Christine Smallwood

Christine Smallwood

In Ian Penman’s new book, a chatty and insightful examination of the life and legacy of Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

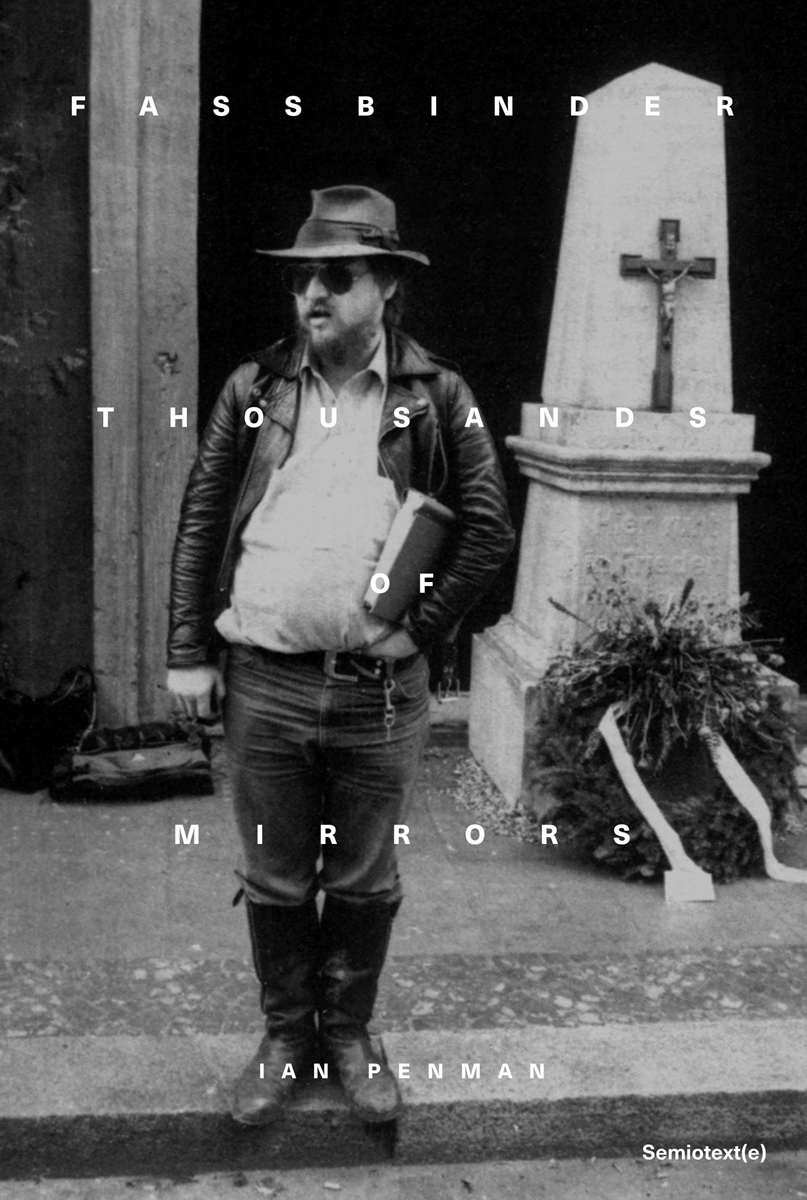

Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors, by Ian Penman,

Semiotext(e), 195 pages, $16.95

• • •

In 1978, Rainer Werner Fassbinder told an interviewer for the German television series Life Stories that he was writing a novel. “It’s a story about someone who one day can no longer move and faces the choice of either finding out . . . why he can’t move or no longer breathing,” he said. Cigarette smoke is wafting over his face. His shirt unbuttoned halfway to his belly. “And he decides to find out why he can’t move anymore. And in the end he can move again.”

He never finished the book (he seems scarcely to have begun it). If it is strange to imagine Fassbinder, who never stopped moving, writing a story about immobility, it’s all too easy to see how he would imagine a lack of movement leading to asphyxiation. This is a person for whom the concept of rest was theoretical at best. From the icy classics of the late 1960s (Love Is Colder than Death, Katzelmacher), through the Sirkian masterpieces of the early 1970s (The Merchant of Four Seasons, Ali: Fear Eats the Soul), all the way to the gorgeous melodramas of The BRD Trilogy and the hypnotically stagey Querelle, Fassbinder worked at a manic, heroic, grueling pace, churning out as many as three or four films a year. He wrote, he directed, he acted, he produced, he worked the camera, etc. A “monster of productivity,” writes Ian Penman in the sneakily brilliant Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors. Also: “a true monster of selfishness.” And don’t forget: a “mythic ogre.” Well, this is the man who Jonathan Rosenbaum said “improbably evoked both John Belushi and Andy Warhol.” Penman calls him a real-life Rumpelstiltskin, behaving badly all the way into the abyss. “Choreographed tantrums and micro-fascism: RWF is at one and the same time beadiest critic and most egregious example,” he writes. But he “met all his deadlines, every one.”

Penman, a music journalist and critic who, as a young alt-culture omnivore in 1970s London, fell hard for Fassbinder, has put off writing about the man, the work, the drugs, the whole emotional racket, for decades: “For the longest time, not writing this book was itself a way of not coming to terms with various things.” At last he decided to “proceed in the spirit of” and pound it out in a few months’ time. He got going, in the early days of pandemic isolation, by rewatching the films. “It turns out however that being stuck inside an airless room for what might well be an eternity is not the best formula for watching films about . . . people stuck inside cheerless rooms tearing lumps out of each other for what might well be an eternity.”

Thousands of Mirrors is wise and chatty, keenly observed and casual. Its form (an essay in numbered fragments) allows Penman to loiter on at least two main avenues and various side streets. On the main drag, he attempts to understand RWF—who was he then, what is he now, and why isn’t he more widely worshipped? What are these cramped, controlled, semi-hysterical films doing, and how do they do it? What is this mixture of sadomasochistic relationships (RWF: “my subject is the exploitability of feelings”) and aesthetic pleasure, color, light? On these lines Penman is sharp and unsentimental. He notes early on that he does not wish to “sum up” or “watch every last film and give it a mark out of ten.” He’s not that interested in writing about individual films at all. About Fear Eats the Soul he says only (but isn’t this everything?) that it is “a series of precise framings of people on thresholds.” He lingers over Despair, not because it is good, but because, like a camera to a catastrophe, Penman is “utterly magnetized” by even the biggest misses. Ultimately the book isn’t about Fassbinder himself; it’s about—here we arrive on the second avenue—Penman’s attempt to understand his own love and ambivalence for Fassbinder’s work. Fassbinder didn’t have the chance to grow up—he died at age thirty-seven, in 1982—but Penman did. Time changes everything; there are cynicisms that, half a century on, he can no longer tolerate. “Perhaps he does finally emerge as a villain, in some respects . . . Perhaps I really should have taken someone else as a role model: someone in it for the long haul, not a tyrannical child.”

Penman puts his nomadic childhood on various RAF bases next to the insecurity of RWF’s childhood; his own drug use is referenced obliquely. Riffs on Benjamin, Derrida, Barthes, Mann, and Genet come together as intellectual autobiography. He goes down all the alleyways: musings on postwar Germany; on RWF as punk or post-punk; on modernism, shock, sleeping, and dreaming; on Sirk, Nabokov, doubles, television, and a persuasive theory of the cinema as “entertainment bunker.” Thousands of Mirrors has style to burn. It has no angst of big questions and puts itself under no burden to answer them. “What kind of being is being on film? What kind of being is being an image?” reads one fragment, in its entirety.

“Did he fundamentally lack imagination?” Penman asks. “I don’t say this to be needlessly poisonous . . . His inability to imagine another world may be at the heart of everything he did and all he achieved.”

It’s true—the stories are unhappy, on- and off-screen. Fassbinder’s was a fallen world of cruelties, humiliations, suffering. That was the point: history had made it so. But, Penman cautions: “We must never lose sight of visual pleasure, never forget just how beautiful his films could be.” Underscore that. Has anyone ever made a dead body in a station, having its pockets picked, look so good? Has any neon light ever blinked as forlornly, as pinkly, as the one in Franz Biberkopf’s apartment? Has anything ever been lovelier, or sadder, than Ingrid Caven lying naked in that tacky bedroom while Hans Hirschmüller mopes beside her?

Fassbinder, famously, preferred to shoot scenes only once. He made art as life makes us—at one go, one chance for each take. This technique, more than anything else, explains the energy in his work. Even in the most frozen and unnatural of his shots, there is some intensity, a concentrated desire to make something happen. In artificial hothouses, real passions struggle to be born. Sometimes those are even real hearts tossed into the grinder. He liked to zoom in on faces. And they are so interesting, the ones he chose: so ordinary, so ethereal, so angular, so pudgy, so vicious, so needy, so twisted—chief among them, his own. His bodies are poseable and expressive. And the women! They don’t quite hold Penman’s interest, but they are at the center of RWF’s art and legacy. Their legs, their tan lines, their tears. They express more, the more they are constrained.

As Penman rightly observes, to take pleasure in Fassbinder is to take comfort in the “familiar” and “familial” aspects of his work. His films are an album or a group portrait. “Maybe this novel is an attempt to free myself from the necessity of working with other people,” Fassbinder said on Life Stories. “That doesn’t mean I really want to free myself from it.” No one needed other people more than he did. And yet: “Fassbinder’s films are among the most acute depictions of loneliness in modern cinema,” Penman writes. Or, as Fassbinder wrote of Sirk, “People can’t live alone but they can’t live together either.”

Christine Smallwood is the author of the novel The Life of the Mind.