Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Curator Lynne Cooke challenges notions of insider and outsider art.

Outliers and American Vanguard Art, installation view. Image courtesy the National Gallery of Art.

Outliers and American Vanguard Art, National Gallery of Art, Sixth Street & Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC, through May 13, 2018

• • •

Perhaps it is best to start a conversation about Outliers and American Vanguard Art—a sprawling, ambitious exhibition curated by Lynne Cooke at the National Gallery of Art—by specifying what it isn’t. First, it is not a show of “outsider art,” contrary to first appearances, though many of the eighty-plus artists on view have been saddled with that term or one of its many cognates (folk, primitive, vernacular, naive, visionary, unschooled, self-taught, etc.). Second, it is not an exhibition about the influence of outsider artists on the American vanguard, despite the fact that vanguard and outsider works are placed in dialogue throughout and the niggling “and” in the title of the show.

Rather, as one would expect given Cooke’s brilliant curatorial career at the Museo Reina Sofia and the Dia Art Foundation, and the years of research that went into the show, Outliers seems to propose something far subtler, even radical: a reading of three critical periods in the past century of American art during which the modernist dialectic of outsider and insider broke down to a point of meaninglessness. This collapse only becomes legible when objects typically held on either side of the insider/outsider divide are brought together, as they are in Cooke’s show.

Marsden Hartley, Adelard the Drowned, Master of the “Phantom,” c. 1938–39. Oil on board, 28 × 22 inches.

What then becomes apparent is the formation of a third term: “outliers”—eccentric, unruly creators whose work, if we are truly to make sense of it, must be seen in the context of a much broader accounting of American art than modernist approaches usually allow. The new moniker of outlier artist is capacious enough to accommodate such well-known figures as Jacob Lawrence, Marsden Hartley, Zoe Leonard, and Kara Walker, as well as many whose names are much less familiar in the annals of art history.

Following her curatorial premise, Cooke has divided the exhibition into three sections, during which social conditions conspired to allow outlier artists to flourish: the years leading up to, and spilling into, the Second World War when populism and nativist ideals fueled an interest in folk art and vernacular traditions (c. 1924–43); the era of civil rights, feminist, antiwar, and gay rights struggles, when even esoteric art historical categories were recognized to be sites of ideological struggle (c. 1968–92); and a contemporary period starting in 1998 that saw “the integration of the works of schooled and unschooled artists together without hierarchical distinction on a level playing field,” the curator claims.

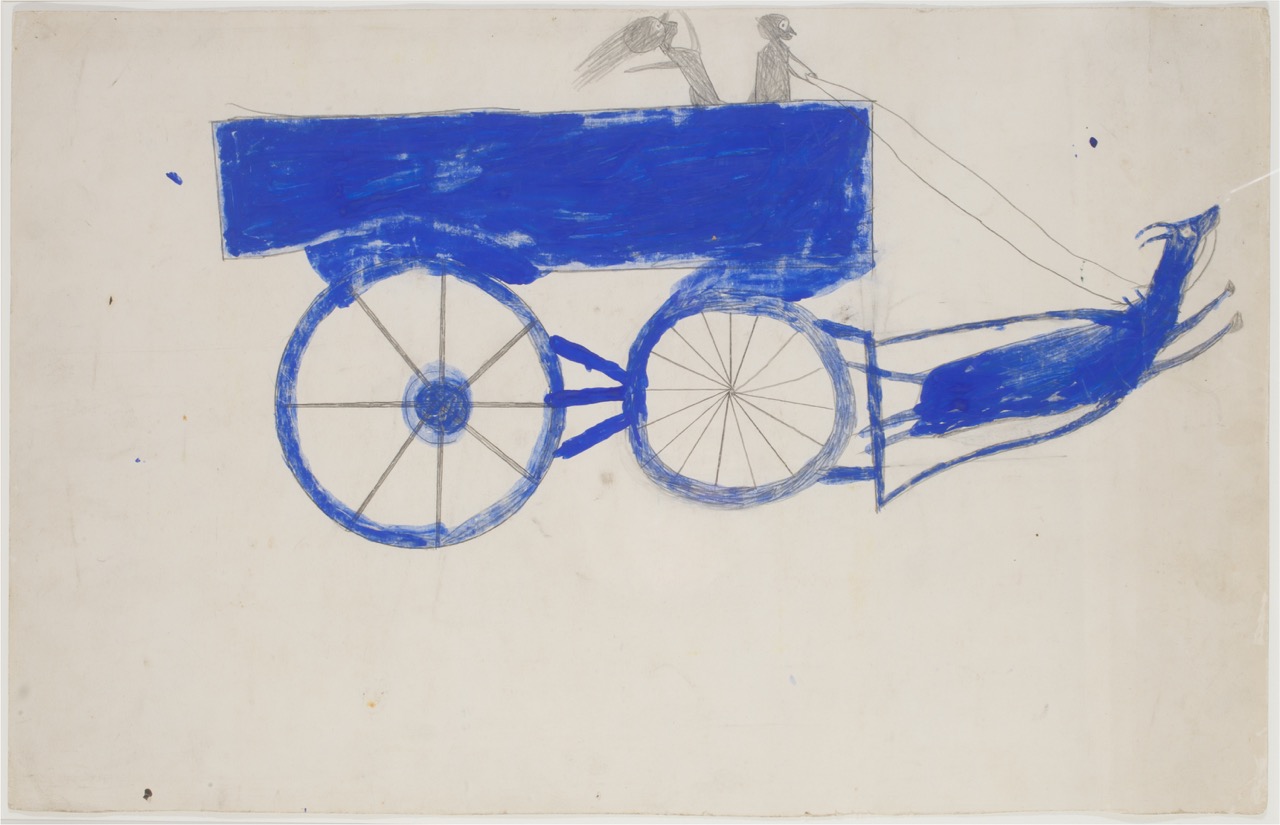

Bill Traylor, Runaway Goat Cart, c. 1939–42. Opaque watercolor and graphite on cream card, 21 ¼ × 29 ¼ inches.

