basically a satire of an amusement park modeled on Disneyland. The heart of the park is Faggotland, which is designed to look like Paris, “the faggiest city.” And at the heart of Faggotland is Castle Faggot, a haunted castle full of (literal) shit and the bodies of gay men who killed themselves. (“Why do faggots commit suicide? Why not?”) The chaperones of this grim debauch are Count Choc-o-log, Boo-Brownie, and Franken-Fudge, excremental knockoffs of General Mills’s monster cereal mascots. They aren’t so much characters as manifestations of the novel’s premise: “All faggots are cartoons.”

To call the novel a satire, though, is to pasteurize it somewhat, or reduce it to generic conventions of exaggeration and catcall. Castle Faggot is an experience—its own biosphere, its own zip code. Or, more apropos, it’s a creaky coaster always one switchback away from derailment. Structurally, it feels like being handed a dossier of samizdat. Part one of the book is a mock travel brochure advertising Faggotland’s amenities—rides such as the Buttfuck Bumper Cars, restaurants including Le Mâche-Merde—that also markets it as a place for queers to kill themselves. Part two is a souvenir photo book whose photos are all blank squares, the apotheosis of a fantasy vacation. Part three is catalog copy for the Castle Faggot Dollhouse: “It lets you play as a dead faggot. It lets you be a dead faggot—shove the castle up your ass and rupture your rectum.” And part four is a novelization of Rue du Doo, a puppet show featuring characters inspired by fin-de-siècle poets (Stéphane Marshmallarmé, Arthur Rainblo) and haute-couture moguls (Cocoa Chanel).

The four sections hang together by mood and motif rather than anything approximating plot. If the novel were only clunky puns and one-liners (“ ‘Who makes monster makeup?’ I say. ‘Cover Ghoul’ ”), it’d quickly overstay even its brief page count. But by embracing the gimmicky tawdriness of his material, McCormack seems to say, yes, this is all obviously moronic, but look beneath the hijinks. The dichotomies of top/bottom and inside/outside pervade the book—and are another queer pun. McCormack reifies these in the layout. A little more than halfway through, the text is abruptly printed upside down, and you have to flip the book to continue reading. On the surface, this gambit is an allusion to two other structures built ass-up: the fictional Castle Faggot and the real-life House Upside Down, the trick-mirror attraction Henry Roltair designed for the Pan-American Exposition, which makes a cameo here. Thematically, the book’s one-eighty dramatizes an inversion, a fall-down-the-rabbit-hole into a world of perverted nostalgia.

The mix of cartoons, sugary cereal, dollhouses, puppets, and wordplay evokes the arrested development that Freud and countless others considered intrinsic to homosexuality—a conceit central to McCormack’s novel. So, too, is the idea that gay men will gladly screw themselves to death: “All the faggots in the castle died because they wanted to be décor,” McCormack writes, adding, “What faggots did was to turn fucking into decorating. What faggots did was to turn decorating into fucking.” Here, the “little death” of orgasm is just another punchline: gay men sacrifice themselves for the sake of a tastefully appointed room. In other novels, such stereotypes and sexual fatalism could be misread as retrograde, a throwback to Larry Kramer’s AIDS-era pro-monogamy evangelism. In Castle Faggot, they’re more like rage alchemized into a liberatory self-deprecation. McCormack accepts trauma as the white noise of gay life. Besides, faggot is a humdrum insult when you have queers, caked in their own feces, hanging dead from chandeliers.

Midway through the book, McCormack himself appears as a teenage character (a device familiar from his 1996 novel Dark Rides). He’s mistakenly called “the Wizard,” but, as he informs his interlocutors, “My name’s Jonathon Derek McCormack . . . Mom and Dad call me Jon-D. My teachers call me Derek. My classmates call me fudge-packer. Or fruitcake. Or faggot. Or fag.” But he’s also a puppet, like everyone else in the scene. By implication, the puppet master is the real Derek McCormack, the cult writer in Toronto who has published all of these grisly books. The formerly bullied boy now calls the narrative shots. If readers are jonesing for empowerment, that’s as close as this novel comes. It’s McCormack’s version of the “it gets better” campaign. Only it doesn’t get better. It gets uglier and uglier, until you either slit your wrists or survive out of sheer vindictiveness.

Which brings us back to Tommy Kirk. In the early ’90s, he told Filmfax magazine, “I’m not ashamed of being gay, never have been, and never will be. For that I make no apologies. I have no animosity toward anybody because the truth is, I wrecked my own career.” That’s debatable, but it’s one way to live. As he kneeled on carpets to erase the stains of other people’s good times, I like to imagine he felt the very adult satisfaction of simply getting by.

Jeremy Lybarger is the features editor at the Poetry Foundation. He has written for the New Yorker, Art in America, the Paris Review, the Baffler, the Nation, and more.