Megan Milks

Megan Milks

In a literary biography, Chris Kraus tackles the life, work, and mythology of the cult countercultural writer.

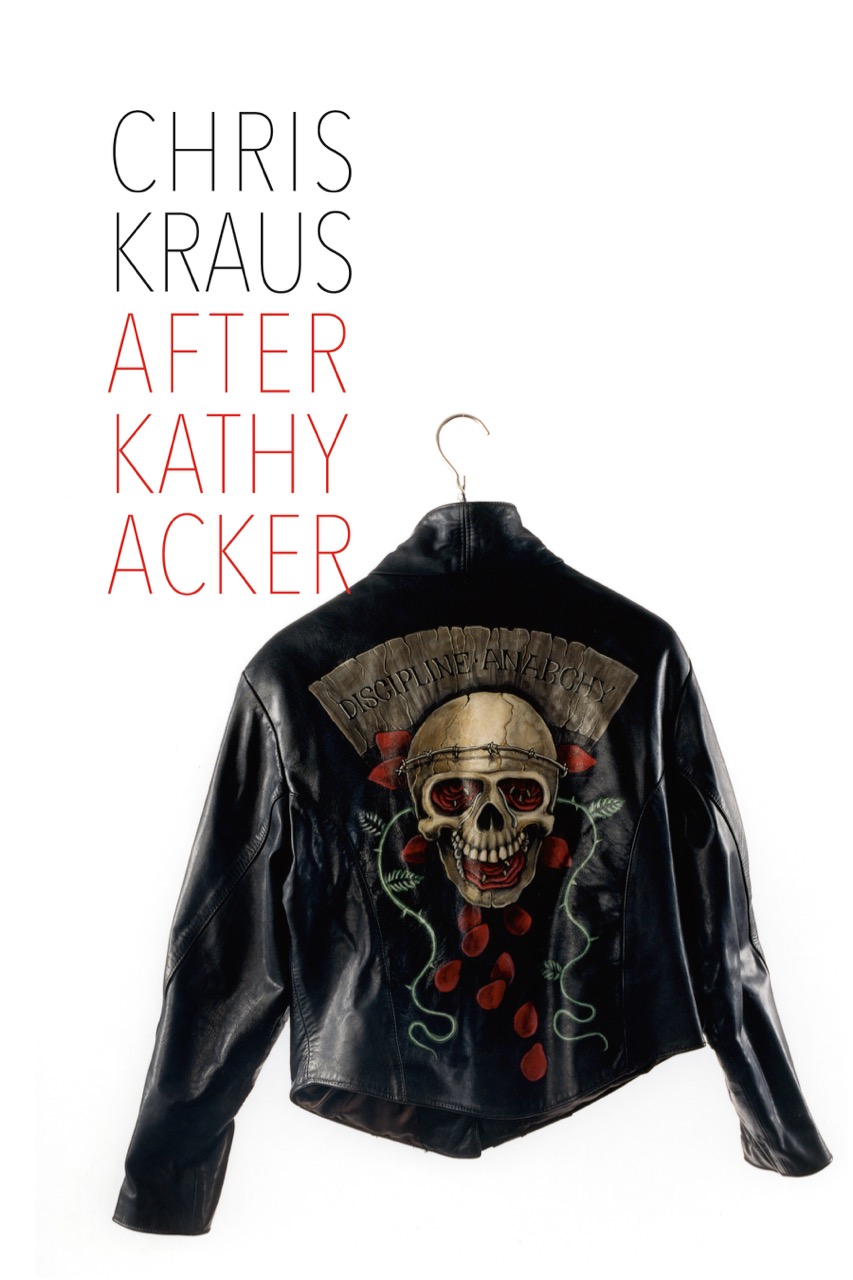

After Kathy Acker, by Chris Kraus, Semiotext(e), 345 pages, $24.95

• • •

Chris Kraus’s first novel, I Love Dick, was published the year of Kathy Acker’s untimely death from cancer at the age of fifty. A half-generation behind Acker, Kraus shares similar aesthetic and philosophical concerns and has inherited, to a certain extent, Acker’s status as cult avant-garde female author. I Love Dick is enjoying a revival thanks to Jill Soloway’s TV adaptation, and now Kraus has written the first authorized biography of Acker. With After Kathy Acker, Kraus is “after” Acker in multiple ways, at once under her influence and in pursuit of her life and legend.

Kraus moves fluidly between literary analysis, biographical history, cultural criticism, and abundant literary gossip to trace Acker’s formation as an artist and her deliberate self-construction into “Great Writer as Countercultural Hero”—the first woman, Kraus argues, to achieve this mantle. In novels like Blood and Guts in High School (1984) and Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream (1986), Acker combined avant-garde strategies with punk feminism to produce promiscuously intertextual yet compulsively readable prose. Though she won only one award during her life (a Pushcart Prize), she found significant fame as an underground icon.

