Andrew Uroskie

Andrew Uroskie

The Whitney Museum’s sprawling new show surveys a long, complicated relationship.

Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun, 2015. High-definition video, color, sound, dimensions variable. Image courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery. Photo: Sarah Wilmer.

Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016, the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, New York, through February 5, 2017

• • •

The sheer breadth of Dreamlands belies snap judgments. Featuring over one hundred artists whose works span more than a century, curator Chrissie Iles’s ambitious, sprawling exhibition contains everything from traditional cartoon animation to 3-D environments, assemblage film to interactive AI. The Whitney’s entire fifth floor is filled with work, and twenty-five additional days of screenings and performances take place in the museum’s third-floor theater, and off-site at the Microscope Gallery and the Knockdown Center in Bushwick. These performances and screenings extend the scope and impact of the main exhibition in innumerable ways, providing context and elaboration for the show’s principal themes.

Dreamlands will inevitably be compared to Iles’s relatively delimited Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 1964–77 (Whitney, 2001), but it more closely resembles Kerry Brougher’s expansive surveys Art and Film Since 1945 (Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, 1996) and The Cinema Effect (Hirshhorn, 2008)—broad attempts to assay cinema’s irrevocable transformation of modern perception and subjectivity.

The complicated relationship between cinema and modern art has long constituted a vexing problem for historians and critics, in part because cinema cannot help but overflow its bounds, not only appropriating other practices, but continually leaking out into the domain of cultural life more generally.

This fluidity and heterogeneity are precisely what fascinates Iles, as we see immediately upon entering and encountering a wall-sized video projection of Triadic Ballet by the Bauhaus multimedia artist Oskar Schlemmer. It is a provocative choice with which to begin the exhibition: a 1922 choreography of mechanical movements in an abstracted space, here presented in a filmed re-performance from 1970 and recently digitized for exhibition.

After Oskar Schlemmer, Das Triadische Ballett (Triadic Ballet), 1970. 35 mm film transferred to video, color, sound. Image courtesy Global Screen, Munich.

Is this a work of dance, film, or video? To what historical period do we assign it? The complexity of such questions serves to succinctly encapsulate experimental cinema’s distinctly non-linear genealogy: the manner in which so much of the 1920s avant-garde would be rediscovered by artists of the postwar period, just as intermedia practices of the 1960s and 1970s have been rediscovered by artists since the late 1990s.

On the opposite wall, Edwin Porter’s Coney Island at Night (1905) presents an almost unedited recording of the famous Dreamland park in which space is similarly abstracted: the obdurate solidity of architecture dematerialized into spectacle through over a million incandescent lights.

Porter’s film is silent; across the room we overhear a third instance of documentation: a recording of Neil Armstrong recounting his first steps on the moon in Pierre Huyghe’s video One Million Kingdoms (2001). A ghostly young girl travels through a third abstract landscape: a computer-generated visualization of the astronaut’s voice. Part of the larger project No Ghost Just a Shell (1999-2002), Huyghe’s work is but one of eight pieces in the exhibition featuring Annlee, a Japanese manga character he and fellow artist Philippe Parreno purchased and made freely available for collective appropriation.

The three works in this opening room—made with film, video, and the computational image—trace cinema’s technological past and future, while addressing several of its most pervasive effects and concerns: the dissolution of a sense of place, the changing character of documentation, and the transformation of the self through the creation of alternate phantasmatic realities.

At its best, the exhibition facilitates these kind of thoughtful juxtapositions. Rather than individually curtained black boxes, walls are often left half-open, sight-lines and sound-spill seeking to provoke new associations and correspondences. It is a curatorial strategy echoed in the reconstruction of Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie Mural (1968), the show’s largest and most complex audiovisual installation.

Stan VanDerBeek, Movie Mural, 1968. Multiple 35 mm and 16 mm films transferred to video, with black-and-white and color slide projections. Image courtesy estate of Stan VanDerBeek. Photo: Andrew V. Uroskie.

Ektagraphic slides and digital projectors together form a living montage of still and moving imagery across a wall of screens. Art historical and photojournalistic imagery collide with the artist’s own works of animated collage, videographic dance, and computational poetics. And at the center of this maelstrom, the image of a death’s-head moth on a spider web remains fixed by an overhead projector. That projector poignantly marks the limits of historical reconstruction, having originally served as a means by which VanDerBeek could draw and paint on projected transparencies during an ever-changing performance.

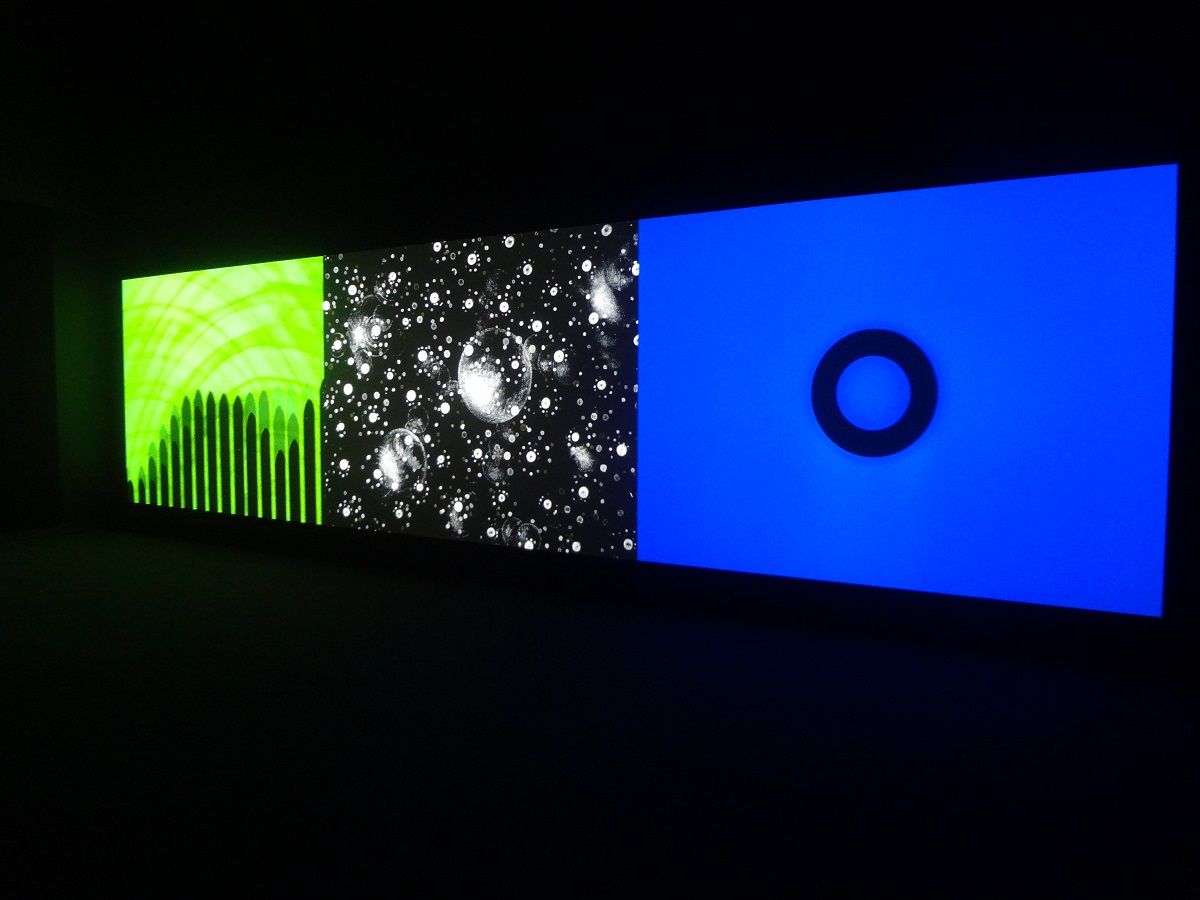

This model of environmental, multi-projector performance was pioneered four decades before in such works as Oskar Fischinger’s Raumlichtkunst (Space Light Art, 1926/2012), on view nearby. Painstakingly reconstructed by the Center for Visual Music from films more than half a century old, this three-screen video installation is a kinetic abstraction of psychedelic color and intensity, contrasting geometrically thrusting bars with centrifugally collapsing folds, as central images of the cosmos evoke the infinite.

Oskar Fischinger, Raumlichtkunst (Space Light Art), 1926/2012. 3-screen projection. Image courtesy Center for Visual Music.

Fischinger’s contemporary Kurt Schwerdtfeger was similarly enmeshed in ideas of kinetic abstraction, and an extraordinary performance of the artist’s Reflektorische Farblichtspiele (Reflecting Color-Light-Play, 1922/2016) took place off-site at Brooklyn’s Microscope Gallery. First, Schwerdtfeger’s projection apparatus had to be reconstructed: a kind of color organ using an array of stage lights and colored gels to variously illuminate a translucent scrim from behind. A fiberboard stencil with cut-out shapes and adjustable sliding panels was then placed between the lights and the scrim. While one operator controlled position, color, and the number of lights shining on the scrim, two other operators moved the panels back and forth over the cutouts like the opening and closing of an aperture. Over six “movements,” the basic shapes of six stencils were modulated into seemingly endless variations by means of spatial displacement and a constant iteration of form and color.

Kurt Schwerdtfeger, Reflektorische Farblichtspiele (Reflecting Color-Light-Play), 1922/2016. Constructed by Daniel Wapner, performed by Lary 7, Bradley Eros, Rachael Guma, and Joel Schlemowitz at Microscope Gallery. Image courtesy of Microscope Gallery and the Kurt Schwerdtfeger Estate.

As is inevitable with a show of this size, questions will be raised as to the criteria by which certain artists were included or excluded, as well as the rationale for staging certain works as installations within the gallery, while grouping together others within supplemental screenings. This seems only appropriate in an exhibition designed more to provoke and question than to stage a particular polemic.

Even as contemporary media art has become increasingly ubiquitous, historically canonical works like VanDerBeek’s Movie Mural or Schwerdtfeger’s Reflecting Color-Light-Play are very rarely exhibited; they are typically consigned to archives or storage vaults and are only vaguely accessible through documentation. Evading the financially inflationary forces of the art market, the restoration and exhibition of these works is a labor of love for curators, preservationists, and museum boards. In gathering such a polyphony of voices past and present, the installations, screenings, and performances in Dreamlands offer a welcome corrective to the art market’s myopic focus on the present.

Andrew Uroskie is the author of Between the Black Box and the White Cube: Expanded Cinema and Postwar Art (University of Chicago Press, 2014). He serves as Associate Professor of Modern Art and Media at Stony Brook University in New York, where he directs the MA/PhD Program in Art History & Criticism. His new book project The Kinetic Imaginary was awarded a 2016 Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant.