Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

An incandescent force field: the electronic composer’s

Chry-Ptus is reissued.

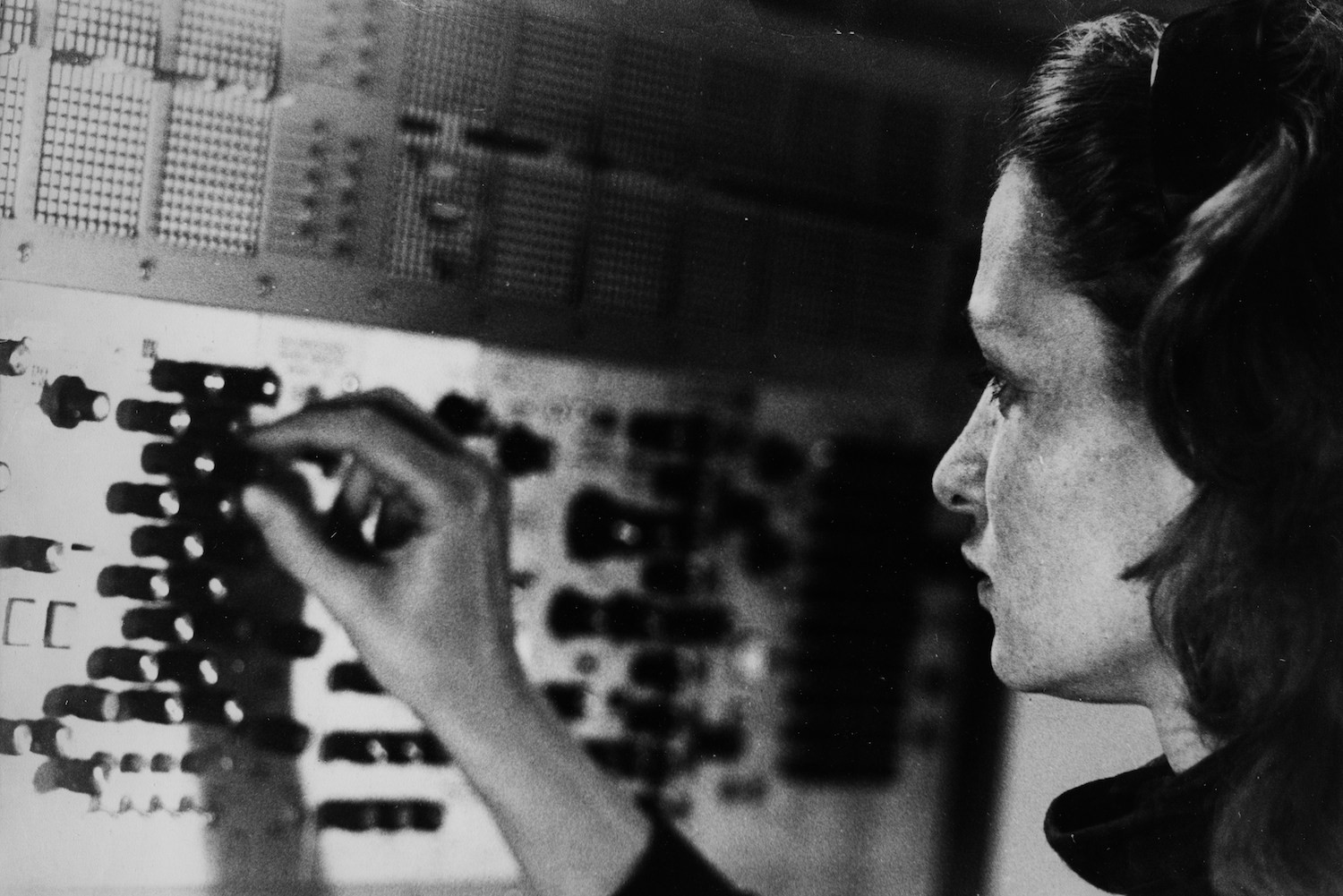

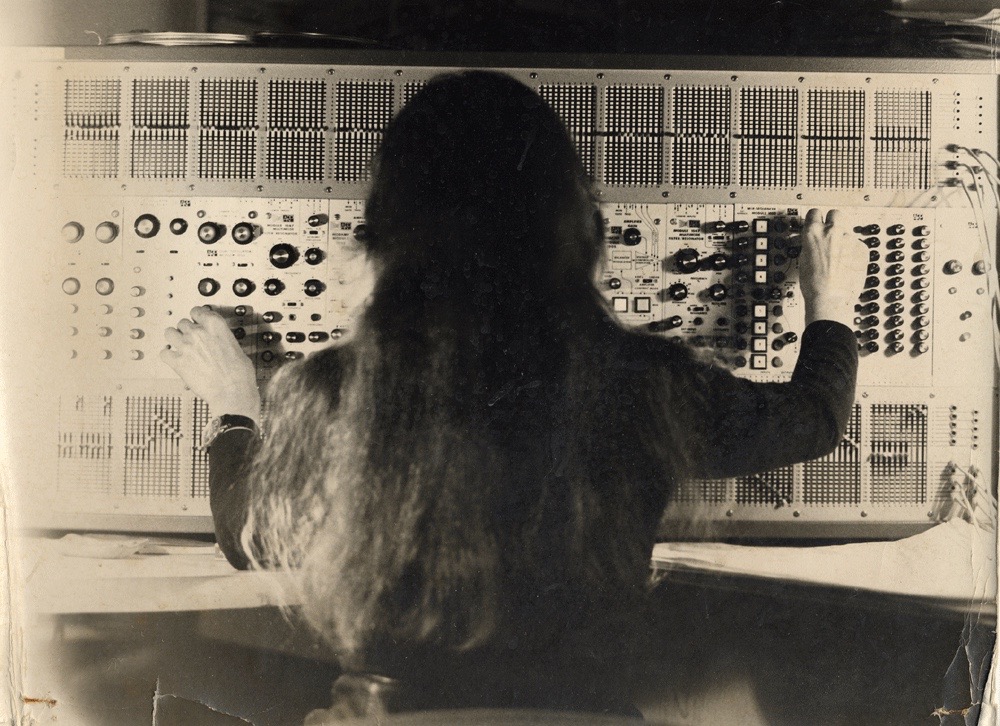

Éliane Radigue in her studio, Paris, ca. 1970s. Photo: Yves Arman.

Chry-Ptus, by Éliane Radigue, Important Records (reissue)

• • •

The long arc of Éliane Radigue’s career parallels the modern history of electronic music. She is now eighty-seven years old, and her work—which spans six decades—still sounds completely singular. For many years, the legendary composer was an outlier in her home country of France, where the intricate sample collages of musique concrète, beginning in 1948, formed the modern foundations of electronic music. Musique concrète, usually associated with tape editing, was obsessively designed and maddeningly labor-intensive. Radigue’s approach to making electronic music was hard work, too, but it was less about controlling sounds and more about surrendering to them.

Early on in her career, she assisted Pierre Henry, one of musique concrète’s primary exponents, but grew exhausted with the long hours and incessant demands, soon breaking out on her own. She had developed her own distinct aesthetic. “When I was working as an assistant to Pierre Henry in the early ’60s he gave me a pile of tape, and asked me to make a montage using only the attacks of the sounds,” she recalled in a 2011 interview with Paul Schütze in frieze. “So you had a ‘ta-ta-ta-ta’ sound . . . But I preferred what was left after the attack—if you cut the sound of a bell just after the attack, you have this beautiful game of the harmonic, and the ear is not ‘attacked’ by it.”

Éliane Radigue.

In the 1960s she began experimenting with feedback, creating several works that felt jagged and wild. At the start of the 1970s she went deep into analog synthesis, composing the slow, meditative ambient electronic explorations she is best known for, and embarked on an intensive personal study of Tibetan Buddhism. From 2005 on, she has delved into acoustic music, working on several collaborations. Over the past two decades her legacy has grown massively, inspiring legions of younger fans. A comprehensive schedule of reissues continues apace, including a fourteen-CD retrospective box set, and new vinyl editions of her early work—most recently Chry-Ptus.

