Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

There once was a young man who dreamed of becoming

a master butcher . . .

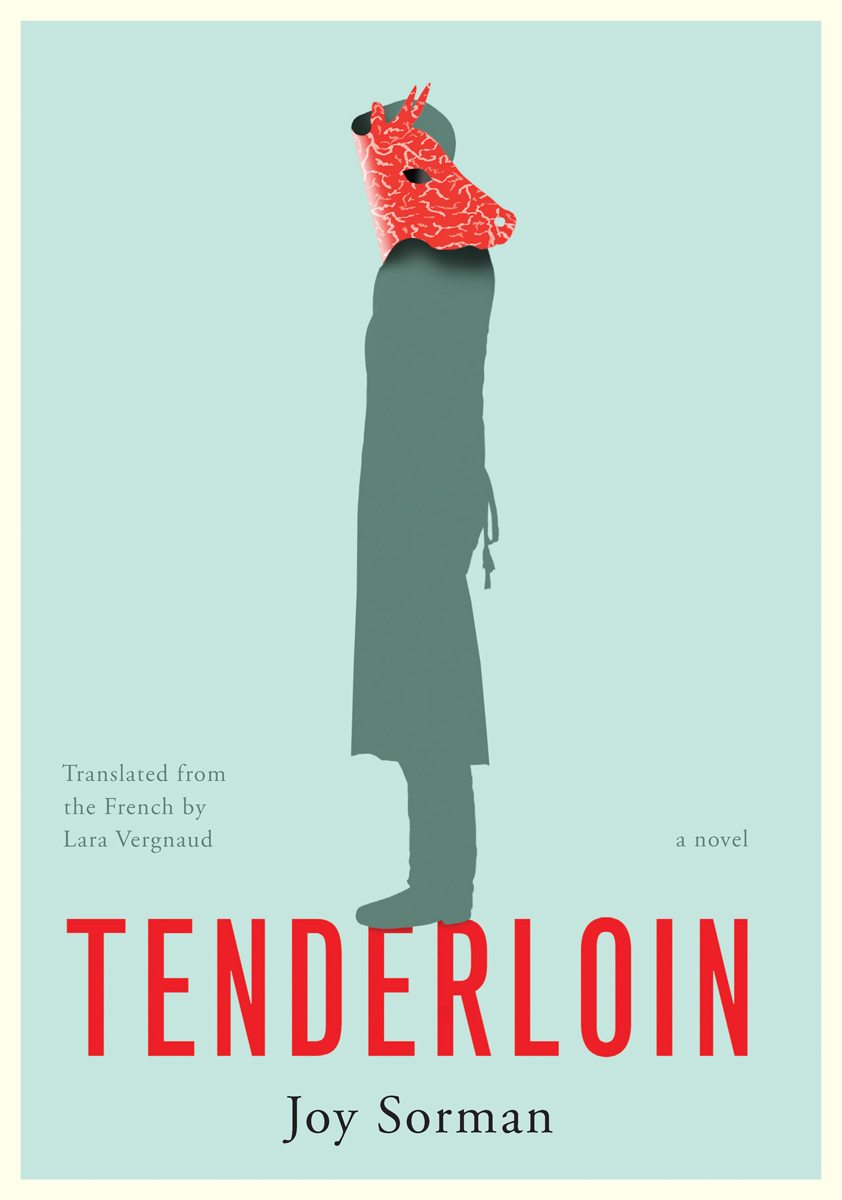

Tenderloin, by Joy Sorman, translated by Lara Vergnaud,

Restless Books, 165 pages, $18

• • •

The critic may experience many different feelings in their encounter with the art object; but for me, lurching nausea had never been one of them, until I read Joy Sorman’s Tenderloin, now appearing in English translation by Lara Vergnaud after its publication in French in 2012. At a slight 165 pages, it is an unassuming-looking novel, but it took me longer than average to read, as I queasily put it down every fifteen minutes or so. A tale of a butcher possessed by his craft, this is an extraordinarily pungent book—saturated with smells of blood, flesh, and effluvia in various degrees of freshness and decomposition, mingled with the odors of stale menthols and blistering Clorox, described in prose so precise my stomach kept flipping. It is just as potent visually, with its imagery of animals being stun-gunned in their vulnerable foreheads, strung up by their defenseless feet, the cutting of their recently screaming throats, the flaying of their once-protective skins, the wet slapping of their entrails onto conveyor belts, the sharp severing of their muscles from their bones. These muscles are sliced and pounded and tenderized into jewellike parcels, described by Sorman in engorged paragraphs detailing their sheen, textures, and colors as if they were Renaissance paintings, no longer recognizable as animal. In every drowsy, long-lashed cow there is the potential for an expertly seared filet mignon, and the author narrates each gory step of that transformation with words so unflinching and delectating that bile rose in my throat. All of which is to say, Tenderloin is an astonishing read.

