Ben Ratliff

Ben Ratliff

Always atypical: a seven-disc box set of work by the

musician and composer.

Julius Hemphill: The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony,

by Julius Hemphill, New World Records

• • •

The elusive conscience of the jazz tradition, its totally appealing layer of resistance to schematic rendering, is something like its protector and saboteur, and always both at the same time. Jazz performs poorly in the marketplace to the same degree that it persists: not as a canon or an academy or a look, but as a flexible and renewable idea.

Which is great, and then there’s the problem of Julius Hemphill, whose totally appealing body of work has barely made it through to new listeners for twenty-five years. Much of it is “unavailable,” as they say, but none of it has benefited from the power of aura, story, inspo, and whatever process that has begun to elevate Alice Coltrane or Nina Simone or Milford Graves. Within that problem is a possibility. Perhaps the reason Hemphill—born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1938, died in New York City in 1995—has evaded the dragnets of cool, blanking out a generation’s worth of reception to his work, is the same reason why his work will persist in spite of them.

A new seven-disc box set of Hemphill recordings released by New World, The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony, has been culled from Hemphill’s archives at the Downtown Collection of New York University’s Fales Library. None of the music has been released before, but some of it is as significant as what was released. It’s enormous. It’s available. It’s inspiring. It takes the first big whack at the problem.

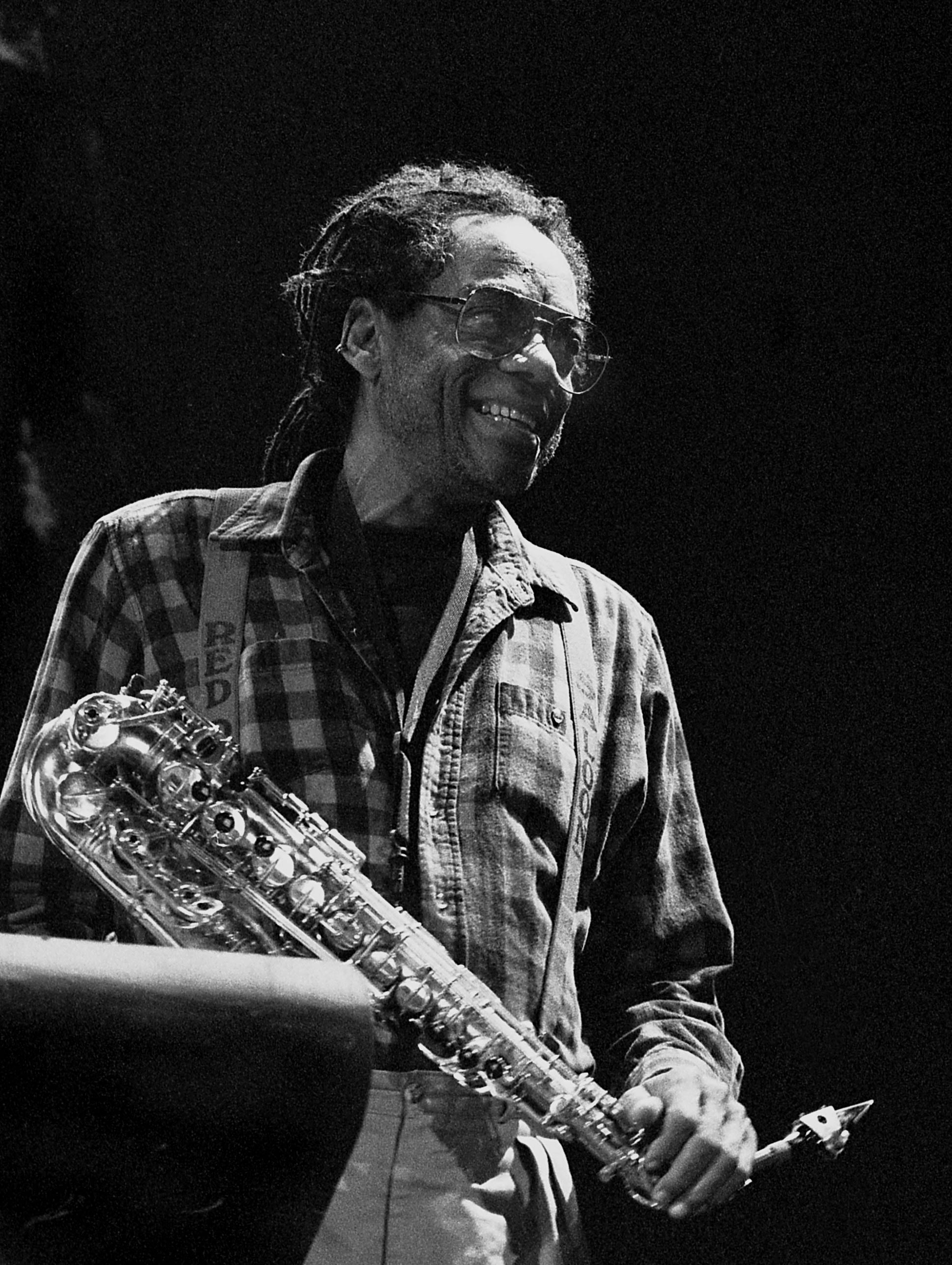

Julius Hemphill rehearsing at the Apollo Theater, New York City, 1990. Photo: Michael Wilderman / jazzvisionsphotos.com.

