Albert Mobilio

Albert Mobilio

What dreams (of things) may come: a survey at the Met presents 160 works by the enigmatic artist.

Man Ray: When Objects Dream, installation view. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

Man Ray: When Objects Dream, curated by Stephanie D’Alessandro and Stephen C. Pinson, with Micayla Bransfield, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through February 1, 2026

• • •

We dwell in a domain of stuff; it presses in upon us, absorbs our attention, facilitates nearly every action. Yet rarely do we seriously contemplate the gadgets we use as if they were extended limbs. Those mundane tools of daily life are too familiar to be truly seen. But the American-born artist and photographer Emmanuel Radnitzky, better known by his adopted moniker Man Ray, observed much to brood upon in the quotidian materials he found readily at hand. The Metropolitan Museum’s exhibition When Objects Dream is a generous survey, presenting 160 works, including many famous photographic portraits along with rarely seen sculptures and paintings. Three recently restored films from the 1920s—Retour à la raison (Return to Reason), Emak Bakia, and L’étoile de mer (The Starfish)—are particular revelations. The inclusion of Obstruction, a sculpture comprised of sixty-three wooden coat hangers suspended from the ceiling in pyramidal form, is one of many curatorial choices that illuminate Man Ray’s meticulously executed mission to transfigure the commonplace. Such pieces, set in several rooms around the main display, contextualize the eerily transformative pictures of ordinary items—a comb, gun, eggbeater, iron, wrench, screws, keys—that form the show’s main attraction.

Man Ray: When Objects Dream, installation view. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen. Pictured, center background, suspended from ceiling: Obstruction, 1920/1961.

Taking an iconoclastic cue from Surrealist and Dadaist confederates—André Breton, Jean Cocteau, Marcel Duchamp, and Francis Picabia—Man Ray sought to challenge accepted notions of artistic subjects and develop compositional methods that might offer fresh entry points to visual experience. To this end, he employed an updated version of the nineteenth-century photogram, which he dubbed the rayograph, that involves placing objects on or near sheets of light-sensitive paper to produce reversed silhouettes. These black-and-white images can resemble conventional photo negatives, but the process confers a distinctive element of dimensionality so that a bottle or light bulb seems to float in cloudy blackness.

Man Ray: When Objects Dream, installation view. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

Dim lighting enhances the oneiric mood of the rayographs, especially the 1922 portfolio of twelve rayographs titled Champs délicieux (Delicious Fields), on view in the first gallery, a collection that he described in terms both technical and transcendent: “Like the undisturbed ashes of an object consumed by flames these images are oxidized residues fixed by light and chemical elements of an experience, an adventure, not an experiment.” The shimmering depth of the individual untitled gelatin silver prints in this series captivates immediately; the viewer is drawn into a pictorial space that appears cosmological, as if we were gazing at depictions of the solar system rather than detritus likely pulled from drawers. (Indeed, a vitrine contains an array of tools and miscellaneous hardware from the artist’s studio.) In one image, a black comb, placed in sharp contrast to a sun-bright white ellipse, dominates the frame, each of its teeth precisely defined. Parallel to the comb is what looks like a woodworking implement, its pointed end bearing the marks of use. Around these items, less identifiable materials hover in the dark ether. The grouping, at once chaotic yet not without order, invites speculation as would an unfinished puzzle or enigmatic phantasm. In a 1934 monograph, poet Tristan Tzara wrote that rayographs were “projections surprised in transparence, by the light of tenderness, of objects that dream and talk in their sleep.”

Man Ray, Rayograph, 1925. Gelatin silver print, 19 15/16 × 15 13/16 inches. Courtesy MAH Musée d’art et d’histoire, City of Geneva. Photo: André Longchamp. © Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS) / ADAGP.

Decidedly more straightforward, the rayograph of a toy gun and a room key abstracts both. While recognizable, because they are shorn of particularizing detail, the photographer insists on their physical rather than practical or social reality (although the number thirty-seven on the key chain carries the suggestion of some secret intimacy). This revelation of an object’s essence brings to mind Heidegger’s notion of “thinging,” the act of a thing becoming itself in the world. Is this the adventure Man Ray aimed to engender: a kind of “becoming” intrinsic to the viewer’s perceptual act? Around the time of Champs délicieux’s publication, the poet Louis Aragon coined the term mouvement flou, “blurry movement,” to characterize the period between Dada and Surrealism. That “blurriness” manifests quite literally in photos that seek to capture motion, the slippery spirit of action. The subjects that populate another image from the portfolio can only be guessed at: cords or twine, a diaphanous piece of cloth, perhaps a vise or some kind of brace—but all convey the impression of movement, if not dance. Unlike the exacting delineation of the comb, these materials are rendered out of focus, gauzily suspended in dreamlike flight. Energy is being discharged, and the sensation is palpable.

