Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

In the musician’s new four-song EP, shimmering waves of sorrow, heartache, and passion.

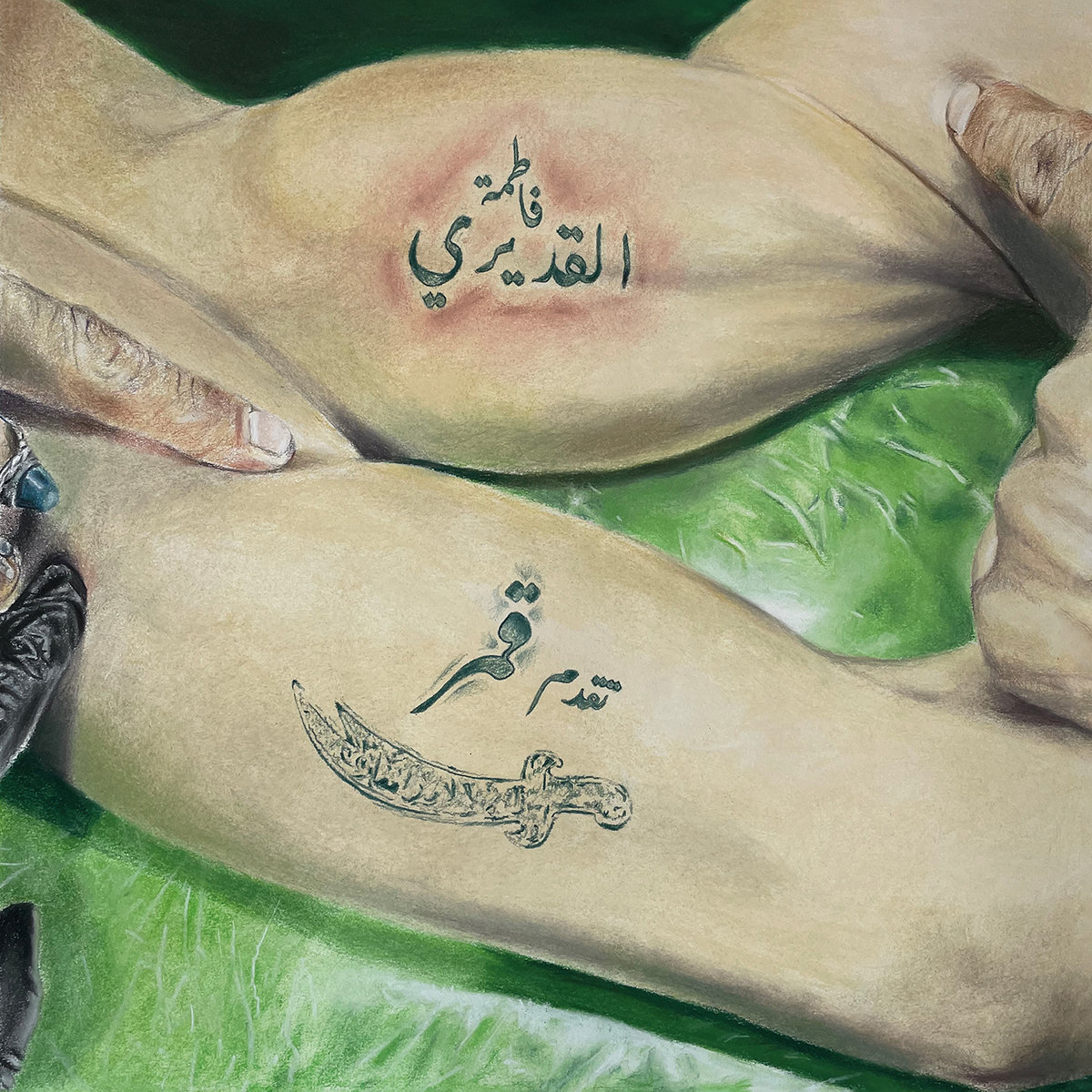

Gumar, by Fatima Al Qadiri, Hyperdub

• • •

If the conceptual setting for Fatima Al Qadiri’s 2021 album Medieval Femme was a mystical garden, the space of her new EP, Gumar, is an ocean—an ocean sublime and sepulchral, lulling and laving with loss, glinting with shards of the moon controlling its tides, the listener both wracked and subdued in its waves. The first single released off this concise, four-song, ten-inch record was “Mojik (Your Waves),” which the musician describes as “an ode to drowning.” Its theme is composed of six notes of synthetic strings that irregularly ascend and descend across unsettling and inquisitive minor tones, keeping time like jagged waves themselves, a theme soon flooded by shimmering sound that swells and ebbs as an elegant masculine voice, hoarse at its edges, transcendentally repeats, over and over for three-plus minutes, a single refrain, in Arabic, which translates to “Your waves, your waves have killed me o sea.”

