Helen Shaw

Helen Shaw

The body in the bog: Jez Butterworth sets his big new play

during the Troubles.

Paddy Considine as Quinn Carney (center, standing) and the company of The Ferryman. Photo: © 2018 Joan Marcus.

The Ferryman, by Jez Butterworth, the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, 242 West Forty-Fifth Street, New York City, through February 17, 2019

• • •

After its breathtaking success in London, Jez Butterworth’s Olivier Award–winning new drama, The Ferryman, has sailed to Broadway with a strong wind behind it. Over yonder it was a near-unanimous critical hit; audiences lapped up its mix of Northern Irish family revelry, chilling menace (it’s set at the height of the Troubles), and eerie fantasy. And the production itself is intent on entertaining us: There are real fluffy bunnies! A real cuddly baby! A real indignant goose! It’s a crowd-pleaser, a potboiler, a soap opera with a razor in its pocket. It also pulls apart at its own seams.

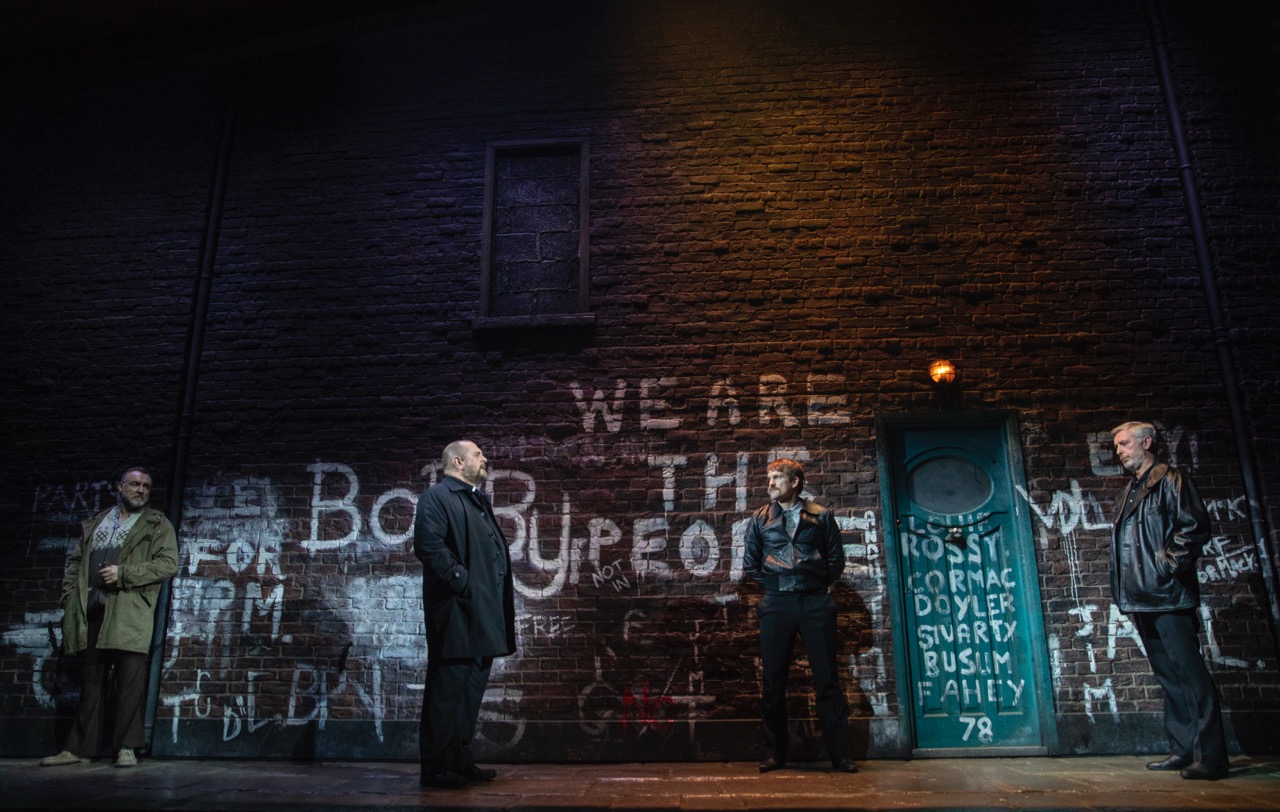

Glenn Speers as Lawrence Malone, Charles Dale as Father Horrigan, Dean Ashton as Frank Magennis, and Stuart Graham as Muldoon in The Ferryman. Photo: © 2018 Joan Marcus.

On a gray day in 1981, a body comes out of a bog—after nearly ten years, Seamus Carney has been found. In a swift prologue, the frightening IRA leader Muldoon (Stuart Graham) gives this news to priest Father Horrigan (the wonderful Charles Dale), who’s then sent off to tell the family, particularly Seamus’s brother Quinn. There’s a throb of rock ’n’ roll, and bang! We suddenly find ourselves in the Carney clan’s home, a gigantic, cozy farmhouse out among the fields of County Armagh. The mood here is warm and light. Paterfamilias Quinn Carney (film veteran Paddy Considine) and Caitlin Carney (Laura Donnelly) are at the tail end of a night spent laughing, dancing blindfolded, and setting the table lamp on fire, seemingly through sheer physical chemistry. As day breaks, the pair steers their enormous family around the kitchen: Caitlin shaves jocular old Uncle Pat (Mark Lambert), makes breakfast for the swarm of little girls, fends off vinegary Aunt Pat (Dearbhla Molloy), fusses at her teenage son Oisin (Rob Malone), organizes the baby (a rotating cast of gurgling sweeties), and shouts instructions to the oldest boys (Niall Wright and Fra Fee). In the merry confusion, Quinn marshals the lads for the harvest—because the crop is coming in.

Niall Wright as JJ Carney, Matilda Lawler as Honor Carney, Justin Edwards as Tom Kettle, Mark Lambert as Uncle Patrick Carney, Fra Fee as Michael Carney, and Willow McCarthy as Mercy Carney in The Ferryman. Photo: © 2018 Joan Marcus.

Harvest time means all sorts troop in and out. Cousins Diarmaid and Shane from Derry (Conor MacNeill and Tom Glynn-Carney) will help, and the local gentle giant, “curly-wurly fingers cuckoo” Englishman Tom Kettle (Justin Edwards), shall put his shoulder to the wheel. There is a copious amount of establishing how happy the family is and the way that many hands make light the work; it’s a giddy whirl. Even the near-comatose Aunt Maggie Far Away (Fionnula Flanagan) wakes up so that she can sing about fairy changelings—while an invisible neon sign marked FOREBODING flashes overhead.

Because all isn’t what it seems. Quinn’s not just a farmer, he’s an ex-soldier in the IRA. And Caitlin isn’t Quinn’s wife. That’s Mary (the cut-glass Genevieve O’Reilly), who drifts downstairs eventually, a hypochondriac ill at ease in her own home. Most of the kids are Mary’s; Caitlin is actually Seamus’s widow, though all these years she’s not been sure he’s dead. The IRA has been taunting her with lies that he’s been seen abroad, keeping, as Quinn says, “the wound open.” (The play’s title image refers to Charon, who refuses to take the unburied dead across the Styx.) Once Father Horrigan delivers his news, other secrets start crawling out too: Caitlin and Quinn’s unsaid longing for each other, certainly, but also deaths going back generations and the promise of violence to come.

