Yasmina Price

Yasmina Price

Anti-colonialism, feminism, and Marxism abound in a retrospective of the Senegalese filmmaker’s oeuvre.

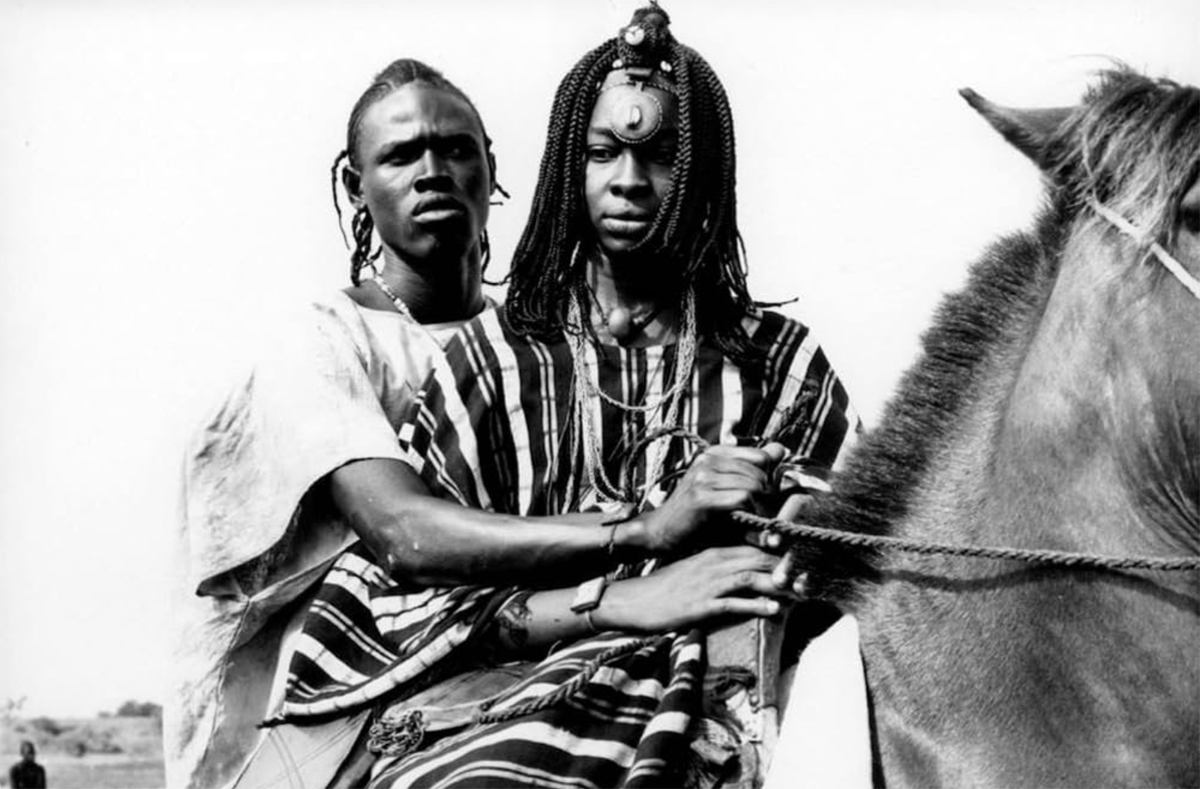

Tabata Ndiaye as Princess Dior Yacine in Ceddo. Courtesy Film Forum.

“Sembène,” Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City, through September 21, 2023

• • •

Ousmane Sembène the filmmaker was fashioned out of Ousmane Sembène the writer, formerly Ousmane Sembène the mechanic, carpenter, factory worker, longshoreman, and militant trade unionist. Although the Senegalese artist (1923–2007) is often too efficiently packaged as the social-realist “Father of African Cinema,” his contributions to the hard-won emergence and dynamic maturation of filmmaking on the continent were far more significant than reductive categorizations and exhausted patriarchal hyperboles suggest. A founding member of the Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI), he was, if anything, one of the many uncles of African cinema, a cohort anchored in a collective commitment to film in service of African political, cultural, and economic liberation.

A highlight of Film Forum’s retrospective is Sembène’s virtuosic 1970s trio, all screening in fresh 4K restorations: Emitaï (1971), Xala (1975), and Ceddo (1977). Crucially, they were preceded by the watershed Mandabi (1968)—his second feature, following the equally monumental La noire de . . . (1966)—which marked his turn away from pernicious French financial support and toward shooting in African languages. Shaped by a rejection of both financial dependence and linguistic paternalism, the films made during this prolific decade cemented a clearer cinematic alignment with his Pan-African Marxist views. The 1970s trifecta encompasses anti-colonial resistance, postcolonial satire, and historical epic, distilling both his range and political consistency.

Still from Emitaï. Courtesy Film Forum.

