Elvia Wilk

Elvia Wilk

In the artist’s solo show at The 8th Floor, a danger zone lies in the space between language and bodies.

Bang Geul Han: Land of Tenderness, installation view. Courtesy The 8th Floor. Photo: Adam Reich.

Bang Geul Han: Land of Tenderness, curated by Anjuli Nanda Diamond and George Bolster, presented by the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, The 8th Floor, 17 West Seventeenth Street, New York City,

through May 13, 2023

• • •

I walked to Bang Geul Han’s solo show, Land of Tenderness, after leaving my therapist’s office. Entering the gallery, the first artwork that greeted me was a series of ninety-one multicolored macramé bracelets lined up on a long, low plinth—the type of bracelets I used to knot at summer camp for my adolescent BFFs. Words are woven into them, and these were the first I read:

THOUGH I’M TRYING

TO DO BETTER

I KNOW I HAVE

LONG WAY TO GO

**THAT IS**

MY COMMITMENT

MY JOURNEY NOW

WILL BE TO

LearnAboutMyself

CONQUER MY

<3 DEMONS <3

Oh no, I thought, recalling my therapy session and cringing. I do need to learn about myself and conquer my demons. I am trying to do better! Forgive me!

Bang Geul Han, Apology Bracelets (Harvey), 2022. Cotton embroidery floss. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Argenis Apolinario.

I didn’t know before reading the wall label that the work is called Apology Bracelets (Harvey) (2022), which certainly changed my interpretation, as I’m sure it just changed yours. The snippets of text turn out to be phrases Weinstein used in his public apology statements after the infamous revelations of 2017. Oh no, I thought again. My inner monologue sounds like Harvey Weinstein? Perhaps, I reflected, we’re all reduced to stock phrases even at our most intimate, vulnerable moments. Perhaps we’re all implicated in the hollowing of language, which is what allows power to hide behind euphemism. These innocent-looking bracelets had slyly led me into a danger zone.

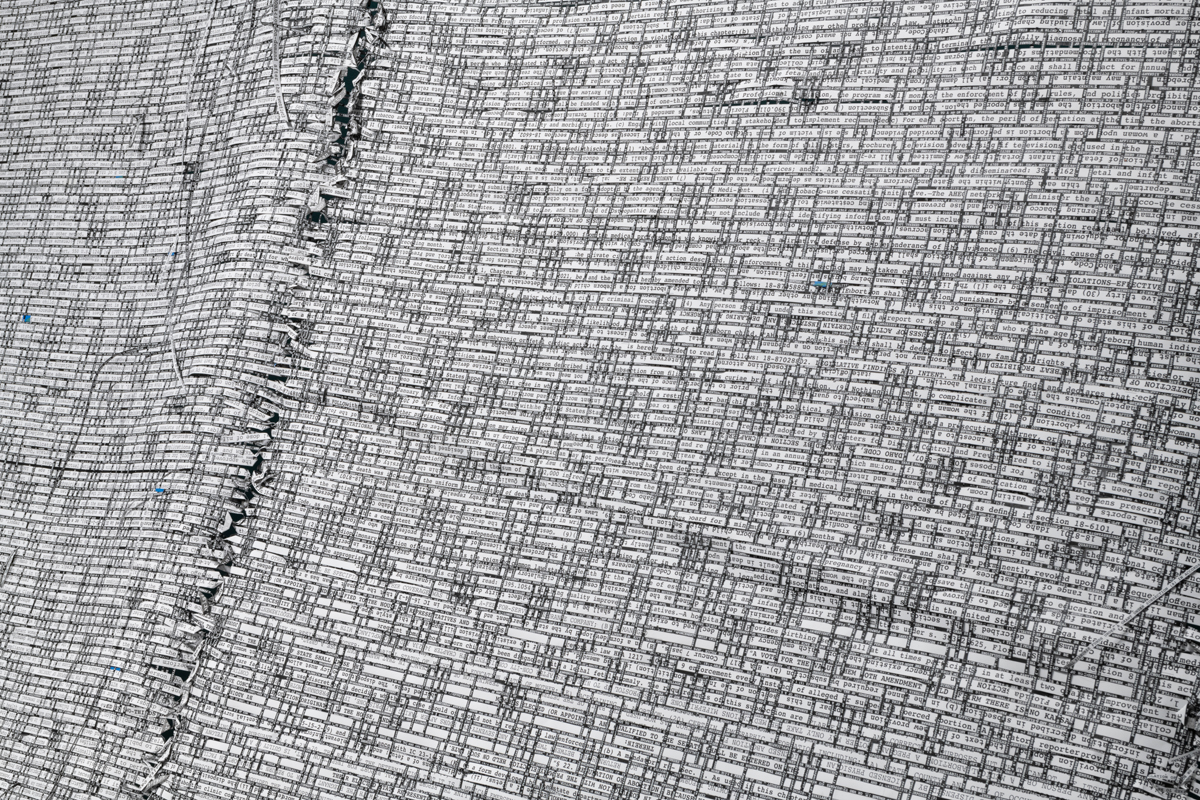

Bang Geul Han: Land of Tenderness, installation view. Courtesy The 8th Floor. Photo: Adam Reich. Pictured, left to right: Warp and Weft #02, 2022; Warp and Weft #05, 2022; Warp and Weft #03, 2022.

I was glad I hadn’t read the caption first. I had inserted myself into the narrative, a self-indulgence as illuminating as embarrassing. I decided to do a lap around the rest of the exhibition before reading any other labels. I rarely make a point of avoiding such texts—it would seem like clinging to some idea of “unmediated” interaction, which is silly if not futile once you’re already in the white cube—but I was glad I made the choice here. It revealed that the works in the show have an uneven reliance on supporting material, a relationship that tends to be consistent across a solo exhibition. I found this unexpectedly fitting for a show that is fundamentally about the power dynamics, bodies, and violence that can be obscured by an excess of language.

Bang Geul Han: Land of Tenderness, installation view. Courtesy The 8th Floor. Photo: Adam Reich. Pictured: Warp and Weft #05, 2022 (detail). Woven paper tapestry, metal rod, thread.

My attention was next commanded by four tapestries woven from long strips of paper printed with writing in bureaucratic serif typefaces. They’re intricate, meticulous crafts, hung from rods and strings, with bumpy edges and loose dangling ends. One is draped majestically from floor to ceiling. When you step close, you can make out partially obscured phrases like: “SECTION 46.206 OF TITLE 45”; “PROSECUTED”; and “PROHIBIT CERTAIN ABORTION.” Unlike with the Weinstein piece, you know, without knowing the source material, that this is politicized and gruesome stuff. On my second lap, I learned that all four are titled a variant of Warp and Weft, and captions expand on the citations. For Warp and Weft #01 (2021), warp is “The Office of Refuge Resettlement’s spreadsheet tracking migrant minors’ pregnancies from 2017–2019,” and weft is “Section 209 of the Department of Labor and Health, Education, and Welfare Appropriation Act of 1977 . . . dissenting opinion by Justice B. Kavanaugh.” The contrast of tedium and suffering here immediately called to mind a piece by Emily Barker: Death by 7,865 Paper Cuts (2019), a tower of the artist’s own xeroxed medical bills adding up to hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt. Both Barker and Han show how grave injury, trauma, and assault can be reduced to a series of infuriating clauses, keywords, and procedural codes. Three photographs accompanying the weavings portray Han shrouded in her text-textiles in domestic settings: reading on the toilet or supine in bed. These vulnerable, quietly funny images allow a body to peek out from behind the paperwork.

Bang Geul Han: Land of Tenderness, installation view. Courtesy The 8th Floor. Photo: Adam Reich. Pictured, left: Warp and Weft #02 – Toilet, 2022. Right: Warp and Weft #05, 2022.

The bracelets, weavings, and photographs support one another both thematically and aesthetically, as do their labels, making them intertextual in the truest sense. But two videos and two VR works also displayed in Land of Tenderness feel like a distinctly separate body of work. Their aesthetic vocabulary is radically different, and it’s more challenging to engage with them without resorting to the wall text, the opposite of how I had felt with the object pieces, which are complicated by their labels but not dependent on them. The VR project after which the exhibition is named, Terre de Tendre (Land of Tenderness) (2023), is shown on a Meta Quest 2 headset. It begins in a room where the user can pick up objects, such as a TSA-approved luggage bin, coming down a conveyor belt. The interactivity is limited and tricky to figure out without directions. Next, the room breaks open and the user is floating in a seascape surrounded by enormous mountains coated with what appears to be stock footage of, e.g., manicured hands cleaning a teakettle; there’s also flying Word-art-style text (“DANGEROUS SEA”) and what I learned is a theme-park soundtrack. I got nauseated (as an extra wall label warns might happen) and had to take a break. I suppose this is appropriate for an artwork that (the wall text implies) reflects the terror and disorientation of forced migration. The text also explains that the project is inspired by the Carte de Tendre, an “allegorical map created by a group of women in 17th century France, which charted the emotional path to true love.” While this is an awesome reference point that I recommend Googling, I can’t quite articulate its relationship to my firsthand experience in the headset.

Bang Geul Han: Land of Tenderness, installation view. Courtesy The 8th Floor. Photo: Adam Reich. Pictured, left: Terre de Tendre, For Someone Else, For Somewhere Else, 2023. Right: Terre de Tendre (Land of Tenderness), 2023.

One other piece, a sculpture, stands in its own material-aesthetic category. Threshold (2022) is a wooden doorway. LED text slowly scrolls along its bottom plank: “GEST AGE: 2 MONTHS. SEXUAL ABUSE OR ASSAULT REPORTED: NO. CONSENSUAL SEXUAL RELATIONS WITH 21YO IN COO.” Before reading about it (the structure is a feature of traditional Korean architecture that marks domestic entryways; the lines are borrowed from border documents about pregnant minors), I found these words, and this work, to be the most arresting of all, more physically disturbing than my motion sickness in the headset. Standing before it, I knew it was a threshold inviting a body, my body, to pass through, and yet the threat of the language made me queasy upon approach. I was spurred to reverse-engineer the text and try to imagine the people from whom this data was extracted. Here, as with the bracelets, Han makes the supremely impersonal feel painfully personal.

Bang Geul Han: Land of Tenderness, installation view. Courtesy The 8th Floor. Photo: Adam Reich. Pictured: Threshold, 2022 (detail). Wood, light pipes, aluminum, custom electronics, custom software.

Bookending a very odd day, that evening I went to a church to try to help asylum seekers fill out applications registering their physical presence in US territory. I listened to harrowing testimony and tried to squeeze their stories into small boxes according to obscure instructions. In shock, I saw my own hand replicating some of the words I’d seen in Han’s LEDs. I was acutely aware again that I was trapped by language not entirely my own, and that abuse of language conceals abuse of bodies. The tedium in the room was palpable, and the work was probably pointless. Might as well shred these documents and weave them into a blanket, I thought while writing. At least it would keep us warm.

Elvia Wilk is a writer living in New York. She is the author of the novel Oval and a book of essays called Death by Landscape. Her work has appeared in publications like frieze, Artforum, Bookforum, the Atlantic, the Nation, Granta, the Paris Review Daily, the Baffler, n+1, the White Review, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is a contributing editor at e-flux Journal.