Yasmine Seale

Yasmine Seale

Amid a life of both brutal and mundane cruelties, Turkish writer Tezer Özlü’s memoiristic novel brims with a vital force of desire.

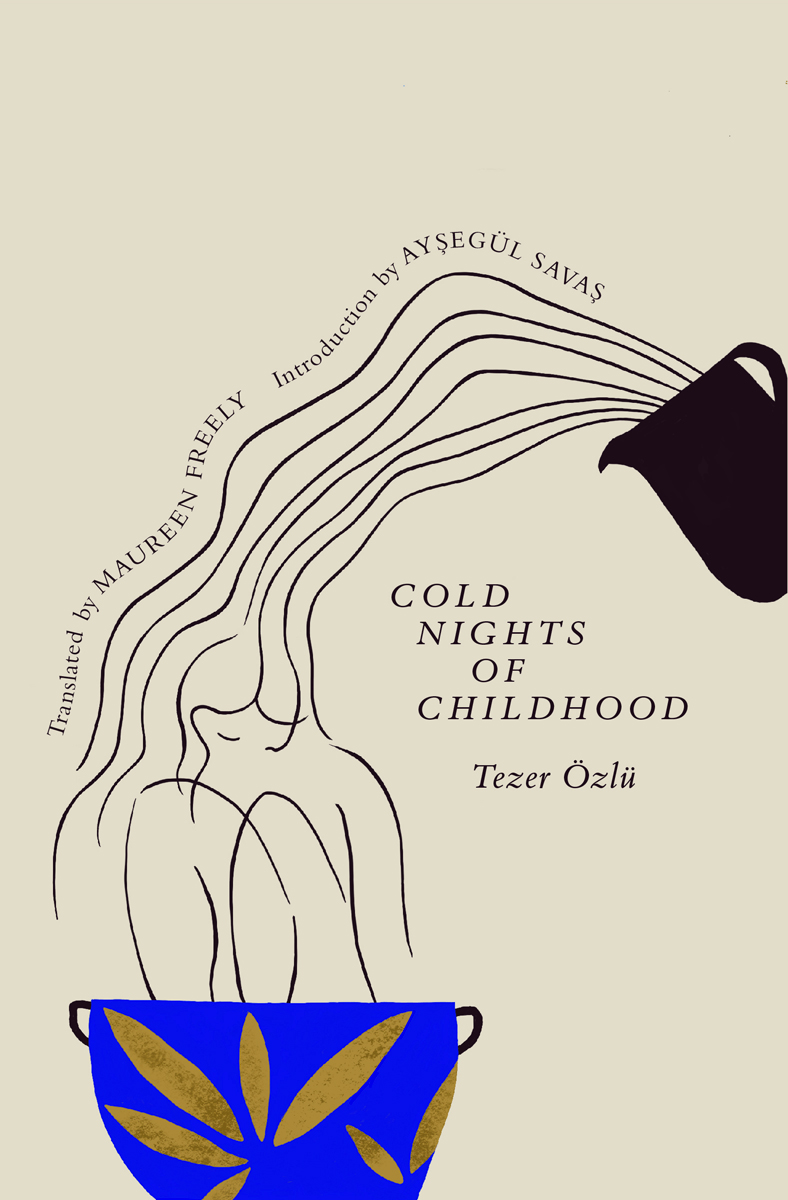

Cold Nights of Childhood, by Tezer Özlü, translated by Maureen Freely, Transit Books, 111 pages, $16.95

• • •

Born in 1943 to patriotic Turkish schoolteachers, Tezer Özlü was one of three children who left home at the first opportunity and became writers. Many intellectuals of her generation turned to socialism, rebelling against the state their parents had served, and ran aground in the waves of repression that followed the military coups—three in as many decades—that punctuated their young lives. Özlü, though not unfriendly to her peers’ commitments, stood aslant: her rebellions took a different form, and so did her incarcerations. She came of age in and out of psychiatric clinics, a torment she survived and out of which she forged an odd, fragmented style that was to leave its print on her successors. “Her small oeuvre,” writes Ayşegül Savaş, “has always had a devout following . . . for its madness, its honest sexuality, its lack of national fervor and its individuality.” Cold Nights of Childhood is Özlü’s short, autobiographical first novel, published in 1980 and now translated into English with typical éclat by Maureen Freely.

