David Schurman Wallace

David Schurman Wallace

In Elif Batuman’s sequel to The Idiot, a second year of love, sex,

and books.

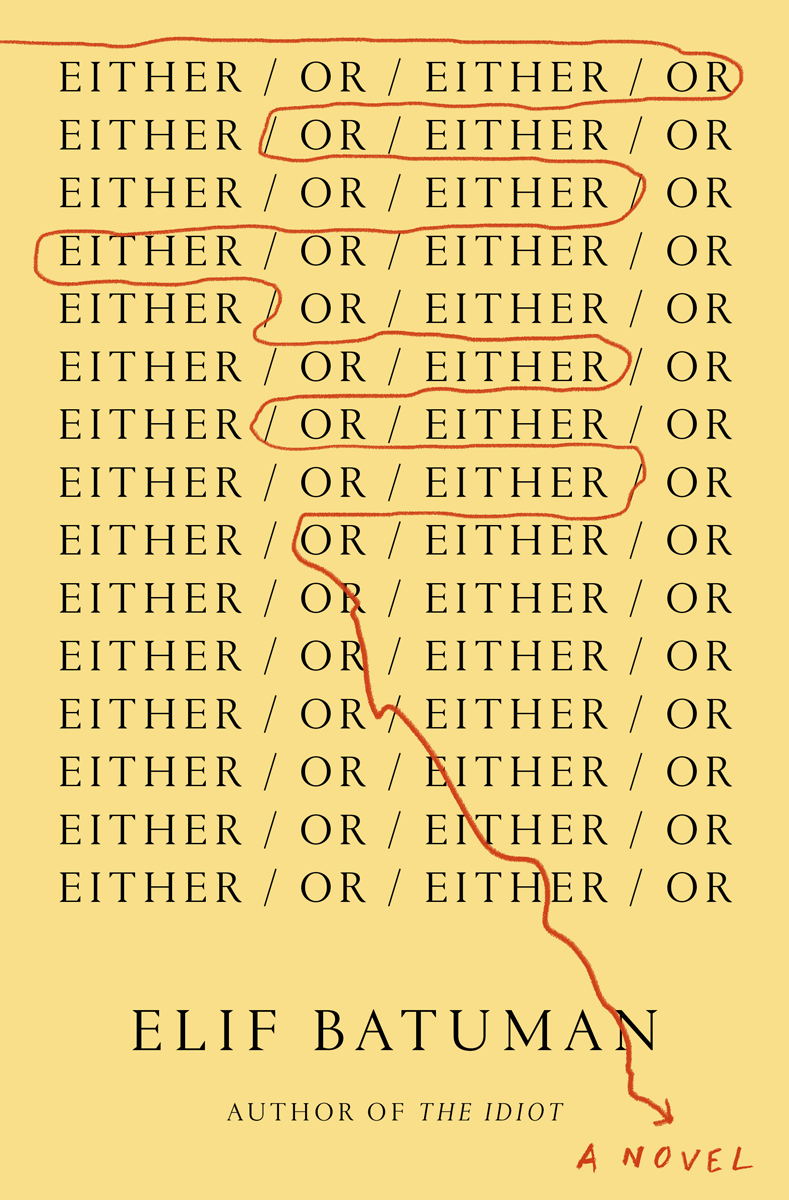

Either/Or, by Elif Batuman, Penguin Press, 360 pages, $27

• • •

In the acknowledgements of The Idiot, Elif Batuman’s first novel, she notes that the book, although published in 2017, began as a rough draft in 2000. This dates the birth of the project, a very funny, at times brilliant, chronicle of her Harvard-freshman experience, to shortly after her own Harvard graduation. What began as a kind of autofiction was changed by incubation, as the interval grew between the writing and its source. It was only later, Batuman writes, that she “discovered that time had turned it into a historical novel.”

All fictions, auto or otherwise, that painstakingly detail their present will become time capsules. Today’s “extremely online” novel will feature in some New–New Historicist’s thesis, with tenure dispensed for elucidating “goblin mode.” Batuman’s great subject as a writer is how life and literature come together—or don’t. Accordingly, the undergraduate experience of Selin, Batuman’s surrogate character, consists of two major components: reading lots of books and trying to decipher the enigmas of love and sex. The reader is asked to compare: When is a book like life, and life like a book? But perhaps lurking behind this lofty question is a more technical one. Is that meticulous attention to detail the essence of the “voice,” the thing that makes a book vivid after events fade into the past?

Either/Or, Batuman’s follow-up to The Idiot, cannot be understood without its predecessor. Picking up immediately where the first book finished—sophomore year—there’s something surprising in such a direct sequel. Another author might flash Selin forward, imagining her at commencement or starting her first post-collegiate job. In The Idiot, there was a resoluteness, even pride, in never tying a narrative bow on the “pointless, shapeless days.” Either/Or returns to the granularity of dining hall sessions, ancillary roommate dramas, fleeting romantic entanglements, and of course numerous texts read and considered. Early on, Selin reflects on her strengths as a writer, justifying this method of recording reality’s contours:

I realized, with shock, that I wasn’t good at creative writing. I was good at grammar and arguing, at remembering things people said, and at making stressful situations seem funny. But it turned out these weren’t the skills you needed in order to invent quirky people and give them arcs of desire. I already had my hands full writing about the people I actually knew, and all the things they said. That was what I needed writing for.

