David O’Neill

David O’Neill

An exhibition of the writer, artist, and activist’s Rimbaud photo series invites identification even as it repels interpretation.

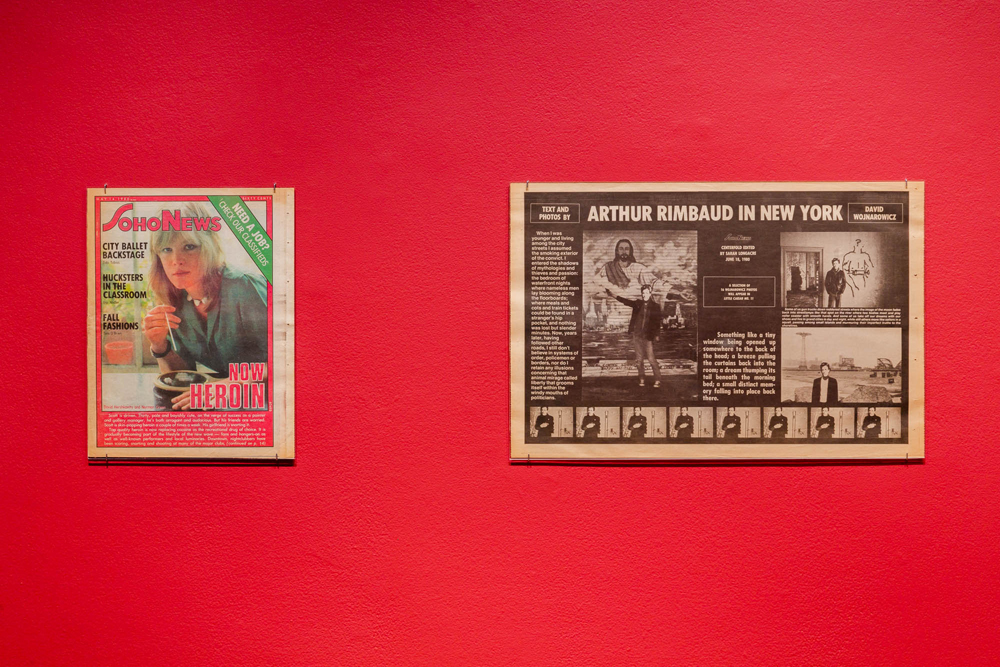

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, installation view. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Daniel Terna.

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, curated by Antonio Sergio Bessa, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, 26 Wooster Street, New York City, through January 18, 2026

• • •

“Our conversations were rarely trivial.” —Marguerite Van Cook on David Wojnarowicz

David, I’m talking to you again. It’s Wojnarowicz season in New York. Happily, this happens every few years. These days, you are remembered as a writer and visual artist. But just as often, you’re talked about in terms of culture wars and censorship. The right continues to use queer and trans artists as cannon fodder—perhaps more now than when you were alive, if you can believe it. I’ve been thinking about the line that caused so much trouble in 1989; you called a Catholic cardinal a “fat cannibal from that house of walking swastikas.” There are more fatuous fascists to contend with in 2025, and we’re still inspired by your outrage and courage. The last time we “spoke,” it was the summer of 2018, when your Whitney Museum retrospective, History Keeps Me Awake at Night, had inaugurated another Woj season. I don’t know whether you’d be honored or chagrined to know that you’ve only gotten more popular since your death in 1992. As an artist of misfit-centric egalitarianism and disaffiliation from a diseased society, you never wanted “fans,” yet here we are, calling you by your first name, trading your words and your art on long evenings lit up with Big Soulmate Energy.

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, installation view. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Daniel Terna.

