Elvia Wilk

Elvia Wilk

Chris Kraus’s new novel chronicles the crimes and injustices

of rural impoverishment.

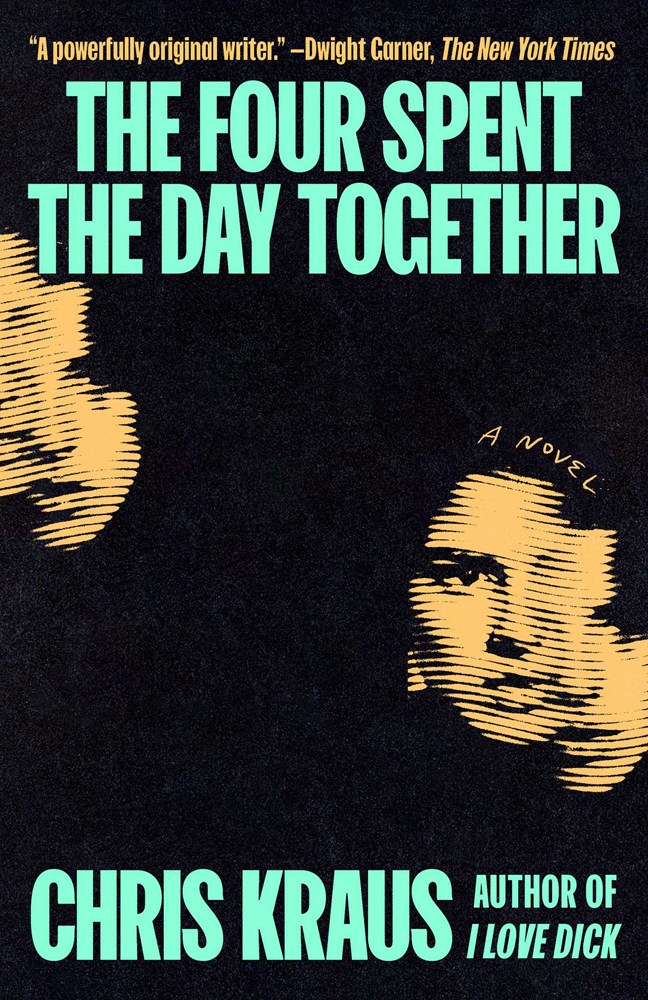

The Four Spent the Day Together, by Chris Kraus,

Scribner, 304 pages, $29

• • •

Most people remember the sex in I Love Dick; I remember the class. Chris Kraus’s legendary 1997 autofiction chronicles her love letters to a man she was obsessed with—a game of desire whose voltage came from real asymmetries of class, capital, and access.

From that view, Kraus’s new book, The Four Spent the Day Together, is another genius twist of the knife rather than a departure from her past works. It’s billed (brilliantly and misleadingly) as a true-crime novel, but by the time you get to the shocking crime with which it culminates, countless others of varying scales have piled up. Most overt is the sweeping nationwide crime of rural impoverishment; then there are the endless tiny, daily injustices that result. If genre-faithful true crime seeks sense in motive, Kraus is seeking those senseless systems that both produce violence and strip it of meaning.

As is often the case in Kraus’s fiction, the protagonist of The Four is an alter ego. In Torpor (2006), she was Sylvie; in Summer of Hate (2012), she was Catt Dunlop; here, she’s Catt Greene. The book’s first section novelizes Catt’s 1960s childhood, focusing on her mother, who escapes an airless parochial life to marry Catt’s father, an autodidact determined to work in publishing. Driven by a fantasy of upward mobility, the family of four moves from the Bronx to the Connecticut town of Milford, landing in a purgatorial class position between the working poor and the beachfront elite.

Catt’s dad takes her on as his intellectual protégé. (Was a “book about Gothic and Romanesque arches too advanced for a four-year-old girl? He didn’t think so.”) But by adolescence, a bullied and disaffected Catt is huffing glue and hitchhiking to biker dives and Black Panther rallies. Her mother, confined at home and strapped for cash and company, is “lonely, so bored and depressed.” Their American Dream dashed, her parents abruptly announce they’re moving to New Zealand for a fresh start.

Cut to some forty years later. The next section, “Balsam,” feels like classic Kraus third-person autofiction: hypnotic, harrowing, intimate. Echoing her father’s fated love affair with the promise of Milford, middle-aged Catt happens upon a vacant lakeside cottage in the rural Minnesota town of Balsam and is “sick with desire” to live there. The rest of the book circles around this Minnesotan region, the Iron Range.

The public events in Catt’s life map closely onto the author’s. We watch Catt write the Kathy Acker biography that Kraus published in 2017, we tag along on a tour for the I Love Dick reissue, which rebranded her as an It Girl twenty years after its release, and we visit the production set where it’s adapted for TV.

