Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

Remember, remember, the eighteenth of November: in Solvej Balle’s strange and thrilling septology, an antiquarian bookseller contends with the mystery of having to relive the same day repeatedly.

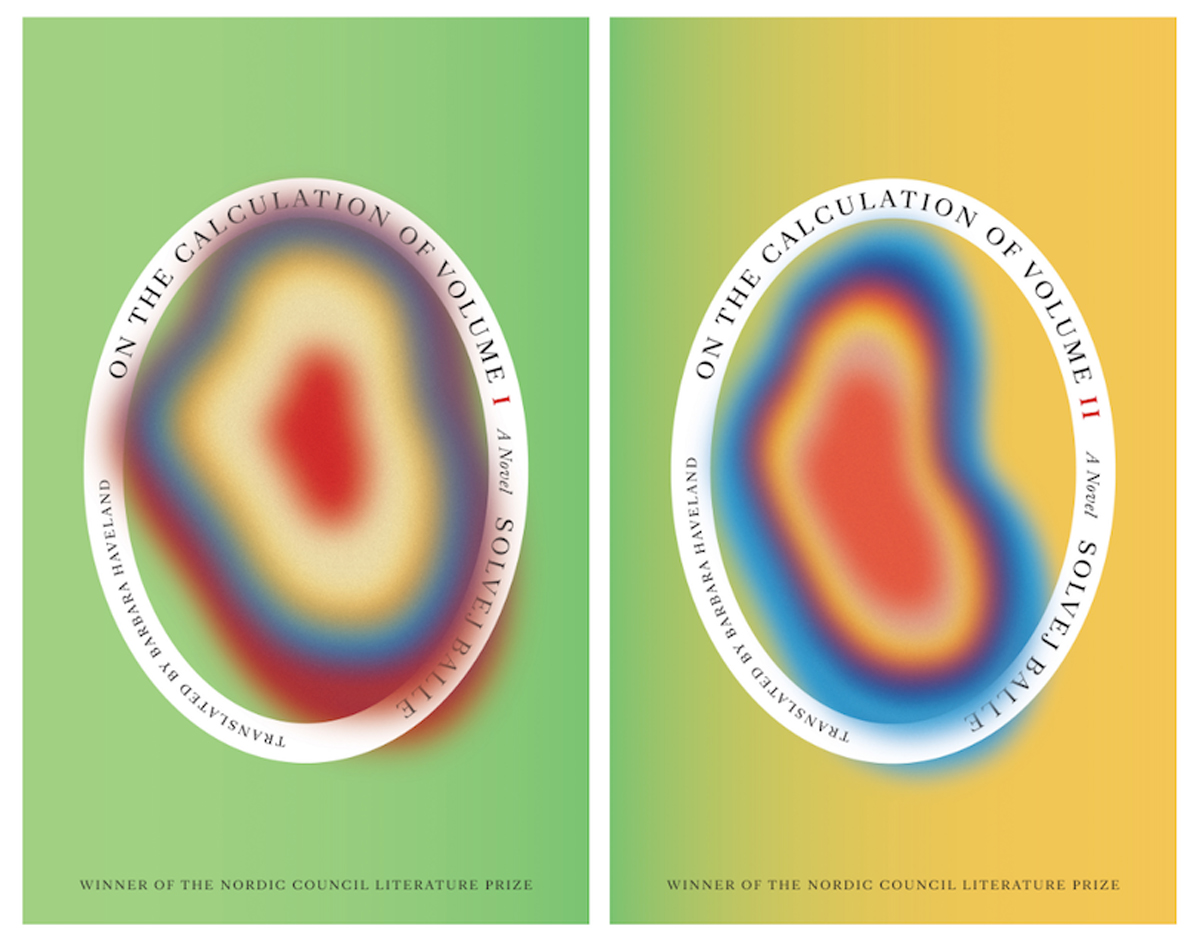

On the Calculation of Volume I & II, by Solvej Balle, translated by Barbara Haveland, New Directions, 161 pages and 185 pages, $15.95 each

• • •

There is a conspiracy theory circulating online claiming that time is now passing faster due to an increase in the Earth’s Schumann resonance (it’s so-called “heartbeat”), and an associated acceleration in its rotation, so that twenty-four hours now feel like sixteen. Time certainly appears supercharged to many of us these days, though it probably has more to do with high-speed informational overload and other subjective factors (like ageing, which slows down our brains, making everything seem to whip by around us). But for Tara Selter, the protagonist of Danish author Solvej Balle’s septology On the Calculation of Volume (the first two books of which are now available in crisp, elegant English translation by Barbara Haveland), the problem is quite different. If time can be understood as a relative measure of change, if time’s perceived flow, its relationship to bounding forces like gravity and entropy, make “reality” legible, then her reality has become unreadable, because it is no longer changing at all—time has stopped, glitched, stuttered, suddenly contracted to a single point. It has ceased acting like a river for Tara—it has become a room, a vessel, a container. For one day, she woke up on the eighteenth of November, and the next day, she woke up on the eighteenth of November again, and this has gone on until she has lived through hundreds of eighteenths of November, years of eighteenths of November, an infinity mirror of identical days, and no one else is aware of this repetition.