Something of a feminist thread runs through Sembène’s body of work, finding one of its more ambivalent but also more politically robust expressions in Emitaï. The film chronicles a gendered act of resistance by a largely Diola community in the Casamance region of southern Senegal, leveled against the French colonial forces’ extractive taxation demands and forced army conscriptions during World War II. Emitaï is structured around men’s chatty inaction and women’s mute activity. The Diola men are situated sitting at the foot of a tree, their palaver about the community’s loss of rice and sons, their sustenance and survival, seemingly interminable. The Diola women, silent save for their songs, are introduced in the midst of agricultural labor and—catalyzing the film’s dramatic unfolding—take on a stealth operation by hiding the rice stores from the French under cover of a bruise-blue night.

Still from Emitaï. Courtesy Film Forum.

Flipping a gendered cliché that equates men with action and women with talk, Sembène was one of the rare filmmakers to acknowledge and represent the importance of African women as political agents and historical actors. Equally notable is how the Diola women, alongside the men who also participate in Emitaï’s stunning final confrontation, form a collective insurgent subject. Sembène specifically sought to reauthorize a people’s anti-colonial history, hailing the masses rather than singular leaders. Sound is vital to this mission. Throughout, the Diola’s communal songs and instrumental music collide with the French colonial anthem. When Sembène makes a cameo (a charming recurrence across his filmography), he appears as a soldier mocking the farce of the French military’s abrupt shift from a song dedicated to Maréchal Pétain to one for Charles de Gaulle—a two-dimensional turnover literalized by a poster switch-up, and inconsequential for unchangeably colonized Senegal.

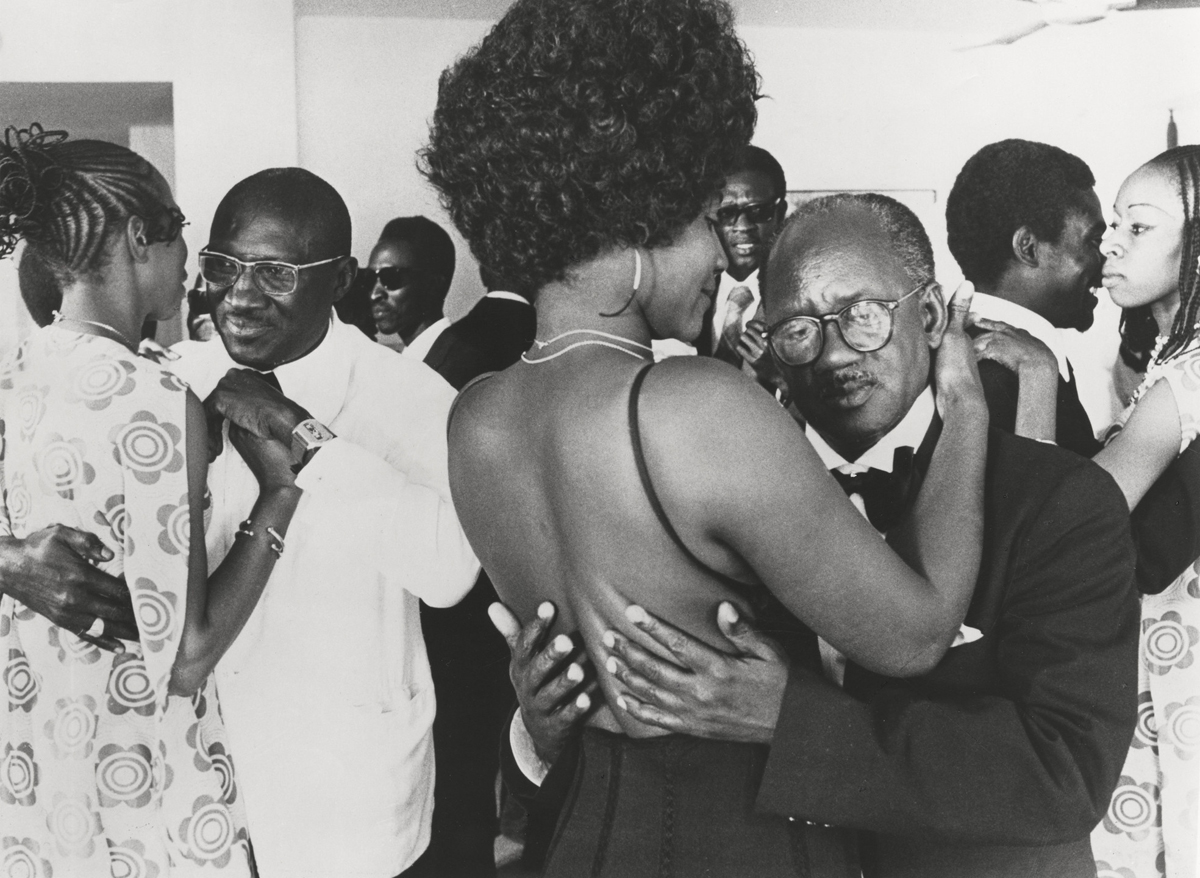

Younouss Seye as El Hadji’s second wife Oumi and Thierno Leye as El Hadji Abdou Kader Beye in Xala. Courtesy Film Forum.