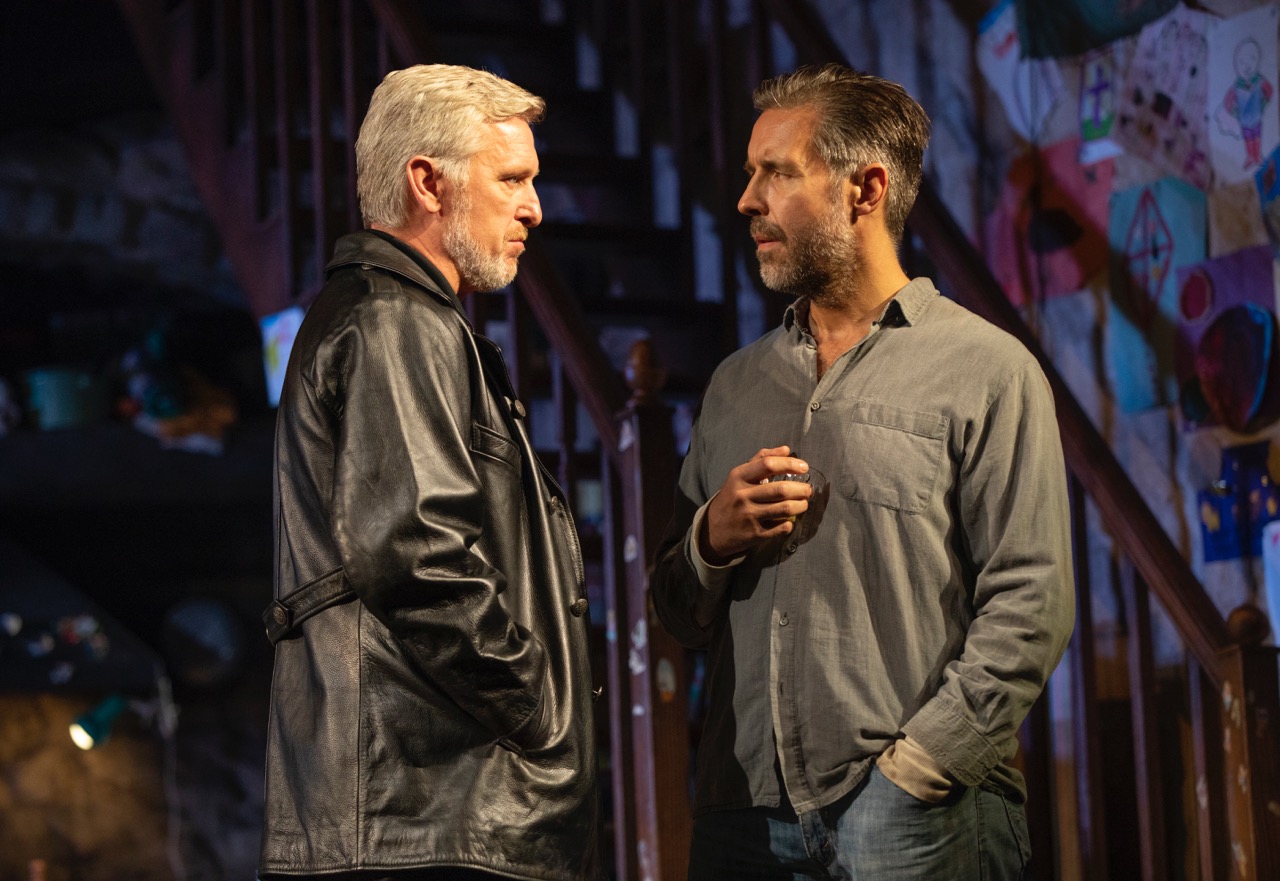

Stuart Graham as Muldoon and Paddy Considine as Quinn Carney in The Ferryman. Photo: © 2018 Joan Marcus.

