Hanif Abdurraqib

Hanif Abdurraqib

In a previously unpublished book, Zora Neale Hurston profiles a survivor of the last US slave ship.

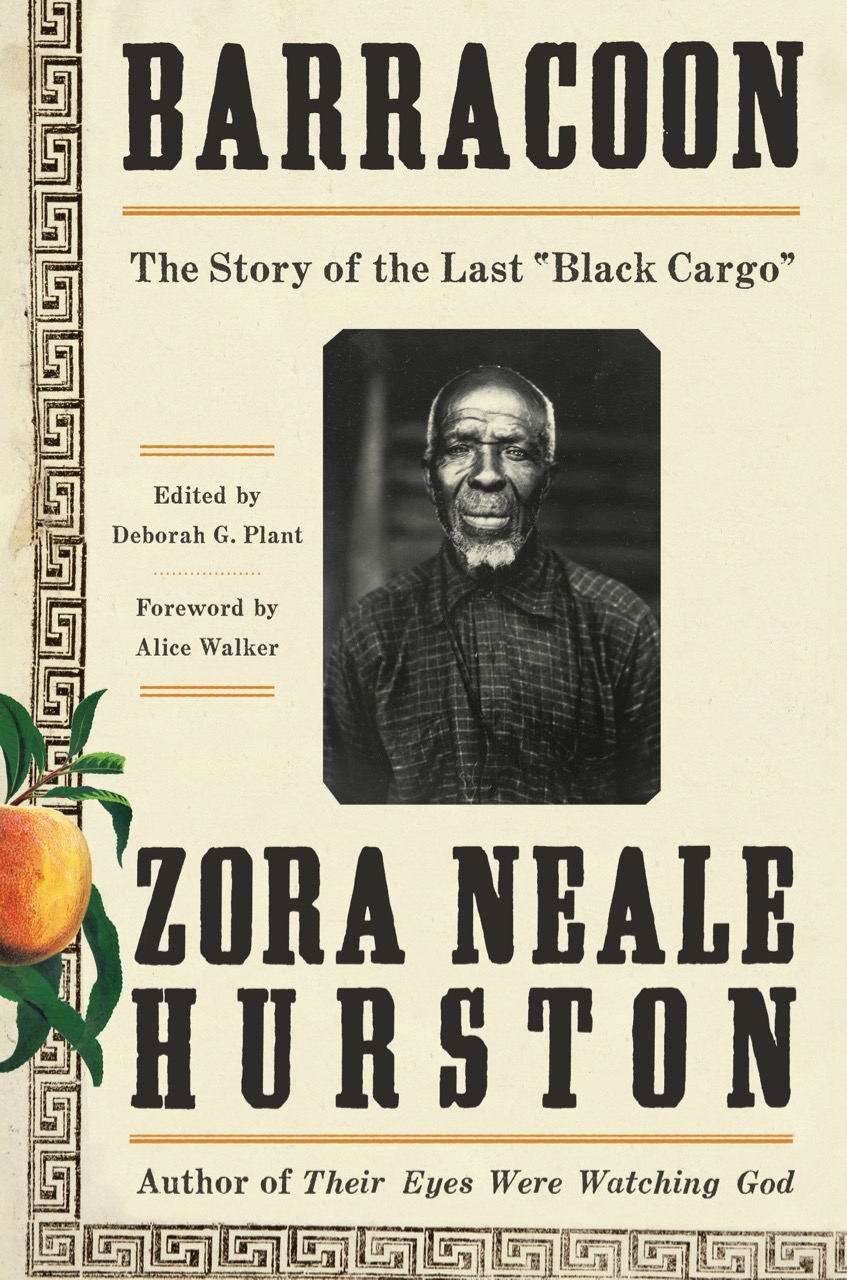

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” by Zora Neale Hurston, Amistad, 168 pages, $24.99

• • •

In 1927, Zora Neale Hurston was a young writer, ten years away from releasing what would become her landmark work—1937’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. She had published a few poetry collections and written a screenplay, but had yet to make the mark she would eventually leave on the literary world. She was then an anthropologist, and her eager curiosity carried her to a town called Plateau, Alabama.

Plateau was a community founded by Cudjo Kassula Lewis and other former slaves, three miles from Mobile. Cudjo was now eighty-six years old and nearing the end of his life. He was the last African survivor of the Clotilda, the final US slave ship to bring captives from Africa to the States; it had arrived in the summer of 1859 or 1860, carrying approximately 110 slaves. Cudjo had the rare opportunity to act as a living archive for writers and historians. He could tell richly layered stories about the raids on his West African village, and the traumatizing cross-ocean travel.

Hurston went to Plateau a few times: twice in 1927, and then again in 1931, when she spent over three months there, talking in depth with Cudjo about the details of his life. The result of that work, penned in 1931 and only now being published, is Barracoon. (The title comes from the name for the enclosure in which black slaves were kept for transport.) The book is written partially from Cudjo’s perspective, from the hand of Hurston, who, although using his words as an account, is able to put a prose spin on the retelling. The text is not long—once one gets past the prefaces and the intros, the story itself is only ninety-five pages. Because she was working as an anthropologist, Barracoon presents itself as something of a scientific document, even though Hurston writes in the preface that it makes no attempt to be one. In that intro, she expands on her thoughts about the slave trade and what drew her to flesh out Cudjo’s story. The idea is that seeing America through the lens of the slave trade—despite its broad stain on the country’s history—is best done from the point of view of a single person who had their life forever altered by it. Barracoon, in many ways, pursues the slavery narrative in the same manner as the book and film 12 Years a Slave: it tracks slavery’s violence and aftermath through the words, memories, and history of a single person who survived it.

Holding the book and reading it now, Barracoon seems ahead of its time, largely due to how it makes the story of slavery both intimate and viscerally visual, as Roots did most notably several decades after this manuscript was created. (The book’s visual, film-like nature also brings to mind the slave narratives—both true and rewritten—we’ve seen pop up in movies recently, to both acclaim and criticism: The Birth of a Nation, Django Unchained, the aforementioned 12 Years a Slave.) Part of this visual aspect is the work of Hurston, who richly describes the touchable moments meeting and interacting with Cudjo—from bringing peaches to his doorstep, to the sugarcane growing in his yard.

But even richer are the times when Cudjo is the sole narrator. This happens without notice, the “I” shifting abruptly from Hurston’s recounting to Cudjo’s first-person story. This is jarring, but also delightful in how it surprises each time, his evocative narration adding to the visual aspect of the book. Because Cudjo was already nineteen years old when captured, his memories of the event and subsequent journey are particularly vivid. Most notably, he recalls decapitated heads hanging from the belts of soldiers who stole him from his land. He describes the pain of watching the fellow slaves he’d traveled with being sold away to other plantations, the tearing apart of this forced, and then chosen family.

Hurston writes Cudjo’s voice as it was spoken out loud to her. Her strength in articulating dialogue is something that shines in her later work, but it is seen brilliantly here, despite this being language transferred to her from a person in front of her. Cudjo’s dialect is singular and unique, and the greatest thing Hurston does in the book is honor the sonic qualities of it. Not sacrificing “dey” for “they” or “lookee lak” for “looks like.” Cudjo’s story is one of an aging man piecing together several disparate horrors, and Hurston lets his language exist, trusting readers to find their way through it. Cudjo is at times funny, heartbreaking, sharp, and metaphorical. At the end of one passage, after describing witnessing the dissolution of a family, he says:

“Our grief so heavy look lak we can staind in it.”

It is best to imagine Barracoon as an exchange between two people trying to reckon with history: Hurston, as a curious writer and anthropologist and black woman in America, coming to grips with the horrors of slavery while so many of those horrors were still echoing on the landscapes she lived. And Cudjo, trying to tell his story while he was still alive to do it—one of the last people who could get those stories out of himself, before history worked overtime to erase them. The thing about an immediate and urgent archival project like Barracoon is that it is really doing a service to the person telling the story above all, and then it serves whatever witnesses of that story there are. If we do not tell someone our histories, our histories might be told for us, by people who don’t always have our best interests in mind.

Barracoon is a difficult read, harsh and brutal at times, with just enough levity to help push a reader through. Cudjo ends his story as a full human, beyond the terrors he endured. Hurston’s book is about a person surviving, despite every attempt made for him not to. It seems triumphant, I’m sure. Until you remember what you’re celebrating the triumph over.

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic from Columbus, Ohio. His first collection of poems, The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, was released in 2016 and was nominated for the Hurston-Wright Legacy Award. His first collection of essays, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, was released in fall 2017 by Two Dollar Radio.