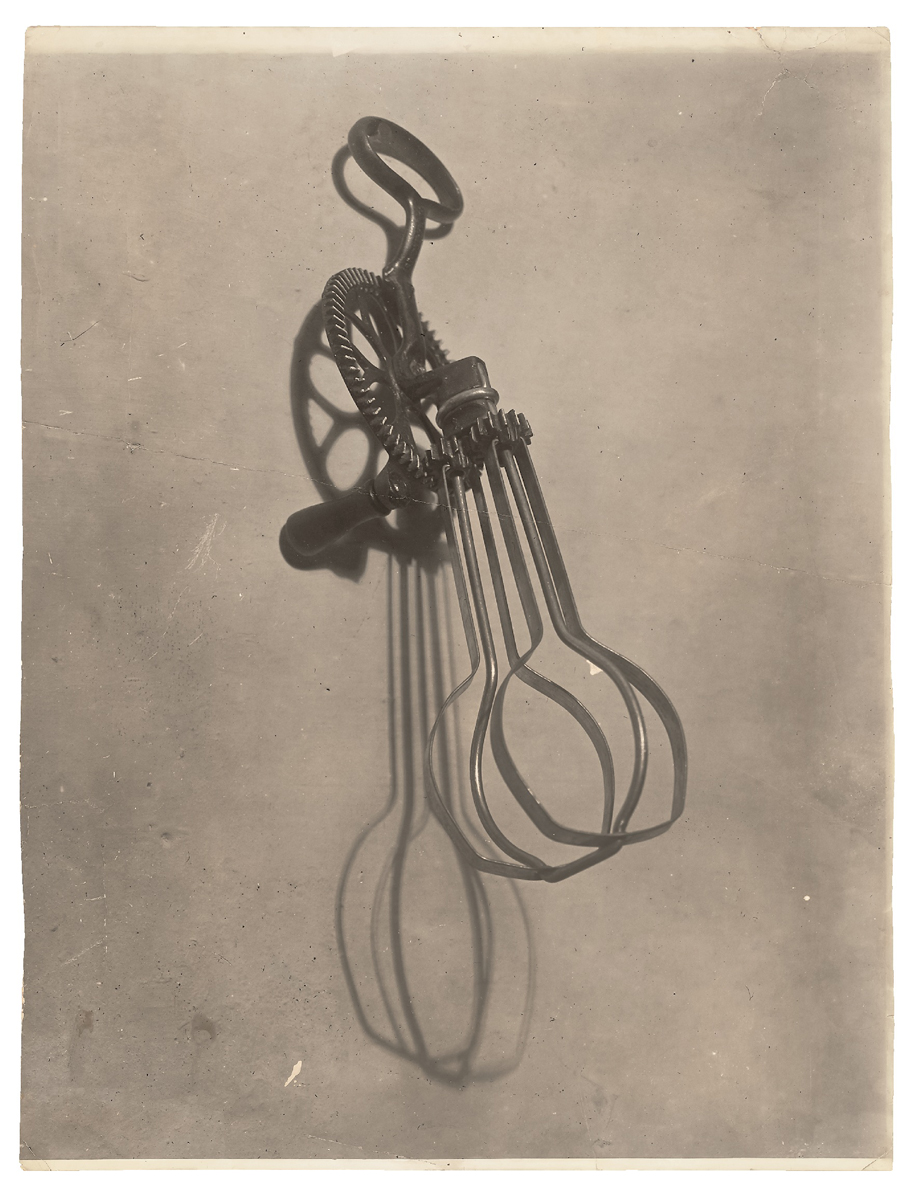

Man Ray, L’homme (Man), 1918–20. Gelatin silver print, 19 × 14 1/2 inches. Courtesy the Bluff Collection. Photo: Ben Blackwell. © Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS) / ADAGP.

Organized in a loose chronology, the show emphasizes thematic consistency: moving from room to room, viewers are immersed in a singular, if not obsessive, vision. Photos that precede the rayographs by a few years are no less dynamic. In L’homme (Man, 1918–20), a solitary eggbeater is set against a gray background in a typological manner comparable to that of Bernd and Hilla Becher. But this otherwise studious portrayal makes cunning use of shadow to double and distort the handle, gears, and whisks to create a kinetic effect—the device’s phantom twin appears to spin. Whatever interpretations emerge from the relation between the title and the mechanism, they are hardly obvious; Man Ray’s mischievous sensibility is sly and often veiled. Reading the two concave steel bowls in this photo’s companion shot, La femme (Woman, 1918–20), as alluding to breasts might be a sound guess, but that reading is complicated by the artist’s use of similar bowls situated above a handprint in Self-Portrait (1916).

Man Ray: When Objects Dream, installation view. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen. Pictured, center: Le violon d’Ingres, 1924.

This anthropomorphic impulse gets turned around in what is perhaps Man Ray’s best-known photo, Le violon d’Ingres (1924). (An original print sold for over 12 million dollars in 2022, but here it’s hardly given pride of place, set in a gallery along with several other celebrated images.) A portrait of his model and lover, Kiki de Montparnasse, offers a view of her nearly nude and seated figure from behind; two f-holes have been painted on her back to accentuate the correspondence between her torso’s curvature and that of a violin. Despite the overall humorous intent (the title also constitutes an insider jibe directed at the nineteenth-century Neoclassical painter), there couldn’t be a tidier example of what has come to be termed objectification, a female body transformed into an instrument.

However, Man Ray was typically keener on techniques of visual manipulation and their ability to produce defamiliarized and disconcerting images than on any attempt at actual portraiture. Close to Le violon d’Ingres are four successive pictures of Kiki. She is again nude and stands in the posture of Ingres’s painting La source; each photo, though, grows increasingly less distinct until the human figure becomes an abstract shape nearly subsumed by the surrounding dark. If bodies, as Man Ray depicts them, metamorphose into things, they are things arguably imbued with consciousness: things, in Heidegger’s sense, in the act of becoming. And, if objects dream, they likely dream as we do—about themselves.

Albert Mobilio is the author of five books of poetry: Beginning of the Hollow (forthcoming 2026), Same Faces (2020), Touch Wood (2011), Me with Animal Towering (2002), and The Geographics (1995). A book of fiction, Games and Stunts, appeared in 2016 and a selection of criticism, Reading Against Type, was just published.