The recursive day is a wildly popular premise perhaps most familiar to US audiences from the execrable 1993 film Groundhog Day, but that it here becomes something so strange, so compulsively readable, so thrilling, is testament to Balle’s taut narrative skill and mesmerizing use of language. If time has ceased flowing for Tara, for the reader its flow is exhilarating, propelling us through the slender pages of these two compact volumes, each of which ends on a tantalizing cliff-hanger inciting our desire for more (that the third and fourth installments will not be available in English until November 2025 is, for me, a terrible cruelty!).

Book one begins on the 121st of Tara’s eighteenths of November, which we know because this is the day she has begun keeping notes on loose-leaf paper, kept in a black folder, about what has happened and is continuing to happen to her. She is currently in her two-story stone cottage just outside the fictional town of Clairon-sous-Bois is northern France, a home she shares with her husband, Thomas Selter, and which was inherited from his grandfather. They are antiquarian booksellers who have formed a company together, T. & T. Selter, and Tara’s present story begins on the seventeenth of November, when she went to Paris for an auction, the 7ème Salon Lumières, to acquire more leafy illustrated treasures for their collector clients. She stays at her usual Hôtel du Lison, and the next day buys some rare tomes and has dinner with an antique coin dealer, Philip Maurel, and his assistant-girlfriend, Marie, where they discuss the surprising recent rise in the general popularity of historical artifacts, an interest until then relegated to specialists and arcane collectors. Tara accidentally burns her hand. She returns to her hotel. She goes to sleep. She wakes up. The day starts all over.

Panicked, Tara swiftly returns to the two-story cottage, where Thomas is surprised to see her, because he is still living in the original eighteenth of November. She explains what has happened. He believes her. They discuss what might be at the root of this problem, and how they might solve it. They go to sleep—and then Tara must explain, the next day, all over again, and again each day that follows, until she realizes the temporal distance between herself and her beloved is growing too great, too many eighteenths of November have piled up between them. Time is still passing for her—the burn on her hand heals, her hair grows longer, she discovers small wrinkles—but not for him. To protect both herself and Thomas from this remove, she hides herself away in the house, choreographing her movements around Thomas so that he does not know she is there, so that she no longer sees him, he is reduced to a symphonic score—a creak on the stairs, a splash of urine, the brushing of a hand or sleeve against the wall. (This is a book of minutely described sounds.)

The first volume is, ultimately, a love story, the story of Tara and Thomas, her mounting despair at their inevitable separation, a separation caused by this uncanny repetition of time. Their love was never heightened by distance—it has always made them uncomfortable, to the point that they avoid long-distance phone calls when Tara travels to acquire books, “because such conversations seem to increase the distance between us,” Tara writes. “The conversation lapses imperceptibly into a kind of audio link, a muted love mumble.” Their love, microscopic in nature, depends on proximity and repetition. “For us it has always been about the days together, day after day, night after night, again and again. . . . There are no precipices or distances in our relationship. It is something else, a sort of cellular vertigo.”

Tara’s chronopathy is forcing those cells apart.

Book two, on the other hand, which begins in the second year of Tara’s eighteenths of Novembers, is about solitude. Thomas cannot help her out of her temporal room—she must go forth alone to figure out how to escape it; perhaps her keen eye for detail, so valuable when it came to assessing rare books, would help her find some glitch in the pattern that would afford her a doorway out. She returns to the scene of the crime, Paris, but she does not find it. Losing hope, she now longs for seasons, for qualitative difference in her days, and begins to travel—first, north, to find winter, in Sweden, in Norway, in Finland. She seeks spring in England, where unusually warm autumns have seen lambs anachronistically dotting the hills. She seeks summer in the balmy south of France. Finally, she gives this up, too, this effort to construct a “real” year, because, as a meteorologist she meets along the way points out, the seasons have nothing to do, actually, with time or its passing. Warmth is not bound to the months of June through August, the sound of snow slipping off the roof is not bound to March, they are just symptoms that occur, that humans tie into a chronology they invent for themselves. She stops searching, she lands in Düsseldorf and settles into her eighteenth of November, and waits.

It is a marvel that these short books contain so much—so many ways of measuring time and its effects, meditations on consumption and destruction, the quantum mechanics of love, the persistence of history and memory, the strange behavior of things in the world, how details appear at molecular and cosmic levels. But overall this is a work about writing, an act that is dependent, of course, on time. Tara herself depends on the healing potential of sentences, the repetition of phrases, the minute powers of words, to make sense of her new life. There is no narrative without the passage of time. We hear speech and it dissolves into the past; even if we write it down, to fix it in time, when we turn the page it disappears all the same. Readers scan sentences that begin and end, they scan pages that start and finish, then they turn the last page, and an entire world is gone.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.