Ania Szremski

Ania Szremski

In the final poetry collection by Adam Zagajewski, memory shifts between the sorrow of loved ones lost and the gentle light of hope.

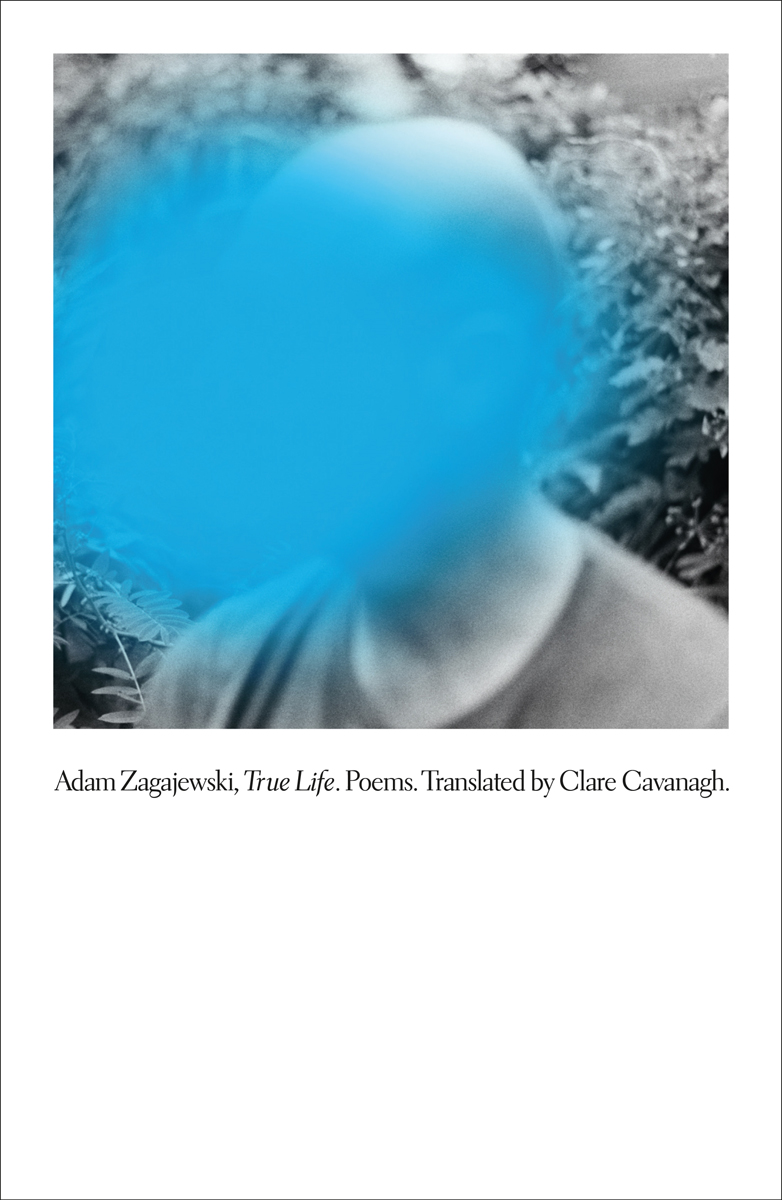

True Life, by Adam Zagajewski, translated by Clare Cavanagh,

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 63 pages, $13.99

• • •

Anyone writing about Adam Zagajewski after 2001 seems to feel obligated to foreground what would, that year, become his most famous poem, “Try to Praise the Mutilated World,” featured in the New Yorker’s 9/11 issue. When he died in 2021, at age seventy-five, one obituary called him “the poet of 9/11,” even though those lines were not really about 9/11 at all, having been written months before. Maybe it’s true of any poetry, but I think that especially when it comes to this Polish writer’s verse—his “slight exaggerations,” in his words; his “ordinary miracles,” to borrow a term from his compatriot Wisława Szymborska—his plain, slanted observations alter the world so that you cannot help but use them to describe the history of your own life, to trace the contours of your own memories, to give order to your own present. Just as much as he might be someone’s 9/11 poet, for me, sunflowers were written by him. For me, he is the poet of nettles, and waiting rooms, and looking through windows in cars and trains. And the poet of cats, who, arching their backs around an old woman with treats, reveal little pink tongues like orchids. He is the poet of walking down the street, listening to the past; he is the poet of September.

