Nick Pinkerton

Nick Pinkerton

In a retrospective of films made over the course of five decades, a polyphonic portrayal of voices across class systems.

Anne Raitt as Sylvia in Bleak Moments. Courtesy Janus Films.

“Human Conditions: The Films of Mike Leigh,” Film at Lincoln Center, New York City, through June 8, 2022

• • •

It’s been said that you can find traces of everything a filmmaker will ever do or try to do in their first feature, and that every movie that follows consists of refinements and revisions of that initial creative splurge. This particular “rule” doesn’t readily apply to many debut films—the vagaries of art tend to frustrate catchalls and formulas—but Mike Leigh’s 1971 Bleak Moments, made when he was only in his late twenties and showing as part of Film at Lincoln Center’s two-week retrospective devoted to the director, offers a compelling argument in its favor.

Almost everything that makes Leigh’s films unique can be found in this oh-so-aptly-titled character study, which depicts the dimly desperate life of Sylvia (Anne Raitt), an office worker living in South London, and the people who drift into her orbit. Among them is an agonizingly shy, hippieish young man, played by Mike Bradwell, who obviously pines for Sylvia but can barely string together a coherent sentence in her presence. You can draw a straight line from Bradwell’s tormented failures of self-expression to the demented, drunken blathering of Mark Benton’s character in Leigh’s Career Girls (1997) or the gruff stammering of Timothy Spall playing the title role in Mr. Turner (2014), but it’s wrong to say that Leigh, whose films feature more than a few showboat extemporaneous speakers, particularly fetishizes inarticulacy.

Timothy Spall as J. M. W. Turner in Mr. Turner. Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics.

Leigh’s films are a catalog of wildly different and mostly English regional voices, united by a consistent fascination with the peculiarities of speech and how language serves as a marker of class, as a means of revelation and concealment of character, and, sometimes, as a weapon. (Leigh’s last theatrical film to date, 2018’s Peterloo, which depicts the lead-up to the 1819 Peterloo Massacre and the massacre itself and was appallingly ill-served by American distributor Amazon Studios, is a study in how the accumulated weight of words can gradually, inexorably tip the balance of events toward violence.)

Still from Peterloo. Courtesy Shutterstock.

Much of what’s regarded as distinctive and distinguished in screenwriting involves burdening a variety of characters with the same readily identifiable voice—that of the screenwriter. (Aaron Sorkin is the most prominent example of this phenomenon, though there are other less irritating ones.) The array of discrete, unique voices heard in Leigh’s films can be attributed to his unusual working method, already refined by the time of Bleak Moments, originally written for the stage and performed at London’s Open Space Theatre. Leigh’s films achieve a polyphony beyond the capacities of any single writer because Leigh is less a writer, limited by the boundaries of his own vocabulary and imagination, than an acute listener and editor.