Certifying Sembène as a maestro of intricately dense montage, reflecting the influence of his film training in the Soviet Union, Xala (1975) displays another elegantly politicized use of sound. Based on his 1973 novel of the same name, Xala, a box-office triumph at home, is a satirical indictment of the corrupt neocolonial Senegalese bourgeoisie, told through the fall of wealthy businessman El Hadji Abdou Kader Beye as a regrettably timed curse of impotence interferes with his attempt to take a third wife. A close-up of a drummer’s hands opens the film with celebratory performances inaugurating Senegalese independence. Even as the theatrics of ridding the Chamber of Commerce of such foreign intrusions as a morose marble bust of Marie Antoinette are revealed to be empty, merely symbolic gestures, music sustains the kernel of rebellion that carries Xala’s narrative to its rightfully vengeful conclusion.

Dieynaba Niang as La Badiene in Xala. Courtesy Film Forum.

Where El Hadji is a stand-in for the failings of an entire class, his flaccidity signals the African bourgeoisie’s inability to enact the emancipatory potential of decolonization as they remain greedily tethered to the colonial gilded cage. El Hadji finds himself in a clash with a band of beggars—a conflict that casts them as the lumpenproletariat, aligned with Frantz Fanon’s denunciations of class antagonisms following independence. As in Emitaï, revolutionary and transformative potential is located in the collective. Many of the beggars have severe disabilities impeding their mobility, and Sembène’s attention to their gestures of shared survival is at times painfully moving, infusing Xala’s merciless mockery with occasional tenderness. In the film’s first hour, during a sequence primarily concerned with the bustling activity of El Hadji’s secretary, the camera descends on one of the beggars sitting just outside their office-warehouse, plucking the strings of a xalam. The instrument is the bedrock of a tune with Wolof lyrics written by Sembène, composed in collaboration with the griot Samba Diabare Samb. As the film’s central musical motif, the song articulates a rebellious demand for justice and bolsters the narrative’s crescendo.

Ousmane Camara as Fara Diogomay the Elder Ceddo in Ceddo. Courtesy Film Forum.

Both the satirical grotesqueries and obsession with talismanic objects in Xala challenge the overemphasis on Sembène as a social realist. Emitaï evinces an even cleaner break with realism when one of the slain Diola appears resurrected during an encounter with the spiritual realm, a moment formally accented by a spectral wash of red over the image. Such apparent discrepancies in Sembène’s atheistic leanings are crucial to discerning the place of religion in his filmmaking, particularly in Ceddo. A spellbinding demonstration of his approach to history as a field open to revision and reassembly, it dramatizes a power struggle as the ebbing Franco-Christian presence and introduction of Islam both loom over an animist ceddo (resistant people) community. The film was banned for eight years, owing to its defiance of the Senegalese government’s insistence that the title term be spelled “Cedo,” and it was considered controversial for its perceived condemnation of Islam. In this rich historical epic, realism is troubled at the sonic level through the anachronistic presence of Manu Dibango’s jazzy soundtrack and African American spirituals, which accompany a scene of French colonial captivity to forge a link to transatlantic slavery. Just as Xala’s maraboutage—a supernatural element; in that instance, a curse—is never dismissed as a false belief, Sembène’s aesthetic divergences from realism in both Emitaï and Ceddo suggest an acceptance of multiple faiths. Consistent with the overarching political architecture of his films, the indictment of Islam in Ceddo does not target the religion as such but more precisely its use as an instrument of domination.

Ismaila Diagne as the Ceddo kidnapper and Tabata Ndiaye as Princess Dior Yacine in Ceddo. Courtesy Film Forum.

Far from seeking to alienate Senegal’s predominantly Muslim population, Sembène championed the recognition and preservation of a plural cultural inheritance. As signaled by his heterodox musical choices and application of oral storytelling techniques, Sembène foregrounded indigenous beliefs and collective memory as the foundations for an emancipatory Pan-Africanist vision. Devoted to being intelligible to an expansive African public, his films were shaped by adapting vernacular forms while sidestepping clinical oppositions between “tradition” and “modernity.” His didactic mission was one of political education, taking on the responsibilities of consciousness raising, which saw cinema as a transformative mirror that could demystify people’s material reality so they might alter it. For Sembène, cinema was night school for the masses and being an artist was a call to arms.

Yasmina Price is a writer, film programmer, and PhD candidate at Yale University. She is devoted to black cinema, anti-colonial visual culture, and experimentation.