Sukhdev Sandhu

Sukhdev Sandhu

“Right, noise!” A collection of essays probes the Fall.

Excavate! The Wonderful and Frightening World of the Fall, edited by Tessa Norton and Bob Stanley, Faber & Faber, 360 pages, $30

• • •

“Hello, Milwaukee!” “It’s great to be here!” Bands walking out on stage often perform euphoria. Not the Fall. Appearing at the rain-soaked Deeply Vale free festival in summer 1978, the Greater Manchester group’s front man, Mark E. Smith, snarled, “Good afternoon! When I was on the witch trials of the twentieth century, they said, ‘You are an aesthetic anesthetic. Your repetition will never be.’ Right, noise!” Small wonder that, a year later, journalist Graham Lock began an interview feature with them, “Talking to the Fall is like wading through a river at night. Nothing is clear, and there’s nothing to get hold of.”

Excavate! The Wonderful and Frightening World of the Fall, assembled by Tessa Norton and Bob Stanley, is an essay collection by visual artists, novelists, and musicians that knows not to hold the Fall too tight or treat them as a jigsaw puzzle to be completed. An impossible task. Formed in 1976, lead singer Smith invented more personae—Fiery Jack, Roman Totale, Carry Bag Man, Slang King, Hip Priest—than anyone since David Bowie. His lyrics were barbed, allusive. (“Spectre vs Rector” begins: “M. R. James vivat vivat / Yog Sothoth Ray Milland / Sludge hai choi, choi choi son.”) He ejected band members with the indifference of the Conservative government closing coal mines in the 1980s. Music, far less “independent” music, was only one of his creative chisels; Hey! Luciani, his play about Pope John Paul I, featured Leigh Bowery; he collaborated with choreographer Michael Clark on the ballet I Am Curious, Orange; cowrote a horror film, The Otherwise (its screenplay soon to be published by Strange Attractor Press).