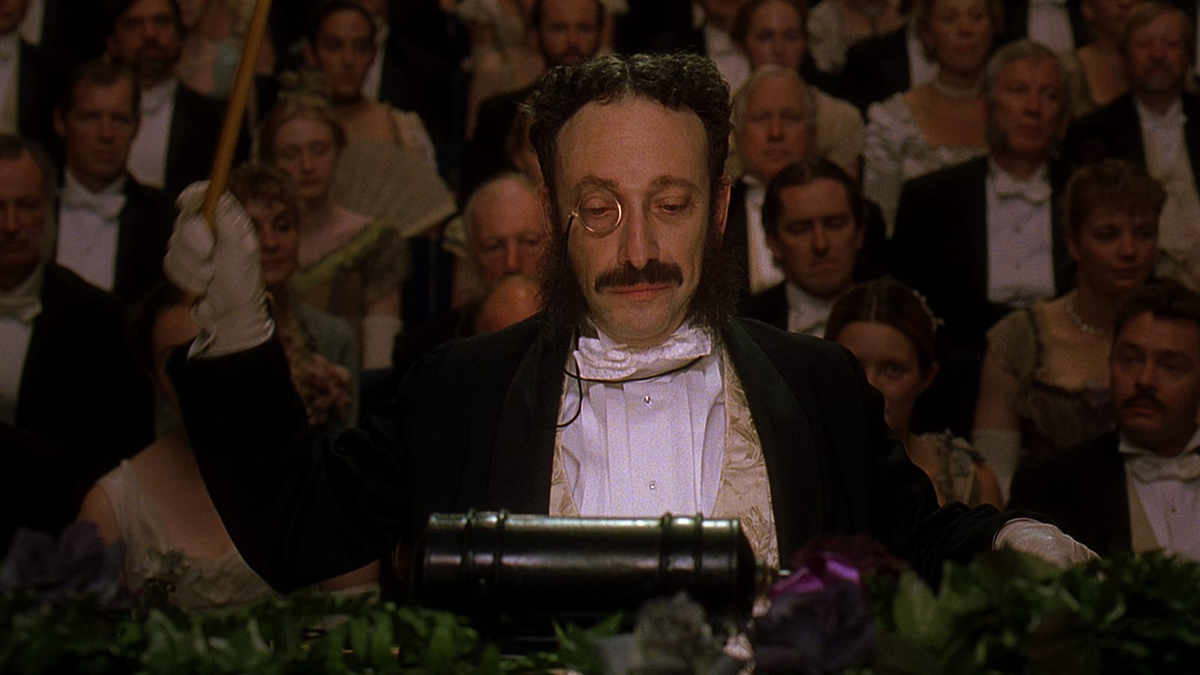

Allan Corduner as Arthur Sullivan in Topsy-Turvy. Courtesy Criterion.

Branded by an early encounter with John Cassavetes’s Shadows (1959), which he saw shortly after his arrival in London from Manchester to study acting at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, Leigh developed a process somewhere between that of Cassavetes—constructing scripts through extensive pre-production improvisation sessions—and the almost totally unpremeditated, camera’s-rolling spontaneous riffings being turned out in the 1960s by Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, and the Factory superstars. Then as now, Leigh initiated projects based on little more than a glimmer of a premise, building up dialogue and plot in collaboration with his actors, performing in character and bringing their own verbal idiosyncrasies to the parts. Leigh’s films based on historical events and predetermined outcomes—Mr. Turner, Peterloo, and Topsy-Turvy (1999), all of which play at Lincoln Center—do their due diligence regarding known facts and dates, but were made in a spirit of freedom and receptiveness to the happy accident that gives them a sense of in-the-moment spontaneity rarely found in the corseted period picture. His original stories are pure leaps into the void, often discovered in the course of shooting; Leigh has said he didn’t decide on an ending for his 1993 Naked until a couple of days before production was slated to wrap.

Having seen Naked perhaps a dozen times, I can’t recall the exact details of that ending, but this isn’t necessarily a demerit. Beginnings and endings are practical necessities imposed by a temporal narrative art like cinema. Leigh is no slouch as a “storyteller”—a fetish word of screenwriting labs—but what sets his films apart from the ones those labs leave their stamp on is the feeling they convey of life as taken by surprise, not as bent to obey the almighty three-act structure.

David Thewlis as Johnny in Naked. Courtesy Criterion.

Naked gives us its central character, Johnny, at a dramatically propitious point of crisis, fleeing down the M1 in a stolen car following a bout of rough sex in a Manchester alleyway that appears to have gone beyond the boundaries of consent, tweaking while seeking an ex-girlfriend in London to badger relentlessly. But because David Thewlis so entirely inhabits the part of this lacerating working-class wit—a character that the actor was instrumental in creating—with a relentless, jabberjaw amphetamine delivery, one can imagine Johnny’s entire (sad) history and (dark) future beyond what the film shows. Thewlis’s Johnny is larger than Naked; he seems a dangerous natural phenomenon fleetingly glimpsed in the wild rather than a convenient, makeshift, disposable contrivance engineered to serve a single, specific dramatic purpose and be binned once that job is done. The movie stops, but Johnny won’t be put away. So many characters in Leigh’s films—those played by the sublime Katrin Cartlidge in Naked and Career Girls, for example—have the same noisy restlessness; they refuse to leave you alone after curtain call.

Lynda Steadman as Annie and Katrin Cartlidge as Hannah in Career Girls. Courtesy Janus Films.

Movies use characters as pawns all the time, and in life people are constantly treated with the same cavalier disregard, as replaceable parts. Leigh’s filmography, taken as a whole, makes an impassioned argument that we deserve better from both cinema and life. It also offers a chronicle of the dismantling of Britain’s postwar commonweal consensus—not from a pretentious, prescriptive, top-down perspective, but from a point of view grounded in an earnest interest in and affection for human beings and how they’ve responded to, or failed to respond to, times that have changed without their consent.

Pam Ferris as Mavis, Jeffrey Robert as Frank, and Tim Roth as Colin in Meantime. Courtesy Janus Films.

When Leigh’s films indulge in cartoonish class grotesquerie—the broken working-class yobs of Meantime (1983); the gloating moneyed cretins of Naked and A Sense of History (1992)—it doesn’t seem perfunctory, doctrinaire, or hectoring, just a matter of faithful reportage. His films seek not to denigrate people on the basis of class, but show how people have been denigrated by the class system. As an acute, aghast reporter on the English scene, Leigh belongs to an elite company that includes William Hogarth, Martin Parr, and Mark E. Smith. His horror at how he sees his compatriots being forced to live is unmistakable. Also unmistakable is that a horror so profound could only be born of love.

Nick Pinkerton is the author of the book Goodbye, Dragon Inn, available from Fireflies Press as part of its Decadent Editions series. His writing on cinematic esoterica can be found at nickpinkerton.substack.com, among other venues.