Rumaan Alam

Rumaan Alam

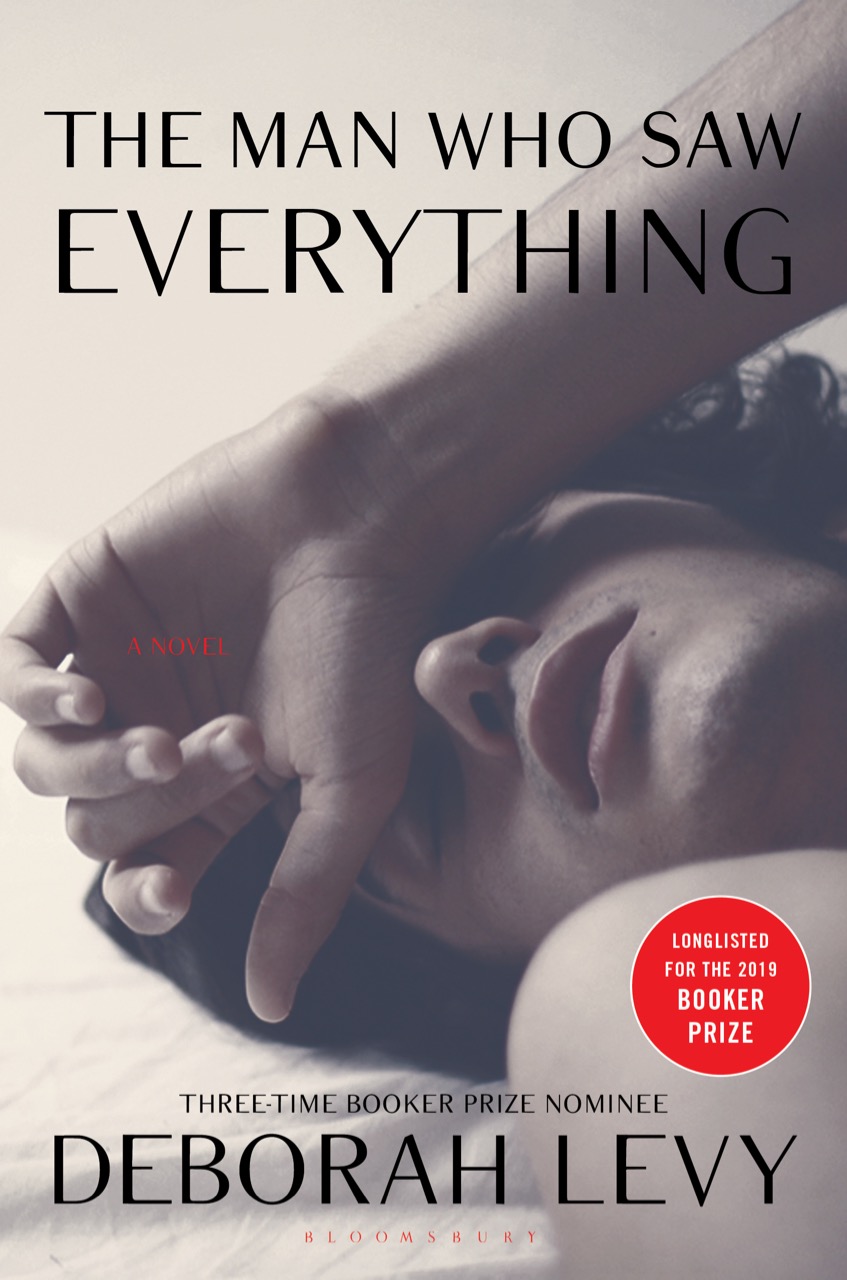

In Deborah Levy’s new novel, East Berlin meets Abbey Road.

The Man Who Saw Everything, by Deborah Levy, Bloomsbury,

199 pages, $26

• • •

There’s a throwaway line in The Man Who Saw Everything, Deborah Levy’s eighth novel, that caught my attention: “I wasn’t sure what was going on or why he was laughing.” The context is immaterial; I cite it because it strikes me as a précis of Levy’s project in this book (and her earlier novels, and her two lovely volumes of memoir): confusion leavened with humor.

Everything’s titular man is Saul Adler. The story opens in London in 1988. Adler is taking the Abbey Road pedestrian crossing made famous by the Fab Four when he’s grazed by a passing car. Fear not: he’s fine. Saul’s girlfriend, Jennifer, shows up; she’s a photographer, and they’ve arranged for her to take a picture of him in that very crossing, an homage to the Beatles.

Saul is a historian, bound for East Berlin to complete some research (one imagines that Levy chose his subject, “cultural opposition to the rise of fascism in the 1930s,” quite deliberately) and the photo will be a present for Luna, a passionate Beatles fan, the sister of his host and translator, Walter. Just before Saul leaves for Germany, Jennifer breaks it off with him. We follow along behind the wall, where Saul falls in love with first Walter and then Luna.

This all sounds like the synopsis of a big fat book, but Everything clocks in under two hundred pages. As ever, the author’s pacing is nearer the movement of thought than a received idea of the structure of a novel. Levy sometimes dispenses with scene setting or context (one chapter is simply three sentences). She breaks rules (the book is told in the third person, but opens with a paragraph in the first person). She’s sometimes plainspoken, but in other moments indulges in linguistic flights of fancy. Levy is confident, both in her abilities and her reader’s intelligence. It’s bracing, almost shocking.

The proceedings in this book mostly seem real, or realist, but then, sometimes, they don’t. Upon hearing that Luna wants to escape the country, Saul seems to know the future: “In September 1989, the Hungarian government will open the border for East German refugees wanting to flee to the West. Then the tide of people will be unstoppable. By November 1989, the borders will be open and within a year your two Germanys will become one.” He is, as the title promises, a man who sees everything.

Earlier, first meeting Luna, Saul tells us, “I could see myself smiling in both her eyes, as if I had become a double self, which in a sense was right.” This becomes literally the case when the novel leaps to 2016. Saul Adler is back at the Abbey Road crossing when he’s hit by a car. He wakes in a hospital, and the logic of the book is challenged. Saul believes he is twenty-eight years old but discovers he’s fifty-six. His father is not dead, as we’d been told, but sitting at his bedside. Jennifer remains his ex-girlfriend, but she’s all grown-up, now a famous photographer. His doctor looks uncannily like a man he knew in East Berlin.

The obvious question—what’s going on?—doesn’t interest Levy. It’s immaterial whether the section set in 1988 is the fever dream of the man struck by a car in 2016, or his actual past, or some alternate reality. For me, metafictional ploys usually grate. But Levy is such a good writer, such a weird writer, that she more than pulls off what would feel, in lesser hands, like a gimmick. It’s never clear how to reconcile the book’s first half with its latter, and this ends up being what makes the book so charming.

Even Saul is at a loss. “Perhaps I was history itself, flailing around in a number of directions, sometimes all of them at the same time.” On screen, the multiverse—in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar or the animated feature Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse—is a popular gambit (maybe since it’s the ideal solution for a writer who has painted herself into a corner). Everything is possible, whether it’s an astronaut communicating with his past self or several versions of one superhero coexisting.

In books—though they’re quite different works, I thought of Helen Phillips’s wonderful recent novel The Need and Kazuo Ishiguro’s superb The Unconsoled—this is a strategy that destabilizes the reader. If you can’t trust authorial, well, authority, then what are you supposed to do? Still, I wouldn’t classify Levy’s book (or Ishiguro’s, or Phillips’s) as metafiction. The aim isn’t to confound the reader in service of some point about literature itself. In Levy’s book, the slippage between one reality and the next suggests that reality itself is richer than she can convey. She’s not admitting failure, but marveling at possibility.

Everything isn’t a novel about novels. It’s a love story—young Saul has his heart broken by Jennifer, then breaks the hearts of both Walter and Luna—with a healthy dose of lust story, too. It’s a story interested in collapsing binaries: the idealism of youth and the inevitable disappointments of age (older Saul has his heart broken in a way I found truly affecting), art (particularly photography; there’s an epigraph by Sontag) and commerce, politics and history.

Levy repeats phrases or images or motifs (the notion of haunting, the jaguar the animal and the Jaguar the car, the Beatles, bodies swimming through water, a pearl necklace at the throat) often enough that the reader wants them to mean something. And perhaps they do! You’re so busy trying to make meaning of the small stuff—isn’t that what reading is?—that you’re less concerned whether the book fits together tidily, as most of us expect novels to.

I cannot claim to have a cogent theory of what is happening in The Man Who Saw Everything, and I would be skeptical of any reader who did. It’s a strange book, and Levy concludes it on a note that’s downright baffling—yet somehow quite apt. Many novels fray or indeed unravel altogether at their ends. Levy gleefully tugs at hers, pulling it apart, but somehow it still holds.

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novels Rich and Pretty and That Kind of Mother; his third novel will be published in 2020.