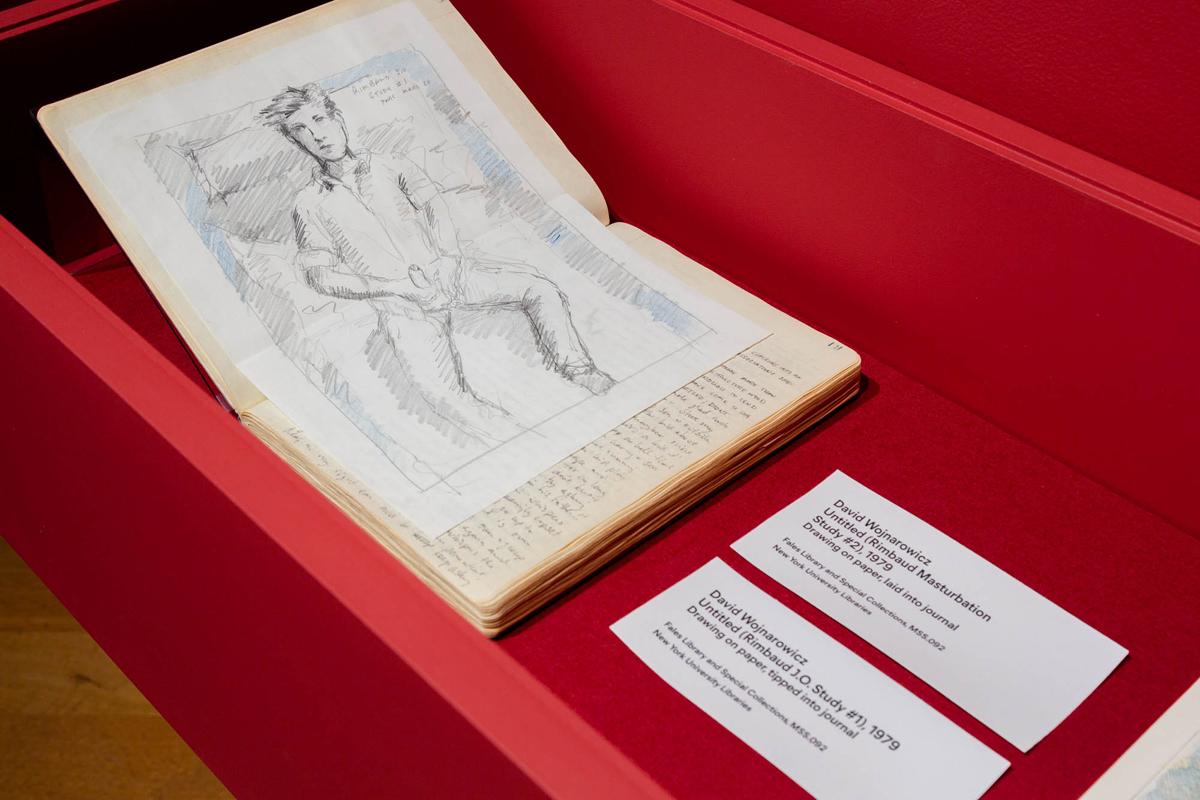

There’s a new exhibition, David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, curated by Antonio Sergio Bessa at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art and featuring an impressively expanded restaging of your earliest foray into visual art. You were once embarrassed by, in your word, the “naivete” of the Rimbaud works (1978–79), for which your friends posed all over the city in a homemade mask of the poet that you copied from the New Directions paperback of Illuminations. Today, the naivete is appealing, and we romanticize the pre-AIDS era of these photos. We glamorize the “Fear City” years of New York before the epidemic, sex on the bombed-out piers and starving artists in lofts that not even celebrities can afford now.

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, installation view. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Daniel Terna.

Speaking of celebrity, I tried to buy a T-shirt of the Rimbaud mask for fifty dollars from the museum, but it had sold out immediately, perhaps because we get three renegade artists in one: Rimbaud (who posed as a queer teen poet), Ray Johnson (who designed the book cover), and you, David (who copied the cover at your short-lived ad-agency job). What I’m saying is that people fucking love this show. The images are guileless and canny queer interventions in a hostile city called “home” by the friends—Brian Butterick, John Hall—wearing the mask in the subway, at the piers, in Times Square, in the meatpacking district: the places you hustled, suffered, and fugitively captured in art. We even get the dreamy Jean Pierre Delage as Rimbaud—the French fantasy come to life—at an abandoned Coney Island. Maybe people love the images because you were in love with Jean Pierre when you took them.

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, installation view. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Daniel Terna.

Judging by the two-page script from your archives, it seems the series was supposed to be a story: the poet arrives in the city and eventually overdoses on heroin. But that never panned out after nearly five hundred pictures. I meant to ask whether you ran out of money or just lost interest in this conceit. The lack of an overt narrative invites viewers to ponder the most important parallel between your life and Rimbaud’s—how both of you, as your biographer Cynthia Carr pointed out, “tried to wring visionary work out of suffering.” You might eschew this theory, this history, or bend it to your will. Still, viewers may want some context here. What would you want them to know? That 1979 is when you discovered the piers? That you had seen Ernest Pignon-Ernest’s posters of Rimbaud in a leather jacket plastered everywhere on your first trip to Paris? I’ve read many analyses—from Carr, Anna Vitale, Bessa, et al.—but I’m not sure I know what the series is actually about. The historical parallels explain little to me. And I hear you quoting Rimbaud’s line, “Je est un autre”—I is an other. You and the poet both invite identification as you continuously repel interpretation.

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, installation view. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Daniel Terna.

I do think you were kind of joking. You’re funnier than most people give you credit for, and I understand why that comedy is hard to see. You’re now a metonym of the social trauma of AIDS and an artist who helps us grieve the still-ongoing catastrophe of right-wing violence, whether it’s carried out through public policy or personal attack. How that mourning is expressed depends on who is looking and which part of your art and life they focus on. I focus on dark comedy, and when I grieve, I also kid. The Rimbaud photos seem irreverent, joyful even, and I don’t think that’s my nostalgia talking. A man in a paper Rimbaud mask peeing on the piers is a riot. Is this really a conversation about the power of pranking in unforgivable times?