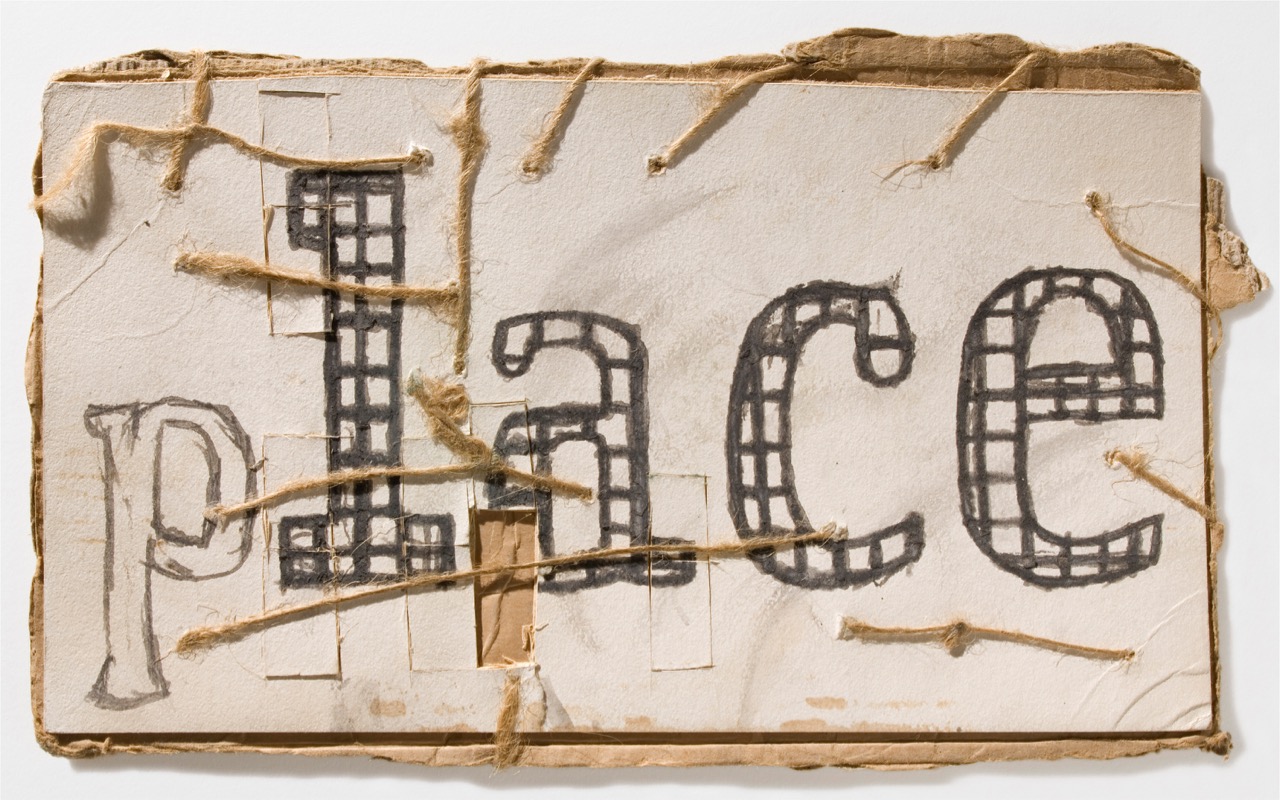

The label of “outsider” has generally been attached to artists on the basis of their distance, whether self-imposed or the product of structural exclusions, from the institutional frameworks that art history uses to confer “insider” status (such as schooling or participation in the right kind of art exhibitions); these frameworks are, in turn, often determined by the artist’s race, gender, class, geographical location, and so on. As such, directing one’s attention to moments when an outlier category emerged opens a space for recognizing so many makers, ideas, and practices that modernism has long resisted, or only accepted begrudgingly: craft processes, regional idioms, traditional “women’s work” such as textile arts and beading, the work of black and Chicano artists long ignored by mainstream art history, the role of religion and spirituality in American visual culture, the artistic value of utilitarian objects, the unironic, artists making installations in their backyards, and so on. But Cooke’s goal is not, it seems to me, simply to get us to recognize these “outsider” works as proper art—but to signal another way through the American visual landscape of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It allows for a retelling of the story of American art that includes Bill Traylor’s vivid, sweetly terrifying watercolor and graphite picture, Runaway Goat Cart (c. 1939–42); James Castle’s formally complex and materially bizarre images made of soot and saliva on found paper, rivaling any Van Gogh drawing; or Sister Gertrude Morgan’s touchingly funny, spiritual, and visionary tempera, pen, and graphite confections, including Jesus is my air Plane (c. 1970). These are positioned not just as eclectic one-offs, but as part of a larger logic of cultural production.

James Castle, Untitled (place/lace), no date. Found paper, soot and saliva, string, 9 ½ × 16 ⅛ inches.

The exhibition makes its point most forcefully in the first room and in one of the last. One enters through a gallery containing works by Jessica Stockholder, Judith Scott, Nancy Shaver, and Rosie Lee Tompkins, which complicates notions of assemblage—collapsing artificial distinctions between modernist formalism and vernacular accretion, between collage and patchwork, between sculpture and craftwork, and so on. In the later room, we see works by Alan Shields (a near-square frame covered in a grid of canvas belting embellished with acrylic, thread, and beads); Howardena Pindell (a support composed of hand-sewn canvas squares covered with a complex, delicately colored array of paper discs, sequins, glitter, and perfume); Mary Heilmann (an abstract oil on canvas); Annie Mae Young, Mary Lee Bendolph, and Rosie Lee Tompkins (quilts, made of a variety of traditional and not-so-traditional fabrics and patterns); and Al Loving (a mixed-media work that could be taken for a deconstructed quilt or a distant cousin of a Rauschenberg combine). In both galleries, the question of insider/outsider is moot—I was hard-pressed to figure out who was supposed to fall into which category. More importantly, in both rooms, the strange beauty of the assembled works was allowed to reveal itself as a function of shared DNA, not mere surface resemblance, like long-lost siblings reunited across time and space.

Outliers and American Vanguard Art, installation view. Image courtesy the National Gallery of Art.

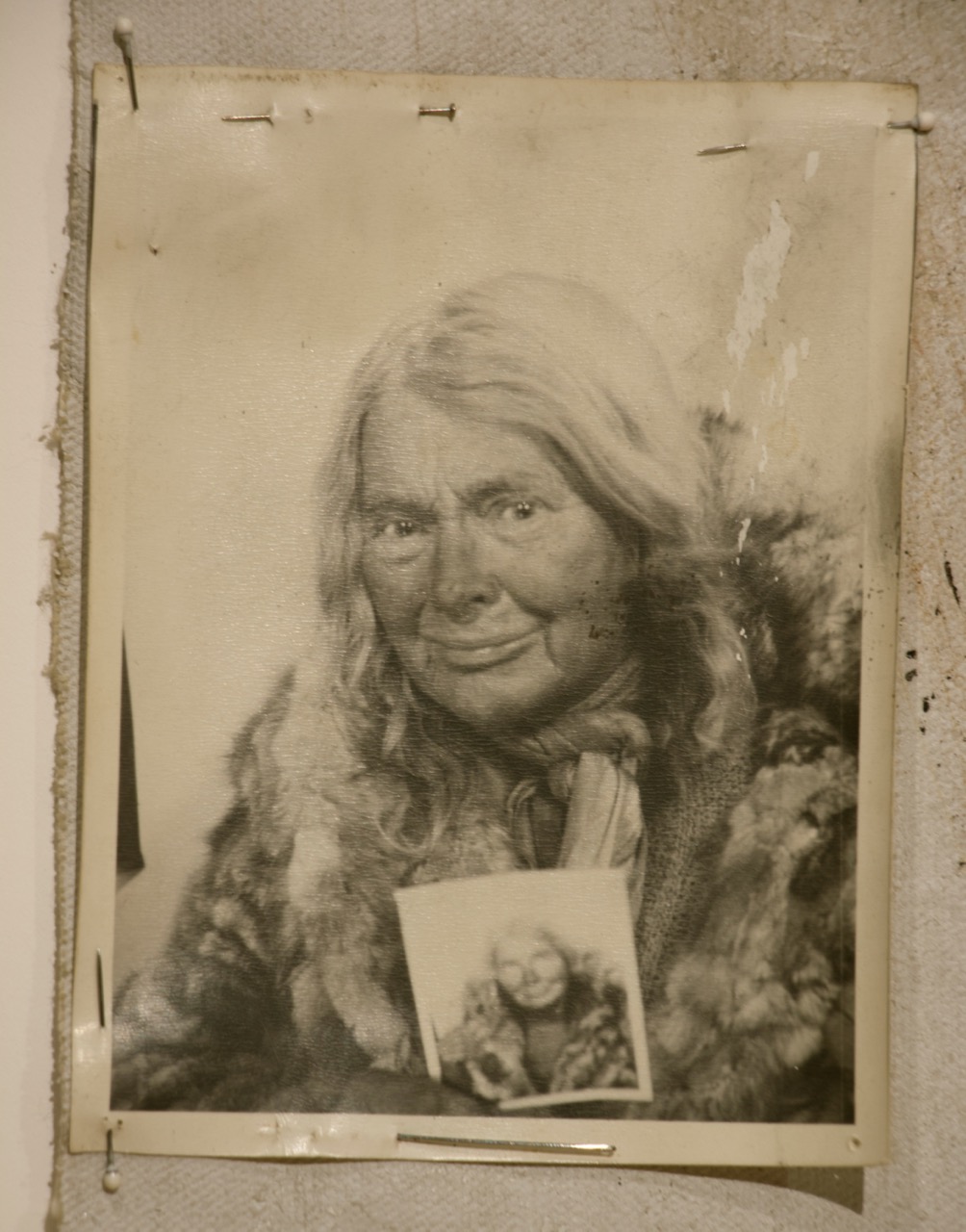

There are points in the show where the grouping of works performs not just a vital illumination of historical and notional affinities, but a potential rewriting of art history itself, in ways that often threaten to demote sacred cows as much as elevate underappreciated makers. Such is the case in a grouping of photographic works that explore feminine masquerade. How tepid Cindy Sherman’s film stills look next to the whimsical self-portraits of Lee Godie, a Chicago woman who became a transient and an artist later in life, and who took photos of herself performing the roles of posh ladies and French ingenues in the photo booth of the Greyhound bus depot, sometimes pasting them onto canvases covered with touchingly naive drawings. Sherman’s noir sensibility and postmodern distance contrasts, not entirely to her benefit, with the unmediated playfulness and sheer resourcefulness of Godie’s work—and, as a consequence, might spur us to reconsider the elitism inherent in our usual definitions of conceptual art.

Lee Godie, Prince Charming, c. 1975–80. Paint, ink, and gelatin silver print on canvas image, 25 ¼ × 15 ¼ inches.

That is not to say that the exhibition is faultless, by any means. One of the biggest blind spots, for me, was the almost total absence of American Indian artists—they are evoked as primitivizing influences on artists in the show, but not imagined at all in the landscape of outlier art that the exhibition maps. (The only exception is Joseph E. Yoakum, maker of schematic and symbolic landscape drawings of the American West, who was of Cherokee and black ancestry.) Formally and conceptually, the work of figures ranging from Edgar Heap of Birds to Jeffrey Gibson would quite easily have found a home among the objects on display in Outliers; their absence underlines the continuing exclusion of contemporary indigenous practices from our definitions of “American art,” a sad failure in an undertaking that otherwise upends hoary museological categories. Given that Outliers is a show that will launch many, many exhibitions in its wake, as curators grapple with the complexity of the historical narratives it proposes, I can only hope that omissions like these will soon be rectified.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her new book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, will be published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.