We meet our protagonist, Pim, as a teen, pragmatically deciding not to pursue university studies but instead a trade, so that he may all the sooner start making money and get out of his dead-end town of Ploufragan, population eleven thousand, damply situated on the northwest coast of Brittany. Butchery is promised to be recession-proof, a steady and reliable trade, one that’s noble, too, for butchers are required to feed France, and they do it with art. We don’t learn too much about this “opaque young man,” except that he’s calm and good-natured, with a lean and acrobatic “body stretched out like a long vein,” possessed of lady-killing feline eyes and erotically dexterous hands. And that he has a mysterious condition that causes him to spontaneously weep—at the sight of his own hands, at the sight of a defenseless de-feathered chicken, at possibly anything at all, really, but always in the total absence of feeling. Does Pim feel anything, ever? The reader is unable to tell—Sorman’s character is a one-dimensional cipher, which gives her tiny but muscular novel the quality of a parable or a fable, an effect heightened by the book’s omniscient, unidentified first-person narrative voice.

Part one tracks Pim through his apprenticeship and early education in butchery, which sees him learning to prepare, with exponentially rising infatuation, different cuts of meat under the tutelage of a master butcher and then progressing swiftly backward in the food-production chain. There’s an extended chapter recounting a visit to a slaughterhouse, where the workers sing “I’ll never be / your beast of burden” on the killing floor, and then a summer spent interning on a dairy farm, learning to care for the animals he so loves to carve up, and where he forges an emotional (well, as emotional as it can get for Pim) connection with a gentle bovine called Culotte, named, it seems, for a particularly tender morsel of her flesh. Outside of his brutal tutelage, Pim has no friends, no other interests, besides the occasional sexual desire, consummated with Ploufragan adolescent girls driven wild by his eyes, whose bodies he maps out with his long nimble fingers, tracing the shank, the loin chop, the haunch, a whole anticipatory feast, to their shivering delight, at first, then creeping discomfort.

In part two, Pim has achieved his dream, he has become a master butcher with a wildly successful shop in Paris, his body has grown to resemble the once-living material he manipulates each day, his face mottled with rosacea, his delicate hands now meaty and swollen. His life has shrunk entirely to his devotion to butchery, though he still takes the occasional lover, lovers jealous of his obsession, one is even jealous of the meat itself, “a woman oppressed by meat, who has developed hang-ups because of meat, meat that is nothing more than a vain display of flesh in robust health, an explosion of life and if it spoils toss it to the stray dogs.”

Pim is not worried about this. What Pim wants is to get naked and rub himself against cow carcasses, to crawl inside them, to wrap himself up in the inanimate flesh, none of which he can do, due to hygienic concerns (the book’s account of the fatal consequences of meat gone bad is particularly stomach-churning). That his tears bear no trace of affect is the most obvious signal that Pim is all skin, no interiority, and this is the problem he longs to resolve, the problem, the narrator implies, we all long to resolve, at some level. What separates humans from nonhuman animals, Sorman suggests, is not our thumbs or our mental gymnastics, but our lack of insides, or maybe, rather, our shame about them, or their uselessness:

Animals are lucky, they’ve been granted an interior life, and Pim wishes he too could see what’s on the inside, that he could remove his own skin . . . Why settle for being an impermeable surface, Pim? Do you have a heart? a stomach? innards? On the scans, in the MRI, the images are hazy and opaque, the images are in black and white. . . . if our flesh was laid bare, we would suffer, we would weep, we would beg for mommy and someone call 911, because we’re fine being heaps of meat but we don’t want anyone to see.

Through all of this, Sorman manages to deftly and efficiently tease out questions of labor and class; industry, ecology, and public health; the moral value of nonhuman life. But where does she land on the ethics of carnivorism? This remains unclear, even in the book’s most direct address to the issue: “The vegetarians will need to win the battle, but they’re off to a rocky start seeing how the earth is swelling and demands to be fed, seeing how those too long nourished on dry bread and water wouldn’t mind, it’s only fair, a decent rib roast.” Her narrator extolls a preindustrial form of killing, in unnecessary, cringey passages romantically imagining Indigenous hunting practices, which inspire Pim in his ultimate frenzy of butchery in the book’s final pages, when “a carnivorous love pours out of him, an insensate gratitude for the animals he loves and eats, that he loves and kills.” Tenderloin is a uniquely powerful and persuasive piece of writing (all the more so for the intensity of its brackishness), but on this point, I am not persuaded—that killing a nonhuman animal for the sake of human appetite could ever be fair or necessary. Could ever be an act of love.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.