But what happens in private between Catt and her then-husband, Paul, is the emotional core of the novel. Paul was two years sober when they met in Albuquerque in 2005, and three years later they moved part-time to Minnesota so he could get a degree in addiction studies. Over the years of their relationship, he works as a counselor in various treatment centers and relapses repeatedly into drinking and drugs.

Balsam is gorgeous. The cottage is Catt and Paul’s container for their dream of tranquil domestic life: artistically generative for her and sober for him. But they’re often apart for work, and Paul is often apart from himself. In good phases, they ski and hike; in bad phases, Paul hides vodka bottles behind the clothes dryer and explodes in rage. “Alcohol is an evil spirit,” Paul says, a spirit that wants to “destroy everything and everyone around him.”

Like their relationship, the idyllic landscape is scarred. The postindustrial vacuum left by the mining boom has yielded a drug epidemic—young people’s futures foreclosed, inner lives evacuated. I think of another true-but-not-traditional crime book, Jonathan Lethem’s 2023 Brooklyn Crime Novel, where the crimes are real-estate speculation and gentrification as much as any person-on-person attack.

A landlord herself, Kraus has been accused of cashing in on gentrification. She details her public hazing as a “slumlord” in part two. After Catt watches two art/academic icons be pilloried (Knight Landesman is cloaked as “Galen Stein,” Avital Ronell remains Avital Ronell), a Twitterstorm descends on Catt the Capitalist. “Catt Greene, people said, had been canceled.”

Kraus has never been secretive about how she earns money. In Summer of Hate, Catt Dunlop finds a way to support herself and also “to do some small good in the world, rehabbing apartments in low-income neighborhoods to make them as nice as they can possibly be.” In The Four, Catt Greene aims to “make a small profit without raising rents or displacing people.”

In her incredible 2000 book Aliens and Anorexia, Kraus, speaking of another woman, inadvertently describes herself: “She was a genius tossed upon a world with no place for working class girl geniuses.” Kraus did eventually make a place for herself—through ambition, “charm,” brilliance, and yes, real estate. When the online hate crescendos, Catt “wondered if it was the proximity to poverty she allowed herself that enraged them.” But she doesn’t turn contrite or reactionary. She takes the opportunity, yet again, to steer away from purity politics and get deeper into the muck we’re all mired in.

• • •

In 2019, Catt reads about a murder in the nearby town of Harding. A seventeen-year-old, an eighteen-year-old, and a twenty-year-old took thirty-three-year-old Brandon Halbach into the woods and shot him. Before the killing, the newspaper reports, “the four spent the day together.” The oddness of this line impels Catt to investigate. Her research forms the book’s third section.

Catt sets up shop in Harding, interviewing locals and law enforcement, and eventually exchanges letters with Brittney, the only woman involved, who planted the idea of murdering “Brandon something” after accusing him of assault. But the story is bleak and revelations scarce. The murderers were high, or trying to get high, and inarticulate. Anyone who’s battled addiction knows there’s no sense to it, but there is a grim logic. Counting drinks. Bargaining. This murder proceeds in the way that Paul describes the inevitability he feels: “Every relapse began with a plan, and once the plan entered his mind he was helpless to shake it.”

This section is jumbled; characters ramble in and out, as their family members enter and exit their lives or OD and vanish. Narrative breaks down, cars break down, social services break down. The further Catt gets into the region’s history, the more pointless violence she finds. Paul, working at one point as a counselor in regional juvenile detention, calls what he sees “a perpetual stream of dysfunction and misery.” A homicide detective tells Catt that in eighteen years on the job, he can’t remember a murder case that didn’t involve meth.

In the opening scene of the book, four-year-old Catt discovers wordplay when her father makes a small joke—“an ice toy” becomes “a nice toy”—and “she smiled, the elliptical meanings of words rolling around in their mouths like hard candy.” Catt may not be set up for money, but she’ll have a life of the mind.

The kids of Balsam are not rolling the candy of language in their mouths. Kraus ends with an appendix of messages the murderers exchanged leading up to the crime. Their chats are largely like this:

JD: hi sexy

BM: sup

JD: wyd

BM: chilling

JD: fun

These texts are not rich text. They’re poor text. They don’t lend themselves to the illuminating, associative analysis Kraus is so gifted at. She has to let them speak—or not speak—for themselves. In I Love Dick, Kraus asked: “Is poverty the absence of association?” She meant association in terms of social relations, but also in terms of language. The drugged murderers are disassociated in every sense. What a fucking tragedy. What a crime.

Elvia Wilk is a writer living in New York. Her third book, a novel, will be published in 2026.