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, installation view. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Daniel Terna.

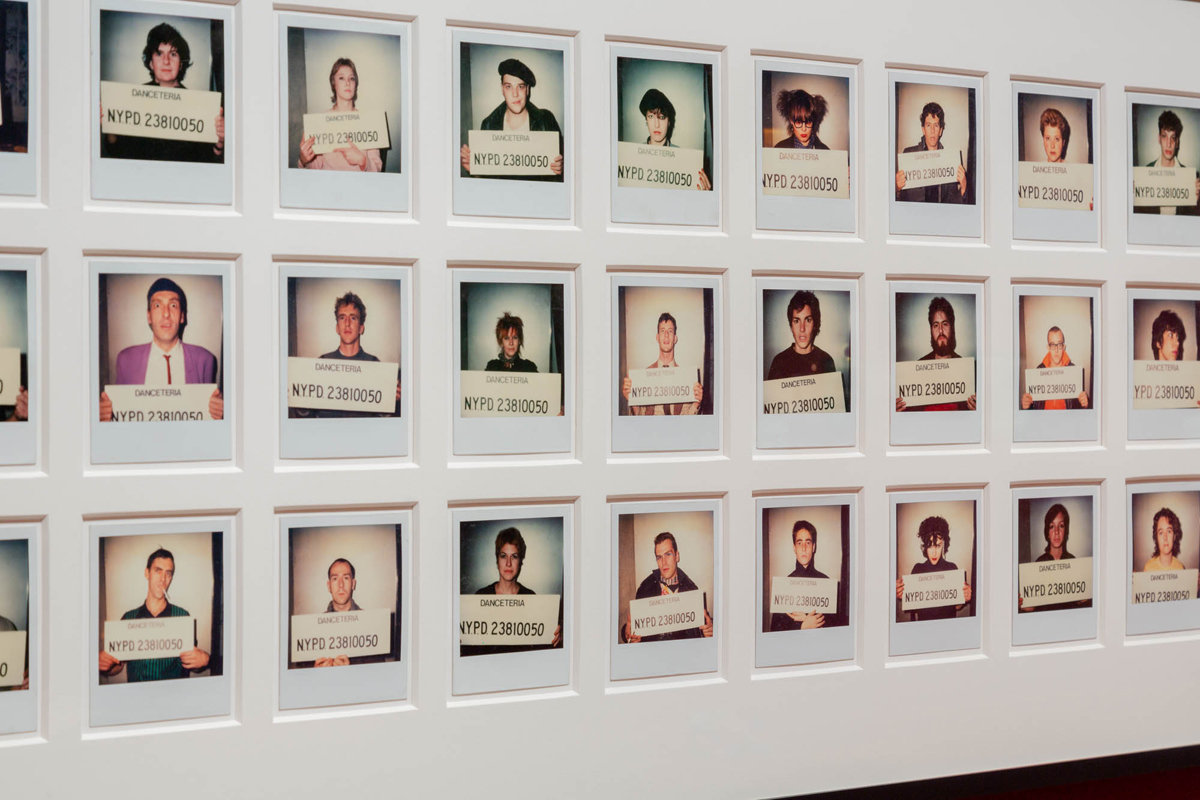

They pulled out all the stops for the show: Rimbaud images from the original 1990 photo set (you were always bad with dates, so I’ll remind you that was the first time the pics were exhibited, ten years after they originally appeared in SoHo News and Dennis Cooper’s Little Caesar), the more complete series from a 2004 P·P·O·W Gallery show, and thirty-two test prints. And archival treasures abound—your Polaroids from Danceteria (I love that you worked with Keith Haring and Zoe Leonard there, and how much you hated it), zines, contact sheets, letters, sketches, and so much more. You’d be floored by how lovingly your kindred spirits and early champions have kept your legacy going. The catalog’s acknowledgments page runs to dozens of names, all of whom carry your volatile openheartedness and fury at a fucked-up and beautiful world. And the book is a scholarly feat of the kind most galleries don’t bother with these days: Bessa’s insightful essay placing the series in conversation with artists from Vito Acconci to Sophie Calle; Nicholas Martin’s deep look at what Rimbaud meant to downtown artists; smart contributions from writers including Vitale, Craig Dworkin, Fiona Anderson, and more. Most movingly, Marguerite Van Cook recalls conversations with you, which, unlike mine, happened in the earthly realm.

David Wojnarowicz: Arthur Rimbaud in New York, installation view. Courtesy Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Daniel Terna.

Things feel so heavy these days. I know what you’d say: “Even in the face of something like gravity, one can jump at least three or four feet in the air and even though gravity will drag us back to the earth again, it is in the moment we are three or four feet in the air that we experience true freedom.” We all feel lighter in your presence.

David O’Neill is a senior editor of Bookforum and the coeditor, with Lisa Darms, of Weight of the Earth: The Tape Journals of David Wojnarowicz.