Hemphill wasn’t larger-than-life, a tragic figure, or even, perhaps, much of a leader, in the managerial sense. He seemed a kind of flamboyant introvert. He avoided standard paths, worked at great pace with skepticism and discipline, and left a lean trail. His music was multiform and so smart that it could be hard to get your hands around. It incorporated his interests in Black history, literature, religion, and ritual; in Dogon astronomy and sculpture; in circuses and minstrelsy and bebop and Marvin Gaye. After he got to New York, in 1973, you can’t track his movements very well by looking for his name in listings and advertisements, because he rarely led a working band. His music might not be revolutionary or funky or spiritual in the ways most recognizable to us now, and much of it was released minimally or not recorded at all. To be really altered by him was to watch him closely, and that could be hard to do unless you sought him out, or sought out someone with proximity to him.

Most of the Crusade music was recorded in small theaters and performance spaces and studios during the 1970s and ’80s. Its best stretches come from, say, the Manhattan Healing Arts Center, in a Tribeca loft; or a campus café at the University of Pennsylvania called the New Foxhole: almost forgotten places. Through sheer length, the box set expands Hemphill’s presence in the major streaming services by about forty percent. But it’s more important that the set comes from the efforts of those close to him, including his partner, the classical pianist Ursula Oppens; and his collaborator and friend, the saxophonist Marty Ehrlich, the set’s dogged producer and writer of annotations about Hemphill’s music for this set as well as the complete archive. The endeavor really tries to understand him; it meets him where he was.

Hemphill’s music distinguishes itself in several ways. One was that he was a great saxophone soloist fair and square. He recused himself from playing standards and could go far outside the chords of his own songs—to that extent he was a “free jazz” musician—but didn’t default to wild gestural overkill. He was a great blues and ballad player; he’d listened hard to Charlie Parker’s tone and rhythm and could make his steadied upper-register sound grow yawing or talky for specific effect. You can hear that all through Crusade, particularly in certain places: for instance, in “Soweto 1976,” a two-man project with the dramatist and actor Malinké Elliott connected to scenes from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man; and the gig at the Healing Arts Center, with the cellist Abdul Wadud and the drummer Michael Carvin, as they charge through an idiomatic tour among jazz eras called “K.C. Line.”

Julius Hemphill performing in Washington DC, 1983. Photo: Michael Wilderman / jazzvisionsphotos.com.

Another distinction—this is the big one—was that Hemphill was a masterly composer. Way, way up there. Somehow, this wasn’t properly acknowledged during his life. He wrote a lot for multiple woodwinds, often four or six saxophones alone. His unusual harmonies around emotive themes were handsome, tart, earthy, unclichéd and almost unplaceable. The best-known of his work like this was in the 1970s and ’80s with the World Saxophone Quartet. You could call his saxophone-quartet pieces like “Steppin’,” “Slide,” “Revue,” and “Bordertown” a response to Duke Ellington, but without the rhythm section; you could also call the WSQ’s achievement, as the critic Martin Williams did in his book The Jazz Tradition, an innovation equal to what Haydn did when he developed the string quartet from the European orchestra. And yet the box set does not include anything by the WSQ, tacitly arguing that his corpus of compositions—somewhere around 235 pieces—speaks for itself even if you subtract its points of greatest exposure.

He was also a collaborator and experimenter in form and format. After he finished army service in Missouri and moved to St. Louis, in the late 1960s, he helped form the Black Artists Group. It was an arts and social-justice organization, supporting rent-strikers and summertime school programs, putting on performances however possible, and multidisciplinary down to the ground. Music wasn’t separated from any other art. So remained Hemphill’s ethos. He never waited for a precedent or an invitation toward the typical; everything he did was atypical. He might use costumes and alternate names. (“Roi Boyé” was one of them, a sort of spirit-persona who made appearances through his work.) He created extended pieces with poets and dancers and experimental theater directors. He made records for tiny labels, sometimes his own, in which he duetted with himself alone or with one other person. This is another aspect of his collaborating: his one-to-one improvised communication with a few musicians, particularly cellist Wadud, had a sensitivity verging on clairaudience.

Julius Hemphill with Marty Ehrlich, Carl Grubbs, and Kenny Berger in rear, Apollo Theater, New York City, 1990. Photo: Michael Wilderman / jazzvisionsphotos.com.

Finally, after all this talk about jazz, it may be right to think about the utter uselessness of that word to contain Hemphill. There is the evidence, on Crusade, of “Parchment,” the first piece he wrote for solo piano, through-composed and seven minutes long, dedicated to and played by Oppens, who is not an improviser. It makes you think: What couldn’t he do? But even a more representative piece of Hemphill’s music, like “Syntax,” from the second disc of this set—a full hour of duets, date and location unknown, with Wadud—expands both the jazz and classical traditions, through its rigor and its performance practice. Like many critics, I taught myself long ago to be skeptical around the idea of “originality”: it’s mostly a construct, and not a useful criterion of value. But being confronted by the real thing can be eerie.

Both pieces—“Parchment” and “Syntax”—are examples of music that writes its own ticket. Such music can’t be protected or sabotaged, because no method exists to do either of those actions to it. We oughtn’t think that Hemphill’s work didn’t have a chance back then, and that now it does; it always has had the same amount of chance. The difference is that now you can point to more of the work, and that it comes attached to—and boxed within—its roots and reasons.

Ben Ratliff is the author of four books, including Every Song Ever.