Ben Ratliff

Ben Ratliff

Pink Floyd, meet Jane Jacobs: in a new book, Damon Krukowski embraces the noise.

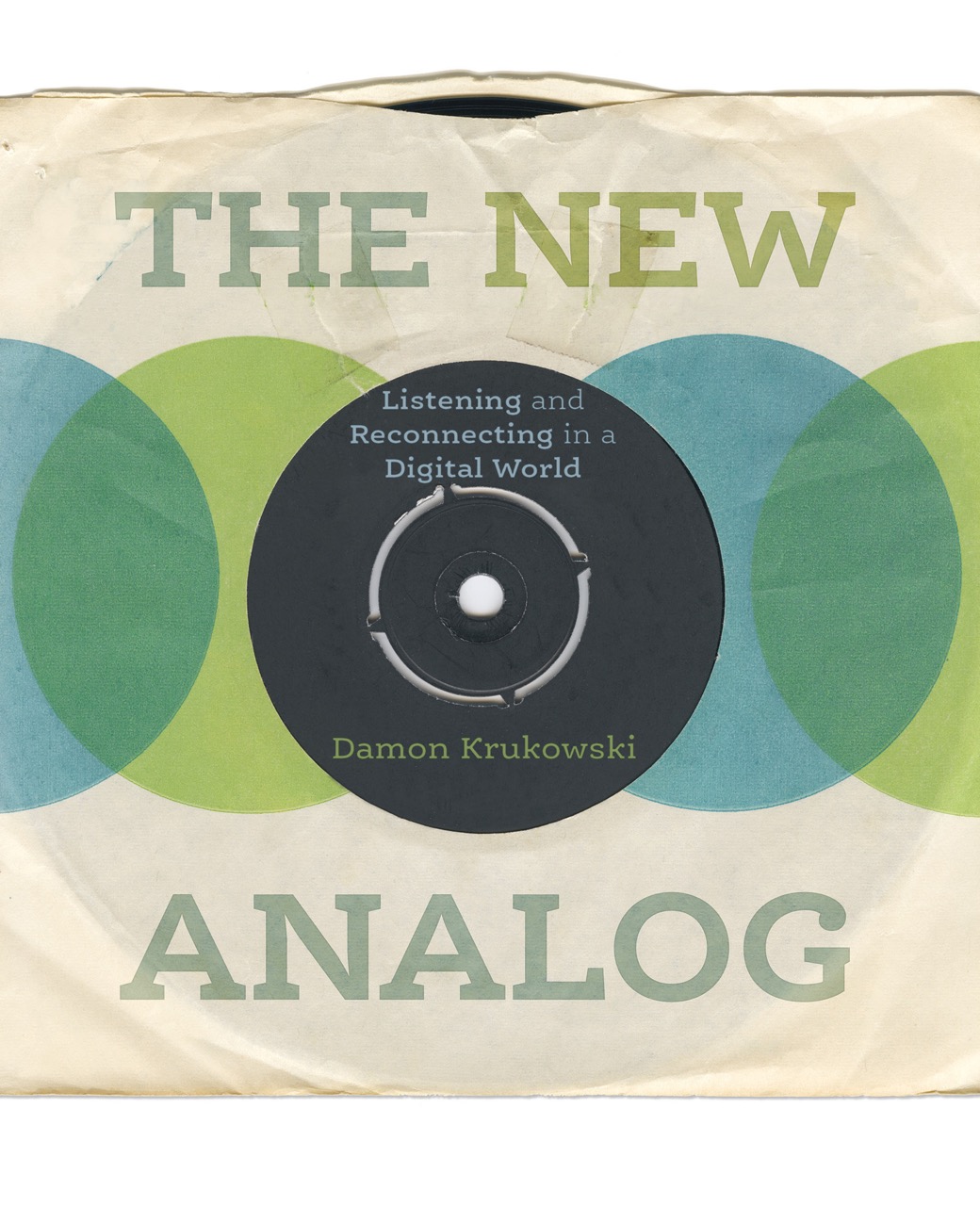

The New Analog: Listening and Reconnecting in a Digital World, by Damon Krukowski, New Press, 224 pages, $24.95

• • •

What “analog” in the realm of music represents, to many people who are not audio technicians and some who are, is an abstract preference for taking the long way to do something that can otherwise done more efficiently.

This preference is easy to mock. I am thinking of Alex Gregory’s New Yorker cartoon from May 25, 2015. A pair of middle-aged men stand before an analog home-audio setup, which includes one of those expensive audiophile turntables with a really thick revolving platter—about the dimensions of a flourless cake—as well as a tube power amp. One guy, bald on top, has put his hands in his pockets, to signify that he is a man of measured enthusiasms. The other guy folds his arms; he has a shaved head, to signify that he is radical at heart. Both have their mouths open slightly. It doesn’t matter who’s talking, but the caption reads: “The two things that really drew me to vinyl were the expense and the inconvenience.”

Analog sound has never really been my cause. This is partly because of my reluctance to become one of the men in the cartoon, and also because I see that my field, music criticism, has become broader and faster since the rise of cheap digital recording, streaming services like Spotify, and the mp3. My causes run more along the lines of listening broadly and deeply now that almost everyone can, and of considering the process of history that led to whatever music it is you’re listening to. This is, I have now learned, also an analog issue. Damon Krukowski’s The New Analog quantifies analog as a set of values that quickly go beyond music, toward ideas of perception, communication, self-preservation, and history. He is trying, as he says, “to define aspects of the analog that persist—that must persist—that we need persist—in the digital era.” The book grows only as abstract as the subject is worth; it is also brief, logical, and elegantly written.

Analog, he reminds us early on, “refers to a continuous stream of information, whereas digital is discontinuous.” It doesn’t matter whether we are talking about music or anything else. “Any division of information into discrete steps,” he continues, “is a digital process: from counting on our fingers, to calculating using an abacus, to (at least in some musicians’ view) plotting notes on a staff of music. Yet our senses remain resolutely analog.” This is a useful idea, and it prepares you for a series of interrelated chapters: on location within the “space” of sound, with particular attention to Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon; on microphones; on the perception of depth and loudness in sound; on the understanding of time through sound. He stresses music as a form of communication, and he doesn’t mean that metaphorically, which is why he spends fifteen pages on copper-wire telephone lines and the carbon mics inside pre-1980s rotary phones.

Krukowski is a rock musician. He was in the late-eighties band Galaxie 500, with his wife Naomi Yang, and they have continued to make records together ever since as Damon and Naomi. But he is not arguing for analog out of a vested interest in selling you higher-priced vinyl (or, perhaps, only in a small way). He’s not reducing analog vs. digital to soulfulness vs. music-industry greed. Rather than ask either-or questions turning on money and time—digital, y/n?—he is doing the work of a critic in suggesting that such a question is an incomplete one, partly because it is a digital question.

Another way of talking about analog is to talk about signal and noise. “A microphone amplifies not only what we say through it—the signal—but everything around that signal, which sound engineers call noise,” he writes. Many of us reject the idea of noise, considering it a form of interference; we would prefer signal, and the purely useful information it may be thought to contain. Digital means the transformation of sound into data, which results in the possibility of eliminating noise. Analog, on the other hand, can only be signal plus noise.

One of Krukowski’s big ideas connecting these chapters is that we need some of that noise, because noise encodes music in a particular moment. Within that noise is a larger story, beyond the notes. “Noise” encompasses—to recite some of his examples—the tiny speed fluctuations made by the tape machines used by Led Zeppelin; the sound of the air conditioners behind the final chord of the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life”; Frank Sinatra’s technique of shifting his distance from the studio microphone to increase dynamics. Krukowski has a nice way of putting this: “noise is as communicative as signal.”

He speaks sound technician and psycho-acoustician and electrician, but keeps his arguments within the realm of the humanities. Among his inspirations, he writes, is Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and her arguments about how the theories of postwar city planners seemed to ignore the specific ways that people use those cities. But The New Analog could also be put next to Susanne Langer’s Philosophy in a New Key, Jaron Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget, Amiri Baraka’s “Jazz and the White Critic,” and any number of other texts that try to bring the professionalized notions of “data” and “information” (and, by extension, “signal”) into balance with the sometimes undervalued notion of lived experience.

And so while you’re reading The New Analog it’s a book about Frank Sinatra, telephones, and Spotify, but when you put it down it might be about Apple, click-bait journalism, and the White House, to name three manifestations of the twenty-first century’s cult of disruption. Disruption involves the division of information. It is discontinuous and therefore digital. History is continuous, and analog.

Ben Ratliff is the author of four books, including Every Song Ever.