Butterworth, an Englishman, tills the harvest metaphor as many poets writing about Northern Ireland have before him. Seamus Heaney has a poem about the barley that comes sprouting from republican graves, the literal seeds of the 1798 Wexford Rebellion (the rebels carried grain in their pockets) becoming the figurative germ of the Easter Rising. Indeed, Oisin and Shane are two of Heaney’s new green shoots, and when Muldoon and his men finally walk into the joyful, bright cottage, you see the boys’ faces go hard with worship. In one tremendous whiskey-drenched scene, four of the passionate teenagers sing the praises of the hunger strikers in Belfast—Michael Devine starves to death as the family feasts—and we’re reminded that, even now in 2018, these are unquiet spirits.

After I saw The Ferryman, I went home, thought about it, and then bought a ticket and went again. I’ve only done that with two other shows—and one of those was Butterworth’s Jerusalem. Butterworth has the gift for density, which takes time and consideration to parse. In his play The River, it was density as magma-thick language; in Jerusalem, it was an ultra-compact central character—Butterworth poured all England’s awfulness and beauty into one man, and the play bent toward him. In The Ferryman, though, there’s a forced quality to Butterworth’s hallmark overfullness. As he intends, the play is chockablock with excitement and children underfoot, but sadly it’s also brimming with clichés (wee drams, singing, step dancing, the good folk, rainbows) and obvious borrowings from other stories (Of Mice and Men and Long Day’s Journey into Night, not to mention a barrel of Yeats). The Butterworth aesthetic is still dizzying and heady, but this time, because of the broad stereotypes, you can see the edges on the collage. I returned to Jerusalem because I loved it; I went back to The Ferryman because I couldn’t understand why a play wringing everyone else like dishrags was leaving me cold.

The company of The Ferryman. Photo: © 2018 Joan Marcus.

And honestly, sitting with it for another three-plus hours wasn’t hardship. That first-act reveal of Caitlin and Quinn’s true relationship is masterful, and boisterousness makes for easy watching. But the bits that clang, like Aunt Maggie’s I-saw-banshees-in-the-woodshed shtick, kept clanging. The funny thing is that Butterworth often identifies what’s powerful, and then undercuts it. For instance, this noisy play is actually about silence and absence—from Seamus’s ten-year hole-in-the-world to Mary’s marital retreat, from the void between Tom Kettle’s ears to the nothingness in Muldoon’s heart. Ironically, Butterworth then overstates his theme. Tom Kettle (unbelievably) recites all of Raleigh’s “The Silent Lover,” which talks about the greatness of unspoken love, and then, in case we didn’t get it, the girls yell at Caitlin about how Aunt Maggie never talked to her childhood love. “Can you imagine, Aunt Kate? She never told him!” Oh, you’ll yearn for the wrenching silences again—especially since the third-act romantic confessions are terribly cheesy. (“I love you more than the future,” etc.)

Laura Donnelly as Caitlin Carney. Photo: © 2018 Joan Marcus.

Since the third act doesn’t quite work, Butterworth cranks it up to eleven. Director Sam Mendes and Butterworth accentuate each other’s over-egging qualities here: Mendes has composer Nick Powell layer in unearthly wails (first time they’re chilling, tenth time, they’re funny), and the IRA thugs, particularly the eel-slick Muldoon, are hammier than Easter lunch. So thank god they’ve got Laura Donnelly. She’s forthright, raw, vulnerable, vivid. The characters around her are often showboaters and “types”; she’s as real as a knife in a drawer. It’s a shame, then, that the play pivots away from Caitlin and toward the baffled-seeming Quinn. As in Jerusalem, Butterworth asks one character to contain all the centrifugal forces of his country, but this time the playwright puts that whirlwind into the wrong person. At the end of the play, as things turn to shit, we wonder what Caitlin will do, but instead she has her choices, her child, and finally her weapon literally taken out of her hand. In its final moments, the play is turned over to Quinn, and Considine (here in his stage debut) can’t bear up under the part’s staggering requirements. Donnelly as Caitlin could handle it though. Forget Charon—she could actually row this boat to shore.

Helen Shaw writes about theater and performance in publications such as Time Out New York, Art in America, Artforum, and diversalarums.com.