“A woman’s nature,” wrote Edith Wharton in a story, “is like a great house full of rooms.” There is the hall, the drawing room, the sitting room where relatives come and go, and beyond other rooms whose doors are perhaps never opened is a secret room where “the soul sits alone.” Özlü, unlike Wharton, grew up in modest quarters; her subject is what happens to the soul when horizons are cramped, when all the rooms are crowded into one. Descriptions of the novel’s confined spaces read like maps of closely observed prisons, of which the first is childhood. In Istanbul, where the family moves from the provinces, the young unnamed narrator (let’s call her Tezer) shares a bed with her sister, receiving her first orgasms and wondering about God as their grandmother sleeps on a mattress beside them. Like Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon, another reimagined memoir of acerbic candor, the book opens with an austere, domineering father blasting orders to his children. “Don’t slobber!” thunders Ginzburg’s patriarch; “No pussyfooting in the army!” barks Özlü’s. Nine pages in, still a girl, Tezer attempts suicide in protest at “these armchairs and carpets . . . these rules”—the strictures of petit bourgeois life.

A violent hunger for freedom, when it fails to kill her, sees her through. If home is miserable, school—one of Istanbul’s prestigious foreign institutions, the legacy of nineteenth-century missionaries—is worse: an Austrian convent run by nuns, “each . . . mad in her own way,” who may or may not have a shaven cross on the top of their skulls, beneath their veils. The pupils intone German prayers; in unison they chant “America is our brother!” Tezer and a friend escape into Zola and Dostoevsky, whose world of pain and poverty they recognize, and later into the taverns and patisseries of the old European quarter, which form the heart of the artistic scene. A ghostly poet in a houndstooth coat is Tezer’s guide through this bohemia, where she is admitted to a circle of writers and begins an ambivalent tango with desire. “It takes many years of effort to get used to men, and to love their sexual organs.”

Chafing even at the bounds of time and place, the text moves skittishly between cities, lurching like memory. Its longest, most experimental section starts in Berlin, brimming with “unquenchable life.” Tezer wants to write; a fragile equilibrium beckons. But at the turn of a line, in one of Özlü’s signature gear changes, she is back in Turkey, kept against her will in a hospital that smells of “abnegation,” where she suffers abuse at the very hands of those who hold “the keys to the doors that will return us to reason.” It is the site of her most cruel education. “I shall learn to lie down smiling for electric shock treatment.” The spring of 1971—which saw widespread arrests under martial law, including of Özlü’s brother—finds her in a stupor, only dimly registering the turmoil around her. Across the thin partition that separates the healthy from the sick, or simply the excessive, she considers her friends: “They eat in a measured way . . . They believe in their work. They talk of revolution but take care not to lose their footing. They don’t step into marriage as thoughtlessly as if they’re stepping into a car . . .”

Husbands and lovers bleed into each other, promising deliverance from the sadism of doctors but ending up as their accomplices. There is an abortion and a wedding on the same page; the more harrowing is not the one you might think. “I’m drunk. I have no idea where I am . . . I listen to the registrar’s words as if she’s telling me a joke.” Tezer’s teenage attempt on her own life, by contrast, is recounted with almost bridal ardor: “For days now, I’ve been making the necessary preparations to ensure that my dead body looks beautiful.” For all the grim material, Özlü is bracing, almost cheering company. Acquaintanceship with death charges the writing with a queer vitality. Take this jagged portrait of her grandmother: “It’s been seventy years since she last slept with a man. She loves life. Nothing interests her more than her own funeral.” The characters are not “rounded,” because neither are people; we exist to each other as a handful of shards. The usual lubricants of narrative, coherence among them, are needled as so many sentimental fictions.

Cold Nights of Childhood might be understood as a revenge on the convulsive therapy that robbed its author of much of her twenties, and from whose jolts she invented a new syntax. Like electroshock, the novel has no duration, “no midpoint.” Each sentence inhabits its own moment, pitched into the next by sheer wattage of verbal energy. Freely, in a moving afterword, writes of Özlü’s “way of fashioning a paragraph, which cut right through the many straitjackets, real and metaphorical, that were forced on her.” By the time she composed the book, between two Augusts in the late 1970s, she seems to have found escape velocity, if not tranquility; a steadier voice, speaking from some more hopeful future, breaks through the text at even intervals between parentheses. The last few pages are an impassioned hymn to life’s many-splendored gifts, its windows of transcendence: purple dawns of the Aegean, red poppies on the Taurus mountains, the smell of frying mussels. A new passion begins, absorbing and redeeming all past loves. “My long years of suffering have not destroyed me. They’ve only guided my heart.” Özlü’s second novel, written in German, takes place in trains and in hotels, in movement: a travelogue through Europe in the footsteps of her favorite writers. It was her last. She rewrote it in Turkish, as Journey to the Edge of Life, shortly before her death from cancer at the age of forty-three.

Yasmine Seale lives in Paris, where she is a fellow at the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination.