Greg Tate

Greg Tate

In Sam Pollard’s documentary, Hoover versus King.

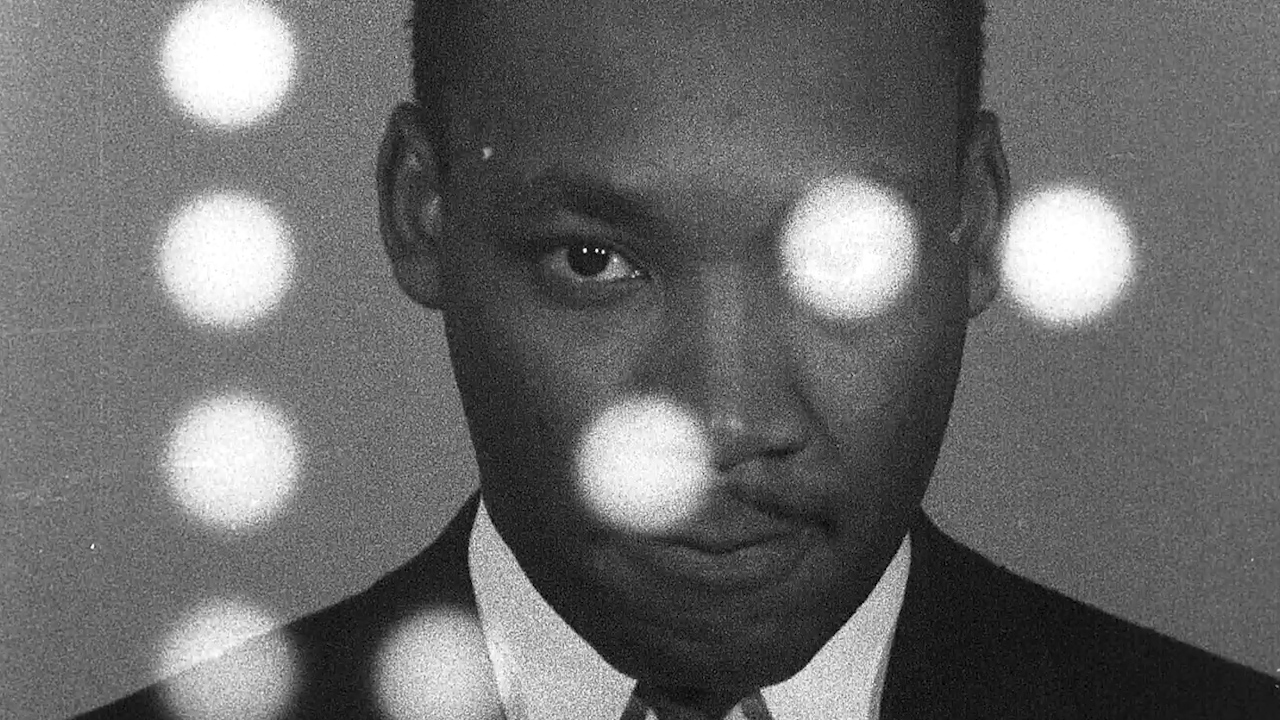

Dr. Martin Luther King in MLK/FBI. Courtesy IFC Films.

MLK/FBI, directed by Sam Pollard, available to rent on all major digital platforms and on cable VOD

• • •

Veteran documentarian Sam Pollard’s latest project, MLK/FBI, couldn’t have arrived at a more precipitous reckoning in the nation’s history—particularly given the attempted coup perpetrated in the new year’s first days by a well-organized militia under the sway and direction of the country’s forty-fifth president. Ostensibly an accounting of Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement leadership and the perversely obsessive attention his extramarital sex life drew from infamous FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, MLK/FBI also refers us back to a moment when the human rights of Americans and the Constitution were flagrantly violated by national police forces and the standing president.

MLK/FBI. Courtesy IFC Films.

Under Hoover’s direction, the bureau spent thousands of man-hours surveilling King and recording his encounters with women not his wife in hotel and motel rooms across the nation. As the film illustrates, agents were sometimes listening in from the room next door. That this went on from 1963 until King’s death marks his sexuality as a personal fetish for Hoover. Commentator and Hoover expert Beverly Gage contextualizes Hoover’s fixation on King’s on-the-road bedroom activities within the history of rape, lynching, and the demonizing of Black sexuality that began in slavery and remains a blaring feature of our popular culture today.

The film obliquely gestures toward well-documented knowledge of Hoover’s life as a closeted gay man who never prosecuted the Mafia because he feared extortion by the Mob for its knowledge of his homosexual domesticity with the FBI’s number two, Clyde Tolson. MLK/FBI does not engage with the research by Black American writer Millie McGhee claiming that Hoover was part of her bloodline and tacitly a self-hating Black man who spent his career “passing for white” and persecuting Black dissent—a psychoanalytical racial dream stew waiting to be stirred and dissected. Hoover believed the country’s number-one security threat at the height of the Cold War wasn’t Communism but “the rise of a Black Messiah.” After King’s death, Hoover intensified the efforts of his illegal COINTELPRO-Black Nationalist Hate Group program to systematically destroy the Black Panther Party with even more anti-constitutional fervor.