In chapters devoted to loosely defined periods in Acker’s writing life, Kraus follows her subject from New York to San Diego to New York to San Diego to San Francisco to London and so on, chronicling her introduction to avant-garde methods via poet David Antin and his partner, the conceptual artist Eleanor Antin; her many affairs and infatuations; her multiple encounters with cancer; her legal trouble with Harold Robbins over his accusation that she plagiarized one of his novels; and her discoveries of bodybuilding, BDSM, and the Internet—all addressed in direct relation to how they enter or impact her work.

“Why shouldn’t writing be everything?” Acker asked in a letter to poet Bernadette Mayer in 1974. From early on, Acker was a graphomaniac: she wrote dutifully, obsessively, documenting her dreams, fantasies, and daily life in journals, notebooks, and diaries, and subsequently inserting this archive of female experience into those areas of literature and theory she felt had left it out. Poring over what’s left of Acker’s papers—at times the record drops off—to parse the gaps between her life and her work, Kraus offers a fascinating study of how Acker bent and exploited her life in her art. The book is a portrait of an “I” and the ways in which Acker mythologized it.

I bought that myth wholeheartedly. When I was twenty-six I got the pirate girl from the back of Acker’s novel Pussy, King of the Pirates (1996) tattooed on my shoulder. For some years, I was an insufferable Acker acolyte; friends would start shifting uncomfortably when I mentioned her name. Imagine my surprise to learn, via Kraus, of the many fabrications that made up her origin story. Acker’s claim, for example, to have moved across the country to study under Herbert Marcuse was a blatant lie. In fact, Kraus reveals, Acker never studied with Marcuse and most likely never met him. Kraus isn’t playing “gotcha” here so much as attending to the ways in which Acker constructed herself as an artist and intellectual: “Didn’t she do what all writers must do? Create a position from which to write?” Acker tweaked her biography repeatedly to fit the story she wanted to tell.

Throughout, Kraus balances this de-mythification of Acker’s life with a generous appraisal of her work. Her biography is particularly vivid when engaged in the latter project; indeed, this is among the best writing on writing I’ve read. Take, for instance, this exhilarated analysis of Acker’s punctuation tactics in Great Expectations (1982), her most elegiac novel: “The colon is used as a summoning . . . [it] functions as a slap, a jolt, an epinephrine shot that yanks the sentence—and by extension, us—from grief’s downward drift into the present time.” Speaking to Acker’s overall oeuvre, Kraus suggests the source of her work’s power is that insistent “I”: “Perhaps the greatest strength and weakness in all of Acker’s writing,” she contends, “lies in its exclusion of all viewpoints except for that of the narrator.”

Acker was, in many respects, a narcissist. While her self-obsessed impulses achieve profundity, transgressive valence, and, frequently, hilarity in her writing, they often overwhelmed her friends and contemporaries. In one of many anecdotes collected here, writer Barry Miles describes Acker as a terrible houseguest who was “not very aware of other people or their needs.” She took over the apartment’s common space with unwashed dishes, patchouli oil, and yoga, he remembers, and when his partner “ran screaming from the flat . . . Kathy was completely unaware that anything might be amiss.” But obliviousness can’t explain what seem like more deliberate aggressions directed at other women artists: writer Constance DeJong recalls Acker punishing her for outshining Acker at a reading they set up together. Composer Jill Kroesen wrote a song about her called, unsubtly, “Insecure Girlfriend Blues, or Don’t Steal My Boyfriend.”

The book is not just a Rolodex of writers and artists from the late-twentieth century—though that aspect in itself is a treat. With these interviews and anecdotes, Kraus adamantly places Acker within a dynamic social milieu, a milieu in which she herself participated. In what seems like an odd omission, Kraus leaves out any discussion of her own connections to Acker. The two writers certainly knew each other, but it’s unclear how well. Still, Kraus’s firsthand knowledge of the overlapping literary and art scenes with which Acker interacted makes for compelling cultural analysis.

As part of this analysis, Kraus takes pains to emphasize how Acker was, well, just like everyone else. Acker found the gym in the 1980s, Kraus writes, “like many downtown New York women”; she had a postmodern understanding of the self, “like many highly intelligent people.” A comment from artist Martha Rosler concludes the book—“I could’ve been Kathy. Kathy could’ve been me.” Ending here underscores the instability of identity that Acker’s work explores so thoroughly, while solidifying Kraus’s aim to read Acker’s life through a collective lens.

She may be underselling Acker’s particular genius in doing so. But Kraus is not interested in giving us an exceptional female genius. She gives us an “unlikable” female character instead: a captivating, vexing, contradictory artist who influenced and was influenced, who exuded power and vulnerability at once, who was part of a vibrant artistic ecology that alternately adored and rebuffed her, and who, above all else, left us far too soon.

Megan Milks is the author of Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, winner of the 2015 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award in Fiction and a Lambda Literary Award finalist, as well as three chapbooks, most recently The Feels, an exploration of fan fiction and affect. Milks is fiction editor at The Account, and editor of the books The &NOW Awards 3: The Best Innovative Writing, 2011–2013 and Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives.