Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Coconauts! Revolutionary ectoplasm! A show tracks the intersection of art and science fiction.

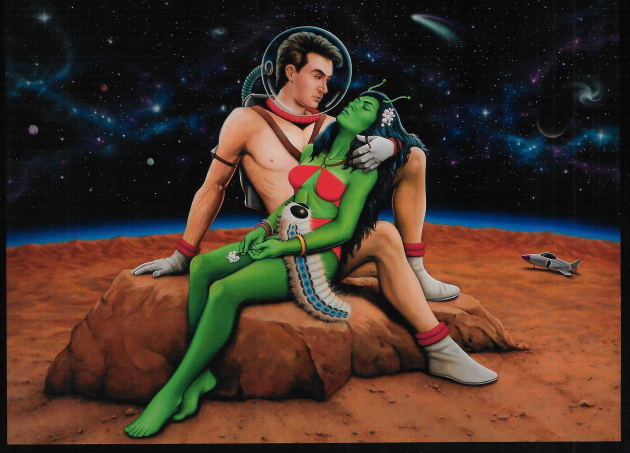

Laura Molina, Amor Alien, 2004. Oil paint, fluorescent enamel, metallic powder, 35 × 47 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas, Queens Museum, New York City Building, Flushing Meadows Corona Park, Queens, through August 18, 2019

• • •

“EL HOMBRE NO HA DE TERMINAR EN LA TIERRA,” Gyula Kosice ardently declared in 1944. Man is not to end on earth! The Argentine artist continued to dream of liberation from the tyranny of soil and gravity until his regretfully earthbound death in 2016. Kosice’s program for an air-born exodus from tellurian existence is now on view in Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas at the Queens Museum, where it keeps company with over sixty other artworks that use that pulpy genre as fuel for jet packing to planes of experience estranged from accepted reality.

Mundos Alternos was first organized in 2017 at the University of California, Riverside, as part of the massive Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA exhibition, opening the same month that Hurricane Maria decimated Puerto Rico and shortly after the Trump administration quietly began enacting its “zero tolerance” policy of kidnapping migrant children at the US-Mexico border. These are among the dystopian present-day realities in the Americas that presumably anyone would desire to be estranged from—but the exhibition’s curators (Robb Hernández, Tyler Stallings, and Joanna Szupinska-Myers) are not offering mere escapism. Their goal is precisely the opposite: to bring together art that macerates US-imperialist, capitalist constraints on viewers’ imaginations until their minds achieve the elasticity that will be required to “decolonize the future.” Their ambition, in other words, is a revolution in consciousness.

It’s a high-stakes, lives-on-the-line proposition; as Chicano sci-fi author Ernest Hogan has noted, under the current global order, not everyone has a future left to imagine. But despite this dire context, and the weighty demands being made of the artworks, the show is often funny: many of the artists share a tendency toward winking satire, absurdity, cuteness, and camp. Early science fiction works in Europe and North America, steeped in colonial fantasies of conquering alterity, might be read as examples of what philosopher Bolívar Echeverría called la blanquitud, or “whiteyness”: a mode determined not only by ethnic features, but by a self-repressive Protestant ethic and “surplusvalue-productivitistic” mentality that serves capitalist expansion. In this exhibition, artists counter that grasping “whiteyness” with decidedly impractical folly.

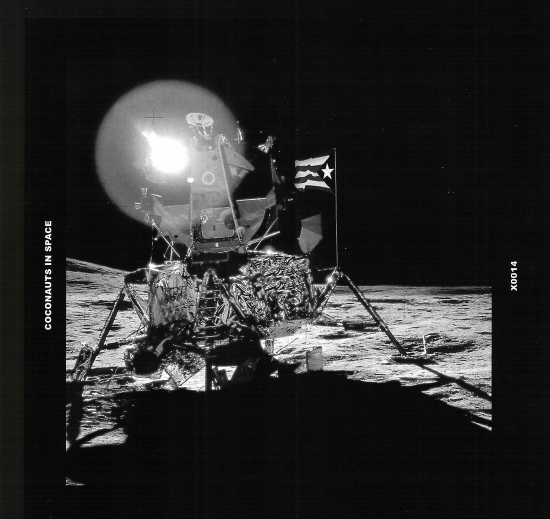

ADÁL, Coconauts in Space, 2016. Twenty prints on metal, 20 × 20 inches each. Image courtesy the artist.