Even the most minute experience is worth chronicling if Batuman’s eye for absurdity can find some purchase. This commitment to “real life,” both praised and criticized in The Idiot, also had the beneficial side effect of suspense. Why was Selin in the Hungarian countryside, teaching English for reasons barely understandable to herself? Would things ever heat up with Ivan, her Hungarian love interest? Like life, anything could happen next, but this fidelity also left the reader in the lurch, abruptly breaking off a richly realized narrative. How, then, to continue?

Unfortunately, it’s rare to have a second decades-old manuscript lying around. This leaves Batuman with the curiously historical task of how to recreate the same voice at an even greater remove. While Batuman is remarkable at conjuring experiences now solidly in “lost time,” the sharpness of Either/Or can seem slightly turned down, perhaps suffering from the unusual situation of there being another novel so similar—her own. None of the new cast of characters quite matches Ivan or Svetlana, the strong-willed Serbian analysand who was Selin’s freshman foil. In another tantalizing back-of-the-book note, this time in the sequel, Batuman mentions the influence of Adrienne Rich’s “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” an essay she admits to not reading (and having no interest in) as an undergraduate. However, this suggestion of infusing a contemporary perspective only ever hovers around the margins. Is Selin attracted to Svetlana? Perhaps, but what is presumably a compulsion to invent as little as possible restrains further investigations. When Svetlana pairs off with a dull boyfriend and disappears, as freshman friends can, I mourned for that missing “arc of desire” that fiction might supply.

As Selin remarks to herself in The Idiot, writing’s power “wasn’t just to record something past but also to prolong the present, like One Thousand and One Nights, to stretch out the time until the next thing happened.” Like Marcel Proust or Henry James, then, Batuman’s power is to dilate time. Because her voice is so precise and assured, it’s easy to want to live alongside it—when Selin skewers the banalities of tour-guide writing, for instance, there’s a sense that you would let Batuman read you numbers out of a phone book. At the same time, this commitment to placing events under the microscope can be risky. One visit to college is a bildungsroman, two is a preoccupation. If we imagine a pace of one longish novel per undergraduate year, the result could possibly be the most exhaustive Ivy League tribute ever. And I’m sure there’s some fierce competition.

Can great books ground a good life? Either/Or doesn’t seem particularly interested in answering that question, which remains rhetorical, but another formidable syllabus is assembled. Not least is the Kierkegaard work of the same name. In particular, “The Seducer’s Diary,” its book-within-the-book, becomes Selin’s key to understanding the withheld affections of Ivan. More broadly, Kierkegaard’s distinction between living an ethical life and an aesthetic one is taken up as a theme that loosely structures events, though the aesthetic triumphs without too much struggle. Batuman’s penchant for writing over canonical titles (this is her first deviation after two bouts with Dostoevsky) is itself an attempt to bridge the life/literature divide: a way to superimpose oneself on the dead-male Western canon with élan. To challenge tradition, but always remain fundamentally respectful of its authority—the demeanor of a star student.

Despite a certain sense of Repetition—to continue borrowing from Kierkegaard—the pleasures of Either/Or, if taken on its terms, are considerable. The second half opens onto sexual discovery (deferred for the previous six hundred or so pages), the pains and anticlimaxes of which Batuman renders with great sensitivity. A trip to central Turkey for Harvard’s student guidebook is both touching and harrowing—in the “and then” of the travel essay, she’s in her element. And it’s a treat to hear Batuman’s thoughts about nearly any work of literature, from André Breton’s Nadja to James’s Portrait of a Lady, the novel that inspires Selin to throw down her gauntlet: “to remember, or discover, where everything came from.”

As an undergraduate, I was taught about the Russian Formalist distinction of fabula and syuzhet—roughly, the difference between the chronological sequence of events “as they happened” and the order in which they’re presented in narrative. Though Russian Formalism is mentioned more than once in the novel, Batuman makes little effort to disrupt chronology. Despite the impressive (if concealed) technique required to reconstruct the past, in many ways the book is resolutely non-formalist: anecdotes are stacked up in order, day by day, semester by semester. All the books that Selin is imbibing, all complex in their various ways, supply the fictional tool kit not directly forthcoming from Batuman.

But perhaps typical ideas about narrative progress are absorbed too easily by critics, too: we ask authors to improve, challenge themselves, not repeat the same trick. Selin’s second act might not be the advance one hoped for, but that was never promised in the first place. Batuman is still investigating how experience transforms, how that everyday shapelessness starts to feel like something inevitable. So far, no conclusion. But in the meantime—in the spirit of the aesthetic life—why not live inside the style?

David Schurman Wallace is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, the Nation, the Baffler, and the Drift. Formerly a fiction editor at the New Yorker, he is at work on a nonfiction book.