Seth Colter Walls

Seth Colter Walls

The veteran musician-composer still delivers—and inspires—fresh sound-worlds.

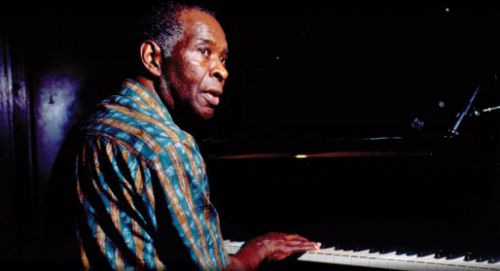

Muhal Richard Abrams. Image courtesy AACM Chicago.

Muhal Richard Abrams Trio / Bluiett Music, The Community Church of New York, October 28, 2016

• • •

Muhal Richard Abrams is one of the most matter-of-fact radicals in the world of contemporary music. The veteran composer, pianist, and educator can answer journalists’ questions with a bemused quality, sounding as though he’s not certain why his insights should stir such fascination. When speaking with the critic Frank J. Oteri earlier this year, Abrams uncorked one of his humble aperçus: “individualism is not something that’s strange. You know what I mean?”

Perhaps. Still, there is something particular about the force of Abrams’s vision. As one of the co-founders of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM)—a 1960s collective born in Chicago that has also long been active in New York—Abrams directly mentored a generation of artists that includes the MacArthur “genius grant” recipient Anthony Braxton and the Pulitzer prize-winning composer Henry Threadgill. (Both saxophonist-composers appear on Abrams’s 1977 album 1-OQA+19.)

Abrams’s store of recordings includes idiosyncratic solo essays, as well as imaginative big band sessions that can reference vintage forms of jazz (as on Blues Forever) while simultaneously exploring modernist harmony and synthesizer timbres (on the album Blu Blu Blu). Abrams’s music has roots in the American jazz tradition as well as in his study of the Western classical canon. And the pianist sees no need to define his approach as dominated by one genre heading or the other, preferring instead the term “creative music.” (A terminology that is enshrined in the AACM’s very name.) This attitude has flummoxed some critics and polemicists. More consequentially, Abrams’s example has had a pronounced effect on the last half-century of American art music.

The eighty-six-year-old’s most recent concert showed that his experimental spirit is still thriving. On the final night of a month-long AACM concert series at the Community Church of New York’s large and resonant Hall of Worship, the pianist presented a new trio that included two much younger musicians: violinist Tom Chiu and cellist Meaghan Burke. In their company, Abrams delivered a fresh sound-world that recalled no obvious reference point from his vast discography. The forty-minute set was devoted to a piece with the casual title “Trio Things.” But the performance suggested plenty of forethought, as well as live-wire inspiration—blending improvisation and written-out themes in a gripping, persuasive swirl of textures.

Abrams started out alone, with a passage of rumbling, often droning playing that focused on some of his instrument’s lowest keys. It wasn’t a pianism meant to stun with dexterous, easily followed lines; it was more environmental in nature. Gradually, Abrams allowed a melodic scale to rise from this density. Then, with his right hand, he produced quick arpeggios in a higher octave—a signal for the string players to enter, playing music that used some of the same intervals.

This division of labor established the early structure of the piece. Initially, Abrams and the string duo played in discrete sections, meeting only at the transition points. In their first mutual feature, Chiu and Burke played from scores, creating attractive harmonies and febrile syncopations. (For his part, the pianist performed without a score through the entire set.) As the piece continued, the trio entered into a more developed dialogue—with Abrams adding dizzying, well-timed lines to a section of pointillist writing for the violin and cello. And when the string players joined Abrams-led sections, they seemed to be paying more attention to the pianist than to the printed material on their music stands.

Chiu and Burke brought a variety of strategies to bear on the set: some initial music required lustrous vibrato expressions, while later passages elicited harsher attacks. Subtle amplification of the group was well handled by the event’s sound technicians, allowing the grain of harder-edged bowing and pizzicato exclamations to be easily distinguished, next to Abrams’s booming piano. In the final minutes, Abrams created a dramatic change, with two-hand patterns that spiraled out from the piano’s center to both extremes of the keyboard. The string players responded with exaggerated glissando figures before allowing Abrams one final solo statement. The pianist concluded the performance with a barnstorming, descending run of cluster chords that decayed slowly in the church’s vast acoustic space.

Unlike some of Abrams’s past experiments, there was only the barest trace of blues in this performance. But the balance of design and freedom in the piece had the attitude of progressive jazz, even when minutes of static harmony or chattering complexity brought to mind classical composers as different as Morton Feldman and Helmut Lachenmann. As with my prior experience of an Abrams concert, at Brooklyn’s Roulette in 2013, I found myself surprised by the unpredictable quality of the music—and also wishing that I could take a recording home.

The concert’s second set, from a group led by baritone sax titan Hamiet Bluiett, created a different form of ecstasy. His band included the virtuoso pianist D.D. Jackson and the rising-star tenor sax player James Brandon Lewis—and it followed a looser program that dug deeper into traditional blues textures. The group created a surging sense of catharsis in the first ten minutes, drawing feverish cheers from the audience. This fiery, frequently hard-swinging performance threatened to peak too early, though Bluiett’s seat-of-pants band-leading created plenty of tension and release throughout the balance of the set.

As is often the case with AACM events, there was a warm feeling of community in the room. In between sets, I observed D.D. Jackson approaching Abrams. Though I didn’t want to horn in on their conversation, I could hear Abrams answering the younger pianist’s inquiry about the blending of written parts and improvisation. So even Jackson—himself an accomplished arranger and guest musician who has worked with the Roots—was there, at least in part, to learn from an elder.

While Abrams hasn’t issued an official recording since 2011’s meditative, electro-acoustic SoundDance, it’s obvious that he still has plenty of ideas left to articulate. At the end of the show, an announcer noted that Abrams would be leading free-to-the-public, open rehearsals of some new orchestra pieces this December. The storied educator’s method of instruction-by-example continues.

Seth Colter Walls is a critic and reporter whose writing on music, books, and film has appeared in The Guardian, Pitchfork, The Village Voice, and The London Review of Books. He is the author of the novel Gaza, Wyoming.