Lake Micah

Lake Micah

“Uncle Sambo Wants You!”: Darius James’s satirical novel comes back into print.

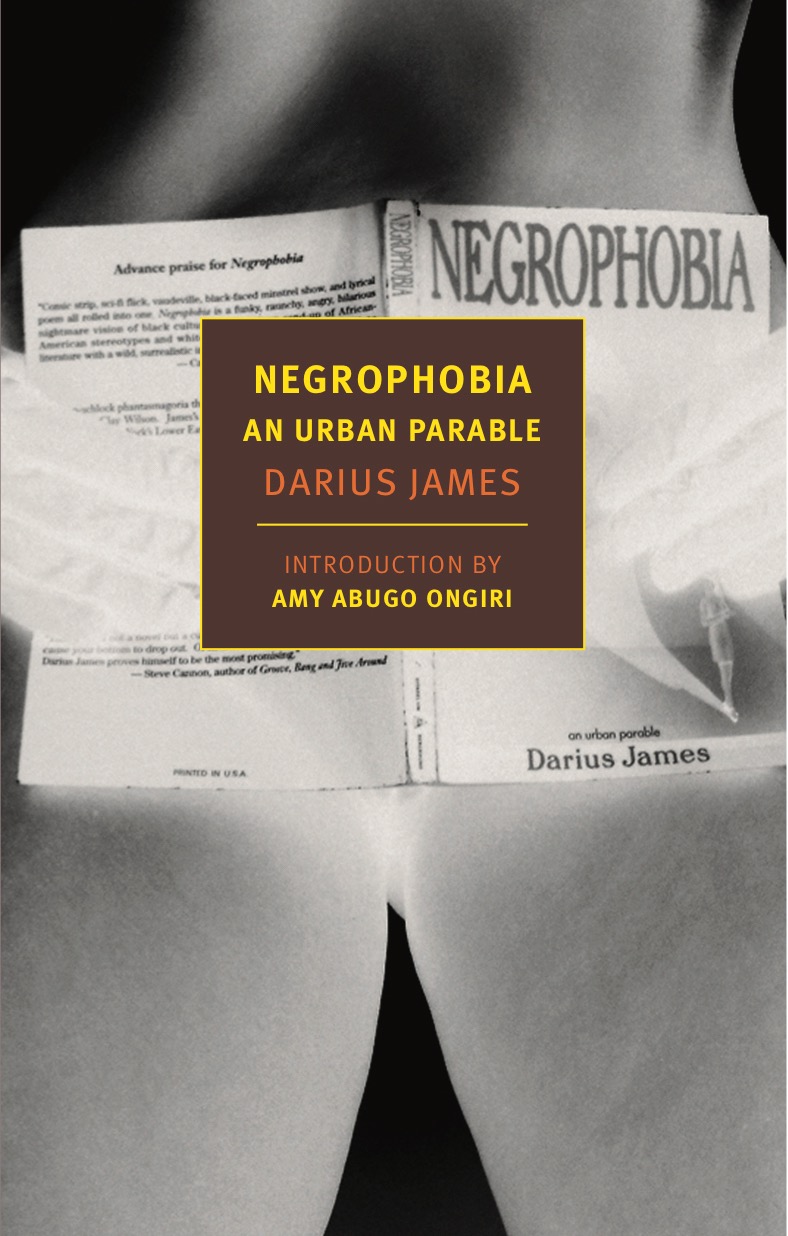

Negrophobia: An Urban Parable, by Darius James, New York Review Books, 174 pages, $14.95

• • •

Darius James, the trenchantly maladjusted author, filmmaker, and performance artist, has dipped in and out of view for the last quarter-century, his mutant texts causing a stir before going abruptly out of print. James himself once kept company with the likes of Kathy Acker and Dennis Cooper in New York’s thriving, fin-de-millénaire literary scene, but since the publication of 1995’s That’s Blaxploitation!: Roots of the Baadasssss ’Tude (Rated X by an All-Whyte Jury), he has become something of a lapsed and occasional writer. His work appears intermittently in anthologies, on websites, and at readings—where, on one occasion, he was ousted for urging spectators to “Put your dick where your mouth is,” among other advisories. But a New York Review Books reissue of Negrophobia: An Urban Parable, James’s 1992 novel-as-screenplay, has revived this first entry in his singular opus; and with a new preface to the book, James is gloriously revenant, too, along with his signature ethics of puckish vulgarity. Nota bene the front matter: “Negrophobia is a work of fiction. Every word is true. Fuck You. THE AUTHOR.” Fueled by such simmering fury, James’s “parable” thus emerges as the senseless lesson of a giddy antichrist.

Or else Satan himself. Indeed, the New York of Negrophobia can resemble Pandemonium, Milton’s coinage for the capital of Hell, in more than just its petty anarchy. Bubbles Brazil, the book’s young white protagonist, traverses a blighted metropolis, imagining herself accosted on all sides by a demoniac parade of ghoulish, Black visages. (In short, that’s the plot.) Mammies, burrheads, and other staple characters from a directory of American racist caricature populate her city, speaking a barely intelligible hybrid tongue—a fabricated pidgin of creole and Ebonics admixture. “We is no longa cullid,” a Hattie McDaniel–redolent housemaid explains.

“We is whatchoo calls Neo-African Americans—hostages misplaced in time, captives of a racist hist’ry ’n’ a oppressed peepus dissolvin’ in d’stomach acids of whyte amerika.”

True enough—I guess. More interesting is her idiosyncratic retribution for this sorry fact. Infuriated by Bubbles’s brazen racism and vacuous self-victimization (“I’m oppressed!” Bubbles says. “But you wouldn’t know anything about that. You were never white and pretty!”), the maid recites a voodoo incantation, cursing Bubbles to walk an earth peopled only by the hyper-stylized grotesqueries that Bubbles insists Black people already are. “An onrush of fragmented images, evoked in low lit eeriness”—so many niggas!—“stab Bubbles’ consciousness in quick succession, congealing into a cubist portrait of urban paranoia.” For the first time actually confronted with her worst fears, Bubbles shudders, and hyperventilates with terror.

This is the book’s ingenious satire, its arch irony and righteous revelation: now noxiously literalized, Bubbles’s Negrophobia—an exaggerating locution whose diluted essence one can detect in today’s “antiblackness”—proves itself self-inflicted, the result of paranoid imagination. Her hypnotic fugue is a variety of magical thinking, and her racist ideation, sustained and promoted by her “phobia,” has ensnared her as surely as it has the objects of her malignant sensibility. Hear the fearful timbre of her Ginsbergian howl, in which she enumerates her awful phantasmagoric visions:

Mindless angel-dusted darkies slobbering insane single syllables, flicking switchblades and flashing straightrazors. Hip-Hoppity jungle bunnies in brightly colored clothes, carrying large, loud radios we white wits call “Spadios,” who drank bubbling purple carbonates and ate fried pork rinds and bag after bag of dehydrated potato slices caked with orange dust. Crotch-clawin’ niggas who talked Deputy Dawg and shot dope. Saucer-lipped ragoons who called me the “Ozark Mountain She-Devil” and asked to feel my lunch money. Percussive porch monkeys who fart with their faces to a heavy-metal beat.

Panicky, exhaustive, breathless, this tirade typifies Bubbles’s condition, which the book’s screen directions diagnose as a “Negrophobic predicament.” The “predicament” here is conceptual; Bubbles’s Negrophobia was only ever, as scholar Lauren Berlant might suggest, a cruel optimism: beguiling and misbegotten—an impossible posture and ruinous to maintain.

Negrophobia could be the story of Bubbles’s path to this realization. “When I first gazed at my reflection in the bedroom mirror . . . there was no way to calculate the dimensions of my disease, the degree of my negrophobia,” she says, in the book’s final pages. Like Dante’s pilgrim, she stumbles through “concentric, ever-widening circles of darkness,” and confronts “the contents of my own mind in full . . . not knowing what waited in the wellsprings of my psyche, not knowing how I might transmogrify.” And she encounters along the way a motley crew of varying symbolic provenance—among others, Tar Baby, Black Muppets called “Buppets,” and Aunt Jemima ninja-acolytes. Seemingly, these rendezvous account for Bubbles’s moral metamorphosis, performing a sort of reeducating racial-exposure therapy. But then, to insist on this pilgrim’s progress would be to fall for Negrophobia’s grand, gratuitous prestidigitations.

In truth, James’s project is like that of his analogue, the artist Kara Walker, who has said about reading Negrophobia: “It was one of those good but rare occasions when I thought there might be one other person in the world that would get what I was doing.” Spelunking with none of the superstitions and fears that keep most others out, James steals into the unholy sepulcher of racist conceit, resurrecting with necromantic glee tabooed depictions of Black life—the coon and the pickaninny, baleful hieroglyphics—and enlisting them in his ludicrous, licentious schemes. (In her travels through the New York underworld, Bubbles happens upon a poster bearing the message: “UNCLE SAMBO WANTS YOU!” It sounds like the originating germ of James’s enterprise.) It’s a wily wont, a facility for the vandal’s pillaging appropriation of outlawed, discarded iconography. And it succeeds, the novel finally settling into a hybrid, anarchic work of grabby bricolage.

Yet the necessity or utility of it all is difficult to decide. One wonders why James rescues these garish totems: Is his aim recreation, or recuperation? Perhaps both? What’s evident is that he rejects the notion of disgraced historical artifact as untouchable curio, dusty and grave. His preference is to grasp it, a breakable plaything, and get it back into the showroom. Still, his ultimate philosophy is unclear. He has said that he “chose to reclaim racist imagery” because he finds “those images personally funny.” Well, and what else? He may derange the historical record, furnishing it with the gruesome embellishments it now embraced, now denied, but what, in the end, remains? Effigy or monument?

Maybe it’s wrong to ask. Negrophobia never strives for nobility, and its unnerving bastardizations of minstrelsy’s crude stock are a triumph in themselves. Darius James, liberated from the too-common expectation that Black writers be instructive (that is, pedantic), offers a shrug and a middle finger to all that: Fuck you.

Lake Micah edits at Simon & Schuster and is a freelance writer on literature and the arts.