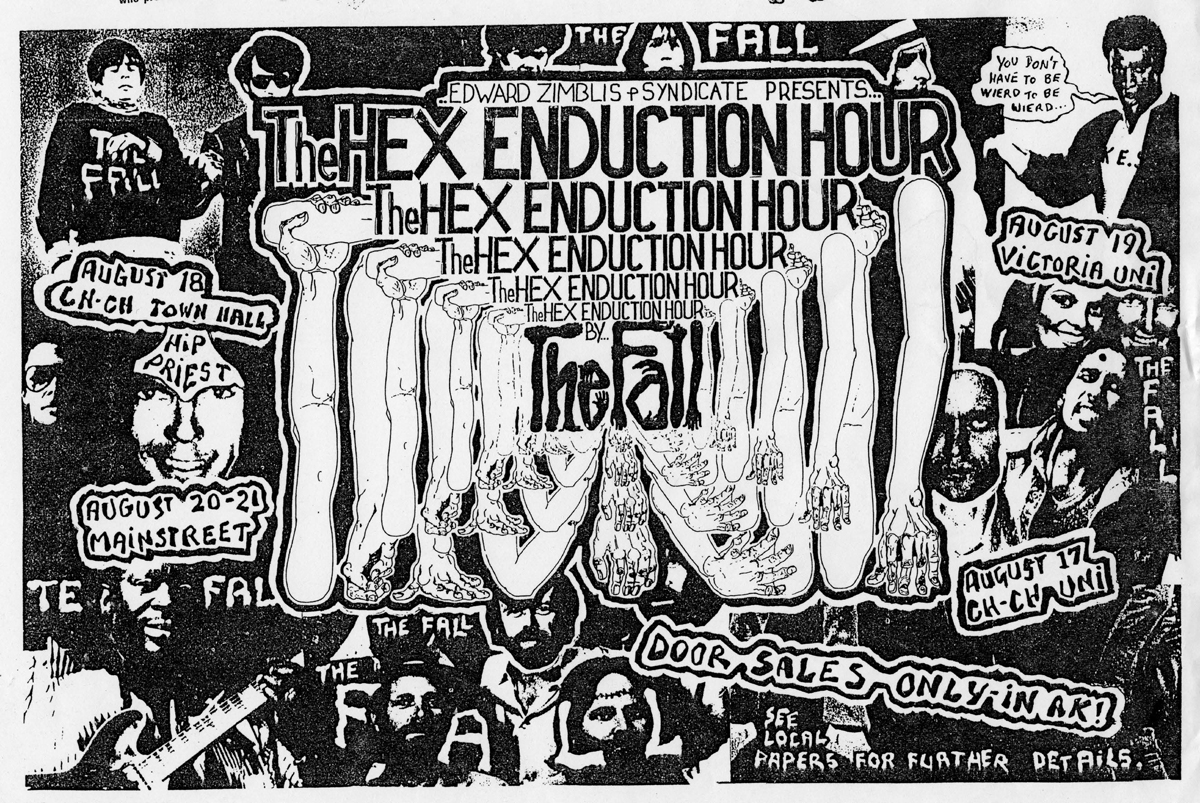

Flyer reproduced in Excavate! The Wonderful and Frightening World of the Fall, edited by Tessa Norton and Bob Stanley. Courtesy Faber & Faber.

The Fall’s border crossings, their provocations and productiveness, their edge and endlessness: Norton, in her essay, argues that they’re less a band than a counter syllabus. Smith himself left school at sixteen and was sniffy about the educated classes. (He was known to sing “Oh Student!” to the tune of “Hey Fascist!”) Still, Norton likens the Fall to para-academic projects such as Black Mountain College and Alexander Trocchi’s proposal for a Spontaneous University. Smith, with his love of Stockhausen, H. P. Lovecraft, and (bizarrely) the sitcom Keeping Up Appearances, becomes a reverse coder, an apostle of avant pulp, a “paperback shaman.” His fractured, fugitive curriculum was initially “transmitted through cheap FM radios to teenagers in darkened bedrooms under duvet covers.”

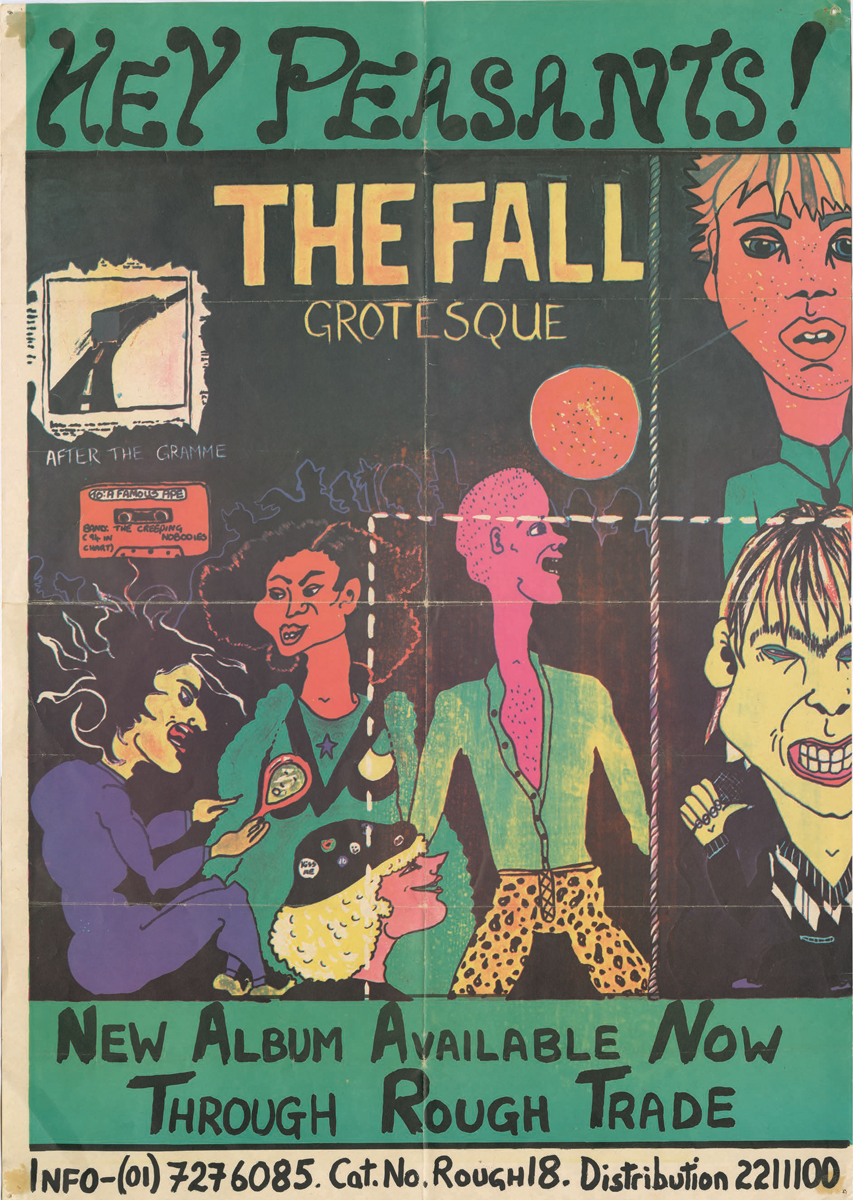

Flyer reproduced in Excavate! The Wonderful and Frightening World of the Fall, edited by Tessa Norton and Bob Stanley. Courtesy Faber & Faber.

A school of Mark E. Smith probably wouldn’t be the most inclusive or nurturing of environments. “The Fall is like a Nazi organization,” he once declared. It’s said that he fired a sound engineer for eating a salad. Band members were forbidden to play solos or do anything that hinted at improvisation. “The consumer is not getting everything on a plate” was his explanation for banishing lyrics from album sleeves. One Excavate! contributor, architecture writer Owen Hatherley, views such behavior as a refracted legacy of the scientific management techniques developed by Frederick Taylor at the start of the twentieth century. Others might see it as Apprentice-style CEO-ism.

Smith was a Blitz kid. Not the New Romantic club of that name beloved by peruked androgynes and thrift-store Beau Brummels at the turn of the 1980s, but the older Blitz—rubble and residues of World War Two, Brits versus Huns, spy thrillers and espionage stories. Of his snot-and-slur accent, claimed his first, American-born wife Brix, “It was Mancunian, but it sounded more like German to me.” His earliest jobs were in a meat factory and as a poorly paid clerk at the Manchester Docks. During the recessional late 1970s, even those jobs were disappearing. Mark Fisher’s essay talks about how the rockabilly in “Fiery Jack” has been “slowed by meat pies and gravy, its dreams of escape fatally poisoned by pints of bitter and cups of greasy-spoon tea.” Smith, who once described the Fall as “Northern white crap that talks back,” often came across as a screwface version of kestrel-loving Billy Casper in Ken Loach’s Kes.

This is an England that has turned Brexit blue in recent years. Smith originally wanted the band to be called Master Race and the Death’s Heads. An early song was “Race Hatred.” They played Rock Against Racism shows and heckled the leader of the National Front. Not a few of their songs offered dry, spindly dub topped-and-tangled with Smith’s riddle-me-this, riddle-me-that / I overstand you vocals of early ’70s reggae MCs. But—or should that be and?—he was also pro–Falklands War, never shy of making anti-French jibes, and, in the 1982 song “The Classical,” used a racial slur that has led to debate over whether he himself was a racist. Nothing rubbed Smith the wrong way so much as liberalism’s insidious embrace. He cultivated a heroic indifference to Southerners, critics, and a fanbase that, by the 2000s, seemed mostly to be made up of avuncular blokes in their forties. He preferred to see the Fall as heretical outsiders, as northern English Maroons.

Smith may have been into art rock bands such as Henry Cow, but, as Dan Fox astutely points out, he also identified with American rock and roll—in “R&R as primal scream.” He loved Link Wray, Gene Vincent, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley. Among his band’s best-known songs were covers of garage, Northern Soul, and surf tunes—albeit, Fox adds, “surf music made by a band who had no clue what sun, sand and sea looked like.” For a few years in the mid-1980, the influence of guitarist Brix could be heard in the band’s freshly buffed sound. She’s one of the women—others include early manager Kay Carroll and keyboardist Una Baines—whose contributions are rightly highlighted in Excavate!