Pollard’s austere and sobering documentary—moodily abetted by composer Gerald Clayton’s ruminative underscoring—tightly focuses on Hoover’s various concerted attempts to use FBI resources to discredit King and the movement. At one point, the bureau sent King an anonymous letter threatening him with exposure while also incredulously and desperately advising him to kill himself.

As the film reveals, King’s capacity to soldier on while outwardly paying the Kennedy brothers and the FBI no nevermind was remarkable. Knowledge of FBI wiretaps, surveillance, infiltration, and leaks also failed to deter him from his unwavering, nonviolent, “eyes on the prize” pursuit of justice and opportunity for Blackfolk in Jim Crow America.

MLK/FBI. Courtesy IFC Films.

Mid-1960s USA was a time and place when mainstream domestic politics and news journalism were roiling with vestigial anti-Communist hysteria and paranoia. Many Black Americans believed proving their patriotism required them to openly abhor Communism. Some movement spokespersons anxiously denied any association with American Marxists. One acute measure of King’s fortitude was his refusal to discontinue a mentorship and counseling relationship with a former member of the US Communist Party, Stanley Levison. Both Kennedy brothers strongly urged King to distance himself from Levison, which he agreed to but, in actuality, never followed through on.

Pollard assembles a narrow circle of King colleagues and historians as his co-respondents. The specter haunting MLK/FBI is the reveal that in 2027 the FBI’s scurrilous audio files, now in the National Archives, will be made available to the public. The question of whether these tapes will change the perception of King’s legacy is unequivocally dismissed onscreen by his colleagues Clarence Jones and Andrew Young; scholars Gage and Donna Murch remain confident that King’s personal life can be readily separated from his activism. Voluminous King historian David Garrow is more ambivalent and circumspect in his response.

MLK/FBI. Courtesy IFC Films.

The film requires younger viewers to imagine a time when the sexual transgressions of political figures could be deemed shocking and exploitable. It also captures a seismically transformative moment when the nation, seemingly overnight, became starkly and venomously polarized between those who openly opposed White House policy and those who blindly and quite rabidly supported all Oval Office directives as the raging epitome of patriotism.

King and President Lyndon Johnson were in daily, congenial collaboration in pushing the historic 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act though Congress and into national law. Their relationship soured soon afterward over King’s opposition to America’s war in Vietnam. In the film we learn that King, a critic of the war as early as 1965, censored himself for eighteen months after his advisers expressed apprehension that blowback would derail the movement’s legislative agenda. When King unmuted himself on the subject in 1967, he became nearly a mortal enemy to the gung-ho LBJ.

Dr. Martin Luther King in MLK/FBI. Courtesy IFC Films.

Hoover used the split to cozy up to the president, now finally a fellow King adversary. Not long after King’s assassination, Johnson, under heavy fire from his own party and bombarded by the widely televised chants of the anti-war movement (“Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?!”), withdrew from the 1968 presidential race. In the year before he was killed, however, King confronted intensified attacks not only from Hoover and the Johnson administration but from within the movement as well. More conservative, bootlicking types assured the establishment that the movement considered American foreign policy above a negro activist’s pay grade.

Dr. Martin Luther King in MLK/FBI. Courtesy IFC Films.

Addressed toward the end of the film is the question, asked within the bureau at the time and posed by Pollard to former agents today, of why the FBI, given its round-the-clock, intimate surveillance of King, apparently had no inkling that he was being stalked and targeted for assassination by a known criminal and white supremacist. Young goes on record as saying he doesn’t believe the convicted shooter, James Earl Ray, was guilty. And the evidence presented about Ray, a petty thug of limited means who gained access to multiple false passports to compel an international manhunt, suggests he was anything but the proverbial “lone gunman” lacking in resourceful accomplices.

MLK/FBI’s transparent resonance with present-day, government-sponsored anti-Blackness and unconstitutional assaults on lawful dissent is superbly framed and crafted, and undeniably astute.

Greg Tate is a writer and musician who lives in Harlem and is a proud member of Howard University’s Bison Nation. His books include Flyboy in the Buttermilk, Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix and the Black Experience, Everything but the Burden: What White People Are Taking from Black Culture, and Flyboy 2: The Greg Tate Reader. Since 1999 Tate has also co-led the Conducted Improvisation ensemble Burnt Sugar the Arkestra Chamber. The group tours internationally, and has released sixteen albums on its own AvantGroidd imprint.