There will be a last time to see every person you know, and you don’t always know when it will be. Clare Cavanagh has been spinning Zagajewski’s poetry and books of essays into commonplace miracles of translation for going on thirty years, and she has done so for the last time with True Life, a collection published in Polish in 2019, now being posthumously issued in the US. Cavanagh wrote, in her own obituary of her friend, that she did not know these would be the last poems he would send her. Did he know? In a few of the pieces, he is in a hospital, and transforms something so unlovely as an IV drip into a sparkling object of interest, something that’s “transparent / as spring water / and never hurries.” It’s a collection filled with elegies and remembrances and dedications to loved ones, and reading it after his death, it can seem like a goodbye in that way. But then, his poetry has always been filled by those things. He had, in the cutting words of his elder, Poland’s most celebrated poet, Czesław Miłosz, that “privilege of coming from strange lands where it is difficult to escape history.” Born during World War II, Zagajewski’s perspective indeed never escaped history’s haunting, not only in the images he crafted, but also in his grammar. He so often wrote in the historical present, a paradoxical mode of capturing the past still alive in the immediacy, in the interiority, of the now.

In True Life, that now is sometimes located in the heavy, sulfurous month of September, “month of partings and rapture.” Partings—figures in Zagajewski’s poems are forever leaving; travelers, tourists, exiles, pilgrims, refugees ceaselessly move through his pages. Zagajewski is one of them. (“Only poets can live everywhere,” he writes.) Here, he is a boy, enticed by “the scent / of gasoline . . . Journeys smell like that.” The toxic perfume of freedom; he borrows an even better line from Czech author Vladimír Holan to describe it: “the scent of gasoline crickets,” inhaled as “people wait by the border / and look hopefully at the other side.” Places are what doesn’t move: cities, streets, churches, all implacable, are what stay behind. “The months came and left / discreetly, English-style. But streets stood motionless / . . . gazing in one direction only.” They travel solely when you carry them with you in your mind.

In Zagajewski’s earliest English-language collections, place can often be fuzzy, blurred, gray, made nameless by time, obscured by longing, by fog. In his poems from the ’80s, collected in English for 1991’s Canvas: “Cities at daybreak are no one’s / and have no names”; “you walk a street of lindens / but you don’t know which town’s. / You can’t remember in which country / gleam airy starlings”; “Night, an alien city, I roamed / a street with no name.” In True Life, a mid-lifetime later, the streets are precisely articulated, chattering with ghosts, and as the poet guides us down them, his lines sometimes sorrowfully shift to the simple past, verbs take on perfective aspects—even as memory sharpens, we’re plunged into the time of the no-longer. Zagajewski thus summons the bygone residents of “7 Arkońska Street”: “Mrs. Jodko, a beauty once, slowly / died of multiple sclerosis”; he drove, quickly, through the town of Sambor, where, he suddenly recalled, his mother passed her exams; at a bus stop, he remembers “that Andrzej Bursa used to live / right here, just outside.” Then, back in a kaleidoscopic, storytelling present, he is fifteen, and twelve, and also eighteen years old as he walks down Dworcowa Street in Silesia, lost. He travels east, sees “sunflowers with crumpled faces . . . Suddenly there’s Zamość, Leśmian’s home”; there’s Bełżec, “empty town inhabited / by half a million shadows, total silence of so many voices . . . it’s not far now / to final places, to origins, to the edge, / to black earth, to the aria with no end.”

But sometimes, it is also, beautifully, hopefully, May. “Famous May, / the month of promises / that nobody thinks to check later.” The yawing pain of history may perpetually quake in the world, but the world is also perpetually new. In Istanbul, he is happy, “for a moment, in the blaze / of a May day, watching.” This is why, probably, that famous poem, “Try to Praise the Mutilated World,” was a solace to so many. Zagajewski is always attuned to that dark, final place, but also, always, at the same time, to the “gentle light that strays and vanishes / and returns.” And he helps his reader see it, too. “Look, look greedily, / when dusk approaches, / look insatiably, / look without fear.”

Zagajewski’s words came to me unbidden so many times over the last year, which was a year of difficult losses, a year of writing eulogies, for different types of mothers in my life, most recently my mother-in-law. It’s like he was scripting what I saw, and making it more beautiful. I thought of his words late last summer, driving across eastern Romania, a time when normally your eyes would blur into dazzling lutescent streams, car windows refracting field after field of blazing sunflowers. But, in the last week of her life, they had all turned black, their burnt faces, weary, nodding toward the ground from stalks attenuated by drought. “I’ve seen sunflowers dangling / their heads at dusk, as if a careless hangman / had gone strolling through the gardens.” In the last week of her life, her son waited at the hospital, every day, in one office after another, persuading doctors to let him into the ward to see her. “Dusk fell / without funeral marches. / A lone colt danced on the highway, / though it didn’t stray far from the mare. / freedom is sweet, / so is a mother’s nearness.” Her husband sat at home, in a sitting room turned waiting room, listening to his phone’s silence. He “couldn’t say anything / and still can’t.” It was nearly September.

Ania Szremski is the senior editor of 4Columns.