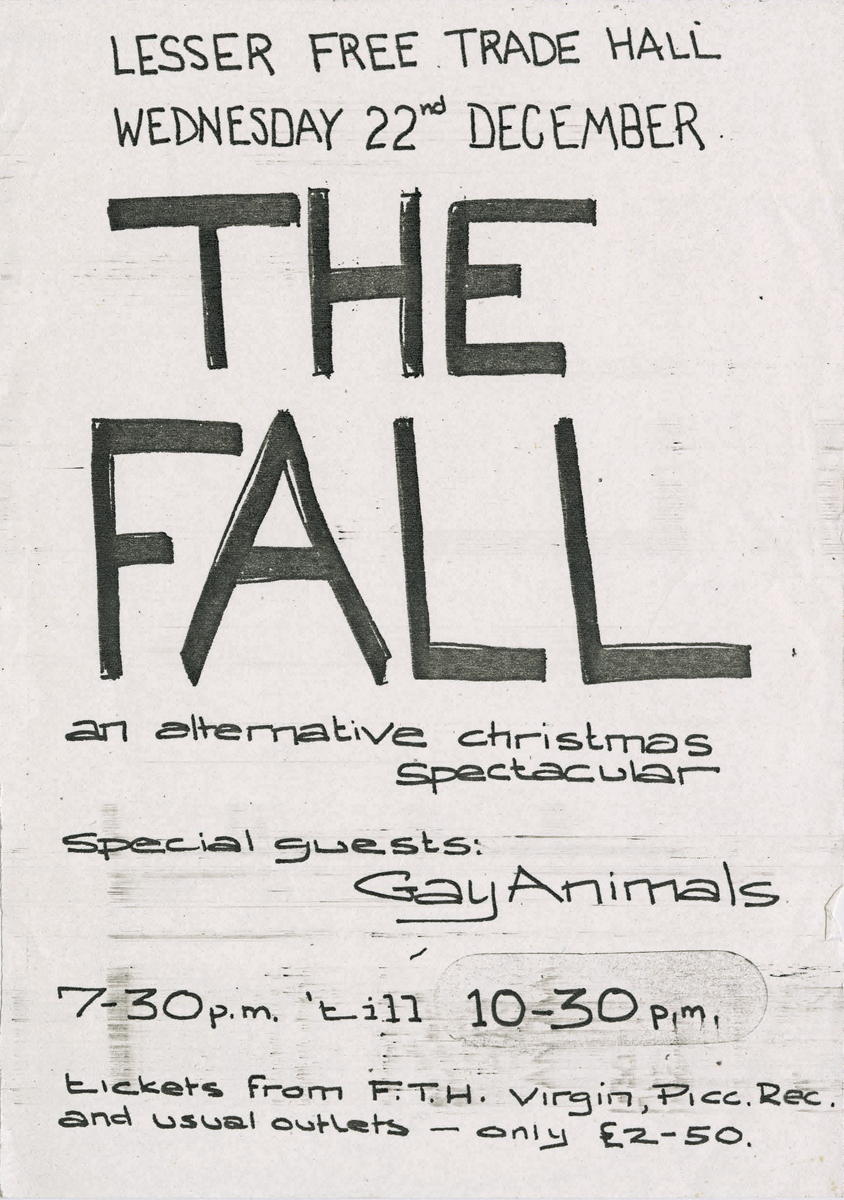

Flyer reproduced in Excavate! The Wonderful and Frightening World of the Fall, edited by Tessa Norton and Bob Stanley. Courtesy Faber & Faber.

Norton and Stanley make a point of emphasizing the Fall’s visual identity. Their early record sleeves—outsider-art graphics, erratic exclamation marks, ransom-note handwriting, Burroughs-style cut-ups—were as compellingly hieroglyphic as the music. They gave tantalizing hints that, right from the outset, the Fall could never be defined by the label “postpunk.” The band manifested in—but did not belong to—the 1970s. They were revenants and wraiths, hosts to ancient viruses, channelers of those seventeenth-century nonconformists contributor Ian Penman itemizes as “firebrands, malicious schismatics . . . mechanic preachers, downright ranters.”

Smith passed on in 2018. His voice and spirit, band member and ex-wife Elena Poulou has written elsewhere, will endure “like a drizzle, a gentle megaphone, like a notification on your phone—every day and night.” He was a difficult sod. A magnificent clot of insubordination.

Sukhdev Sandhu directs the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University. A former Critic of the Year at the British Press Awards, he writes for the Guardian, makes radio documentaries for the BBC, and runs the Texte and Töne publishing imprint.