Evan Moffitt

Evan Moffitt

A towering installation at MoMA embraces evasiveness.

Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen?, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Andy Romer.

Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen?, curated by Stuart Comer, Danielle A. Jackson, and Gee Wesley, with Veronika Molnar, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through January 30, 2020

• • •

It’s difficult to imagine a more challenging or overdetermined space than the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art. Soaring sixty feet high, the austere light well has tended to dwarf the artwork commissioned to fill it, at least until Adam Pendleton’s Who Is Queen? (2021). Three wooden balloon-frame structures, of the type used in American home construction and painted the same jet black as the Jean Nouvel–designed skyscraper next door, rise the full height of the vertical gallery and provide support for a series of spotlit paintings, as well as a screen upon which a trio of films is projected. A soundtrack of overlapping audio, referencing more than a hundred different sources, mixed in collaboration with Jace Clayton and featuring poetry by Amiri Baraka and music by Hahn Rowe, among others, spills into the adjacent galleries. It pauses intermittently while the films play: cinematic portraits of a 1968 protest encampment, an embattled Confederate monument, and the queer theorist Jack Halberstam, respectively. Much like its site, Pendleton’s installation is challenging and overdetermined; its disparate elements are unified only by their stark black-and-white palette and spotlights that slowly pan in each of the films, as if in vain pursuit of what the poet and philosopher Fred Moten has called “fugitive meaning.”

Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen?, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar.

Like much of Pendleton’s earlier work, Who Is Queen? is dizzying in its erudition; its references are cited in a curatorial didactic, extended wall labels, and a doorstop reader, available to purchase for $45. Pendleton’s refusal to elaborate his sources within the work itself—and, in some cases, his attempts to partially obscure those sources by layering them—aligns the piece with scholars such as Moten and Frank B. Wilderson III, who have repeatedly insisted on the right of Black subjects to not be understood. Most exegesis, in their view, is dependent upon the logic of white supremacy. This position poses a conundrum for MoMA, whose classificatory brand of art history is deeply indebted to enlightenment modes of thinking. Although Moten and Wilderson are both featured in the reader, neither the wall labels nor the didactic—the most publicly accessible information about Who Is Queen?—mention either of them or their theory of withholding meaning, which undergirds Pendleton’s work. There is thus a disconnect between the evasiveness of the installation and the museum’s reflex to clarify it with what ironically amounts to a partial explanation.

Adam Pendleton, So We Moved: A Portrait of Jack Halberstam, 2021 (still). Single-channel, black-and-white video, 30 minutes 58 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

“What do I believe in?” asks Halberstam in So We Moved: A Portrait of Jack Halberstam (2021), seemingly echoing a question from Pendleton, who follows the gender-studies professor as he walks through a park, dives into a swimming pool, and cycles around Lower Manhattan. “I believe that we live in a pretty shitty world,” he replies, “and that there’s never been a better time to figure out how to unmake this world, and we need new political tools to do so.” The comment links Halberstam—who has theorized the ways queer and transgender subjects fail to make sense in conventional society—to Moten, who (along with Stefano Harney) proposed the concept of the fugitive, on the run from the sense-making world of white racism, in The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (2013). At just over thirty minutes, So We Moved is the longest of Pendleton’s three films. It’s also the least withholding component of the exhibition. Although the slickness of its black-and-white, slow-motion footage sometimes recalls an ad for American Express, the film offers an intimate and relatable portrayal of a scholarly figure who might otherwise seem inaccessible to most viewers. Halberstam’s fears are our fears, his hopes our hopes. When he’s shown briefly speaking to one of his classes about reading “gender as a text and as a genre,” and the ways it is always written through perceptions of race, the film carefully adjudicates the candid and theoretical, the personal and political, which for Halberstam—who is transgender—are never truly separable.

Adam Pendleton, Notes on the Robert E. Lee Monument, Richmond VA (figure), 2021 (still). Single-channel, black-and-white video, 9 minutes. Courtesy the artist.

So We Moved is reminiscent of Pendleton’s earlier cinematic portraits of Yvonne Rainer (Just Back from Los Angeles, 2016–17) and Ishmael Houston-Jones (Ishmael in the Garden, 2018). The other two videos in Who Is Queen? are more abstract: in Notes on the Robert E. Lee Monument, Richmond, VA (figure) (2021), Pendleton’s camera circles the titular monument, which was covered in graffiti during 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstrations calling for its removal. In nocturnal shots, we’re granted partial views of messages like “ACAB” and “I Can’t Breathe” in sharp, roving beams of light. It’s a gesture more violent than illuminating, resembling a cop’s searchlight or a sniper’s eye. In Notes on Resurrection City (2021), pans of the Lee Monument have been spliced together with archival footage and photography of Resurrection City—an encampment that occupied the National Mall in Washington, DC, for six weeks during the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign. Resurrection City was erected shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and violently cleared by Capitol Police; its invocation here alongside the marks of last year’s Black Lives Matter protests may be intended to underscore the cyclical nature of Black Americans’ fight for basic dignity. But these images are presented without narration and in nonlinear order, so once again viewers must consult the reader for clarifying context.

Adam Pendleton, Notes on Resurrection City, 2021 (still). Single-channel, black-and-white video, 15 minutes 36 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

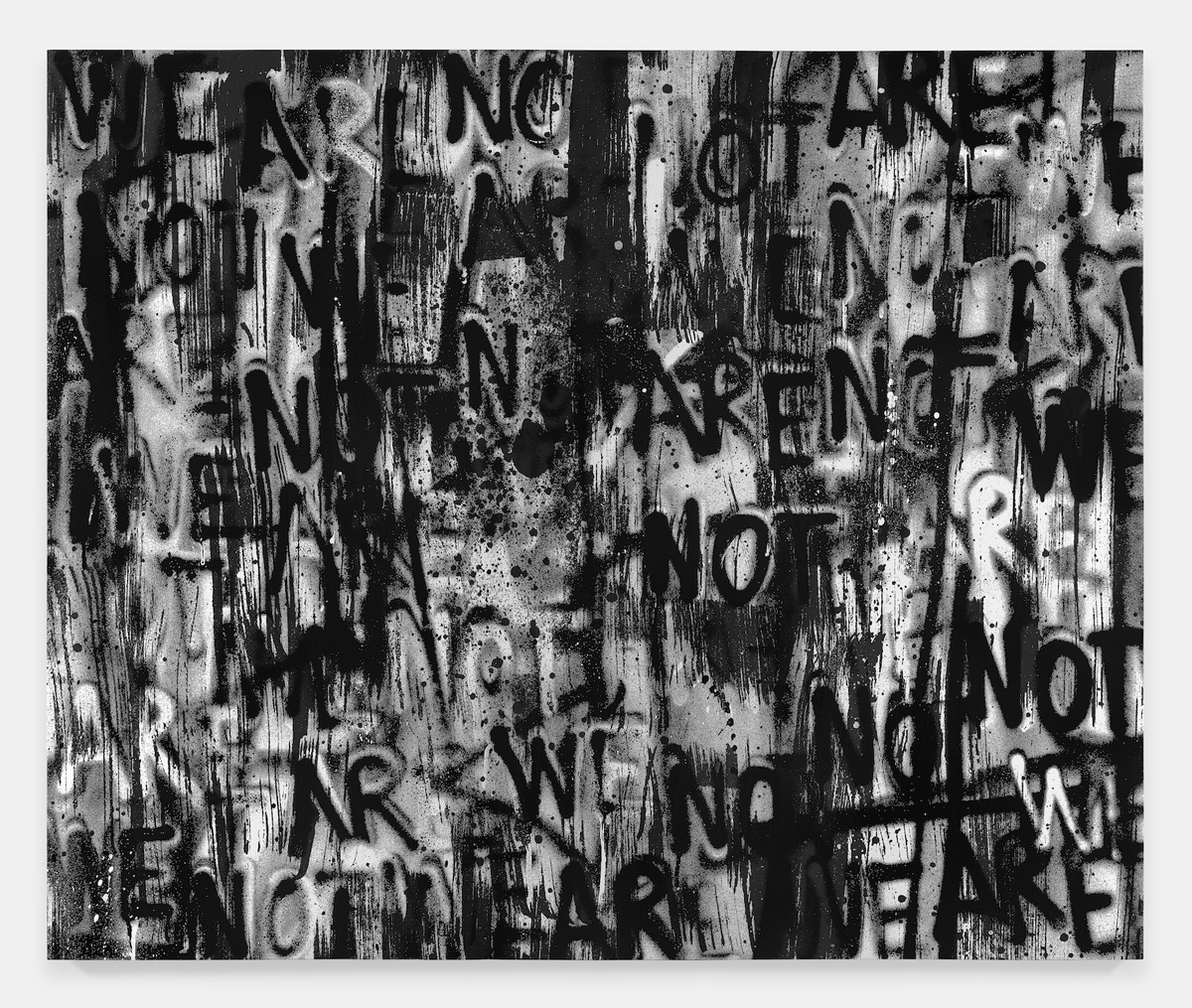

The paintings, meanwhile, adopt this abstract sensibility less effectively. Words in black on white grounds, resembling the graffiti on the Lee monument, are spray-painted, photographed, and then printed in layers, until they become almost totally illegible. In a conversation with curators Stuart Comer, Adrienne Edwards, Danielle A. Jackson, and writer Lynne Tillman included in the reader, Pendleton remarked that “the marks and slippages that accumulate in my paintings . . . are the refusal to be . . . an addressable subject, a speaking and communicating subject, and in some ways a productive subject.” The works’ insistent flatness, however, makes the words and gestures occluding them appear as unitary images. The eye doesn’t read them as acts of refusal, or even as actions at all, but rather as graphical white noise. Mounted at varying heights on the scaffolding, they look like digitally rendered set decoration. Pendleton’s fugitive “slippages,” so well captured by the structural breaks of cinematic montage, are almost entirely absent from smooth wooden and paper surfaces lacking real painterly marks. Given Pendleton’s prolific publishing output, it’s unsurprising that these paintings look much better in print than they do in person.

Adam Pendleton, Untitled (WE ARE NOT), 2021. Silkscreen ink on canvas, 120 × 144 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

“I think Queen, in its entirety, is about a refusal to be understood,” Pendleton told the curators, expressing his hope that the project would “overwhelm the Museum—and pose questions about what it can and cannot do.” By embracing incoherence, Pendleton can write off audience confusion as a measure of his work’s success, and by rejecting the principles of critique, his work can become impervious to criticism. However, Who Is Queen? challenges MoMA to host a set of ideas that are fundamentally incompatible with the museum’s dialectical view of history (despite the recent efforts of MoMA curators, in their rehang of its permanent collection, to abandon some long-held categorical biases). MoMA has assumed the self-congratulatory position of having elevated Pendleton’s charged political imagery without fully acknowledging his project’s theoretical implications. More than anything, this disjuncture reveals what our institutions cannot do. It compels us to break and remake them.

Evan Moffitt is a writer and critic based in New York. His work appears often in frieze, where until recently he was senior editor, as well as Aperture, Art in America, Art Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and the White Review. He is currently developing a podcast about the travel histories of artworks.