Gumar (both Arabic for “moon,” a word, in classical poetry, often standing in for the loved one, and the name of that mournful singer, a friend of Al Qadiri’s from Kuwait) comes in a straight line from her soundtrack for Mati Diop’s Atlantics. The 2019 film is a tragic supernatural romance, a romance of possession, in which men who died at sea, trying to make the treacherous passage from Dakar to Spain, return to land as spirits who enter the bodies of the living. Before Atlantics, Al Qadiri was best known for her deft synthesis and reworkings of modes of dance music, like her outrageous 2017 EP of queer club tracks, Shaneera; and for concept albums singed with violence, like the 2012 EP Desert Strike, an ode to a video game she played with her sister growing up in Kuwait after the Gulf War, or the 2016 work drawing from protests against police brutality, Brute. Al Qadiri has said in interviews that Diop pushed her toward a place of quiet and stillness that she found fascinating, which took her on the path to the elysian Medieval Femme, though the otherworldly green of this Elysium is shaded with colors of longing—the record is based on the melancholy themes of medieval poems authored by Arab women.

In Gumar, melancholy has become condensed and impenetrable, like a cruelly glittering diamond so entrancingly beautiful you would give your life before you would relinquish it. Al Qadiri says the EP is based on traditional Arabic songs of lamentation, a tradition with which she grew up and in which singer Gumar was trained. To sing a lament can be a formal way to mourn. For Freud, famously, the difference between mourning and melancholy is that through mourning, you are able to get over your loss, whereas in melancholy, you pathologically refuse to—you crystallize your loss inside yourself so that you don’t have to feel so alone, as if you were filling up your emptiness with a representation of itself. In this way, the lamentations of Gumar are less acts of mourning than cascades of melancholy—singing the fathomless hurt of unrequited love, the songs refuse to let the loved one go, they give shape to the unbridgeable abyss between the lover and the loved one, name the absence with a repetition that will make it last forever.

Left: Gumar. Photo: Abdullah Al-Mutairi. Right: Fatima Al Qadiri. Photo: Corinne Schiavone.

What’s particular about longing, as opposed to wanting or desire, is that its object moves perpetually out of reach—the temporality of longing is infinitude. The first track on the EP is the eponymous “Gumar (Moon),” which manages to contain that infinitude in a slender one-and-a-half minutes. The singer’s voice overwhelms, accompanied only by a skeleton of a gently broken melody on a quiet keyboard. In the song’s sound-image, he is not in front of that melody, but rather seems to come down toward the listener from above, his passion having untethered him from the gravity that keeps those unpossessed by love upright and steady on the ground. “O Moon, O Moon, where? O Moon, O Moon, where are you?” Gumar extends that vocative particle, “yah” in Arabic, to a painful climax, with a melismatic rendering of the open, unrounded vowel—the kind of sound that keeps your mouth stretched wide and defenseless, the very picture of yearning. But then the subject of its invocation, “gumaru,” suddenly drops in tone and volume, is uttered quickly, as if the singer has expended all his energy on calling for it, and has no energy left to name the thing itself.

The second track, “Fidetik (I Lay Down My Life For You),” is suddenly dangerous-sounding, menacing synth horns droning a lugubrious tempo to underscore Gumar’s thick emotion as he intones the declaration of the title, as if in a trance, percussion abruptly slamming into the sound-image like a portent, until all the music fades away and only his plaintive voice is left. I would die for you—it feels like a warning as much as an offering. The last track, “Meriem,” “a simple heartbreak song,” is musically the most detailed and elaborated, shaded in with contrasting registers of sound that overlap and recede, a holographic keyboard motif in the center, as Gumar sings the name of the title in a dozen different ways: attenuated and beseeching, low and commanding, a desperate exclamation. There is an eroticism in the enunciation of a proper name. In D. J. Enright’s version of Proust’s Swann’s Way, when Gilberte calls Marcel by his first name, he feels “held for a moment in her mouth, myself, naked.” In Al Qadiri’s song, Gumar may desire to cradle Meriem on his tongue like that—but she is not there to hear him, cannot be drawn between his lips.

In pearl-diving cultures of the Arabian Gulf, such as pre-oil Kuwait, there is a song of lament based on the form of the mawwal, an improvisatory, elegiac song of keenly pitched emotion. In these sea-songs, the singers may drone to imitate the sound of the depths of the sea that has laid claim to the bodies of the lost divers; these supernatural-sounding choruses were often associated with djinn. Gumar is like a descendent of these laments, without the paranormal chorus. Al Qadiri’s earlier records had been marked by such an uncanny choir, one created by cutting up samples of human voices and programming them to synthesizer keys, but the choral sample is notably absent on Gumar. We are confronted with just the achingly human, rawly flesh-and-blood voice alone, singing above and through the delicate nets of Al Qadiri’s spare synthetic sounds. Infinitude and death, impossible longing and mad possession, despair and despairing hope are all embodied in it. Listening to that voice, my heart broke into its ocean.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.