In the first gallery, ADÁL’s Coconauts in Space (1994–2016), a grid of twenty black-and-white photographic prints on metal, presents “evidence” that Puerto Rican “coconauts” were really the first to land on the moon. The series is based on actual NASA photos of the 1969 Apollo landing, digitally doctored to include a Puerto Rican flag and other artifacts from the territory. A lunatic, manically unpunctuated text on the last panel introduces the mysterious Dr. Agápetus Ocula, who was discovered by NASA on the lunar surface six years after the coconaut expedition. The former resident of an unnamed Caribbean island (a stand-in for Puerto Rico, presumably) that disappeared after it was colonized, Ocula and his compatriots had found refuge in the “out-of-focus” dimension of Villa Borrosa (“blurry town”); sadly, due to convoluted circumstances, he ended up being committed to an institution on the moon dedicated to treating “the optically aroused.” Nearby is an interstellar work of a different sort: the genderqueer performer Robert “Cyclona” Legorreta’s Headdress (1989/2017), a proudly elaborate assemblage of humble materials. Glitter-smeared Styrofoam spikes with lightbulb spear tips fan out around a bedazzled miniature altar, in which dangles a golden “third eye” for nonbinary perception; Legorreta wore the fabulous piece in a performance of “cosmic orbiting movements.”

Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas, installation view. Pictured: Robert “Cyclona” Legorreta, Headdress from Transcend, 1989/2017. Photo: 4Columns.

On the other side of the exhibition space is the jubilant Autonomous InterGalactic Space Program. The interior of this vividly chromatic, house-like structure is adorned with small paintings declaring revolution against the “monsters of capitalism,” prodigious crocheted flowers, a modest reading room, and finally, at its heart, a giant corncob-shaped spaceship steered by wooden snails disguised with the iconic black ski masks (pasamontañas) worn by Zapatistas. The ship transports a little living garden crowned with a rainbow archway; woven straw baskets, representing corn kernels, embroidered with bright portraits of anonymous people wearing the pasamontañas; and a stowaway bandit leopard. This striking iconography, springing from Zapatista politics and Mayan cosmic symbology, was devised by members of indigenous communities in Chiapas, Mexico, through a decade-long collaboration with Portuguese artist Rigo 23. On the installation’s long exterior wall, a mural testifies, “Queremos un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos” (we want a world within which many worlds fit)—a joyful alternative to the hegemonic Judeo-Christian monoverse and its destructive hierarchies.

Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas, installation view. Pictured: Rigo 23, Autonomous InterGalactic Space Program, 2009–present (ongoing). Photo: 4Columns.

Other artists counter la blanquitud with a humor inflected by more ominous undertones. For his ten-minute video Alien Toy (La ranfla cósmica) (1997), the Los Angeles–based Rubén Ortiz Torres acquired a white Nissan pickup truck like those used by US Border Patrol agents, complete with that agency’s logo on its doors, deformed to read “Alien Toy.” He hired Salvador “Chava” Munoz, an award-winning builder of the famed lowrider cars made popular by SoCal Chicano communities, to rig the truck with a hydraulics system that would animate the vehicle with such frenzy that it would bust apart in thrilling agitation. The video splices together cheesy found-footage clips of UFO sightings and monster movies with sequences shot in an arid patch of desert. Here, the patrol vehicle whirls and spins and bops in an arrogantly bravura dance until it’s reduced to a hysterical robot, robbed of any purpose except to violently undo itself.

Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas, installation view. Pictured: José Luis Vargas, El retorno de Albizu, 2009. Image courtesy Queens Museum.

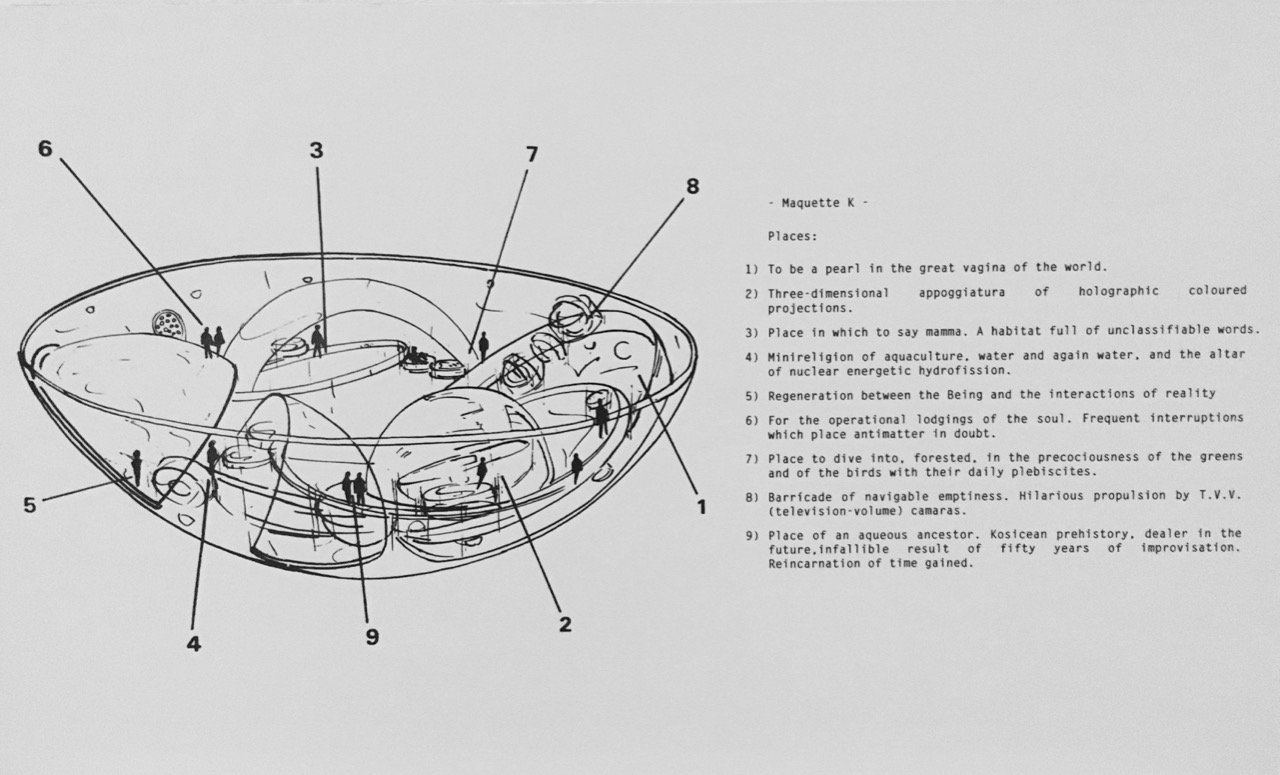

Then there are the more mystical interventions, such as José Luis Vargas’s looping video projection El retorno de Albizu (2015), crafted as part of his larger, collaborative Museo de Historia Sobrenatural project, which revisits Puerto Rico’s colonial past and present through the lens of indigenous spiritual traditions. In the quiet video, three men sit in a circle, immobile, as the air begins to shimmer whitely around them, until a cloud of ectoplasm spills forth: the spirit of early twentieth-century revolutionary Pedro Albizu Campos, who spent nearly three decades in prison for attempting to overthrow US rule of the island. And in the same gallery are Kosice’s diagrams for his decades-long Hydrospatial City project, accompanied by a 2003 animation of his translucent dwellings wafting some 3,500 to 5,000 feet above the earth. Kosice’s proposal for urban renewal required all the nations of the world to divert their military budgets to this new, hydrogen-powered, airborne community, where people would abide in see-through rooms dedicated to such pursuits as recording “in writing—with ink from clouds—the enjoyable radication of all desires,” tobogganing backward down avenues of water, and abstaining “from having a past.”

Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas, installation view. Pictured: Gyula Kosice, Maquette K, 1965–75. Photo: 4Columns.

The current academic and curatorial vogue for subaltern technofuturist imaginaries (Afrofuturism and its conceptual comrades) can sometimes seem driven by an exploitative craving for the spectacle of “exotic” difference. But such “whitey” designs don’t appear in Mundos Alternos, an exhibition based on ambitions that are as exhilarating as they are insane—or perhaps it’s the insanity that is exhilarating, the impossible idea that art could be strange enough to transform our brains, so that we might enter a portal to a brighter elsewhere and leave our ruined past behind.

Ania Szremski is the managing editor at 4Columns.