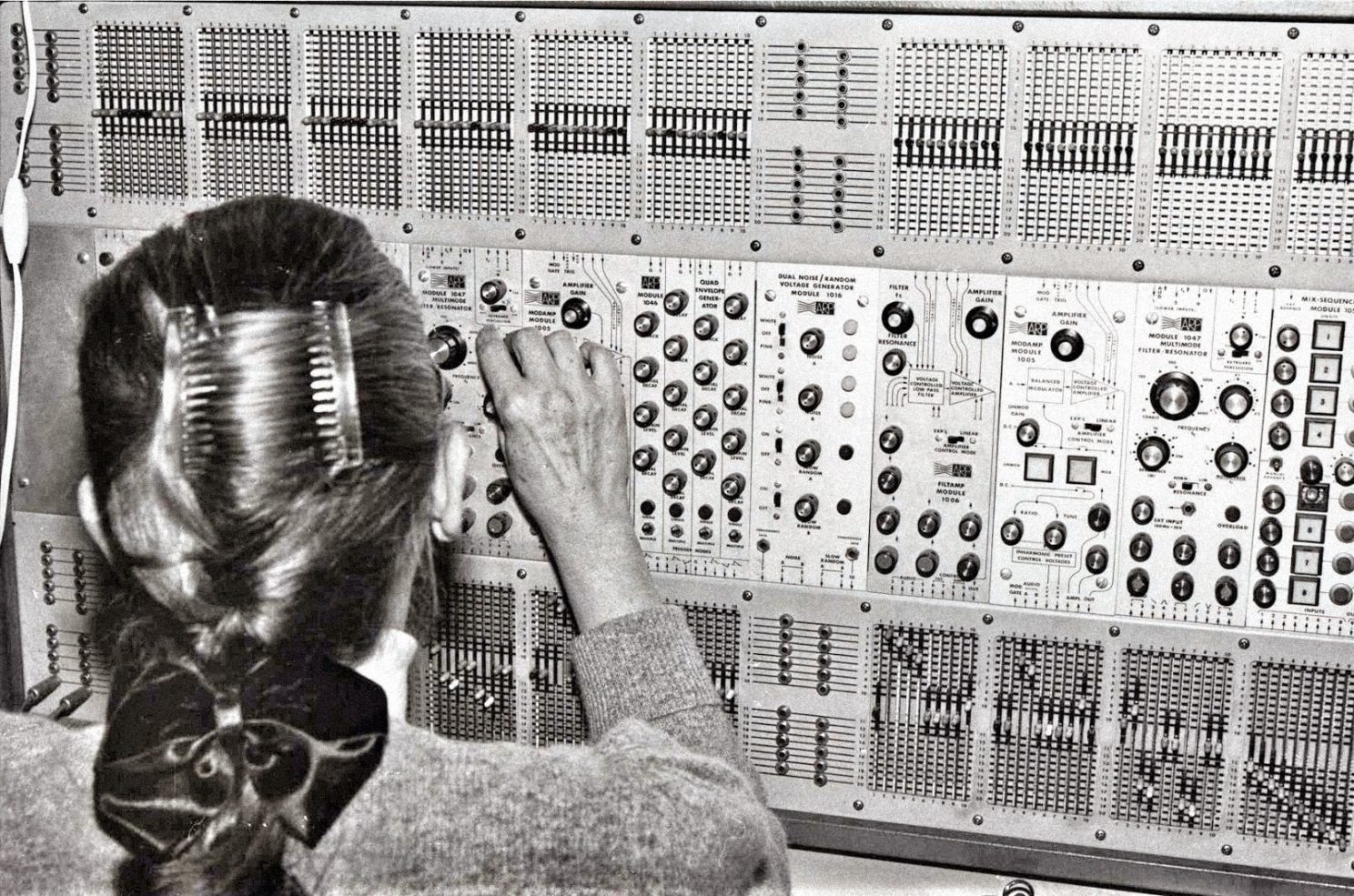

The original 1971 version of Chry-Ptus (featured on this release along with newer iterations from 2001 and 2006) was made in New York using the Buchla 100 modular system, at an NYU music lab famously established by Morton Subotnick. The lab became a de facto downtown center for electronic experiments, nurturing budding composers like Radigue, Laurie Spiegel, and Rhys Chatham, separate from the more academic goals of the famed Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center uptown. By this time, Radigue had spent several years exploring feedback, in experiments using tape machines and other devices. Those pieces aren’t so easy to listen to: the abrasive high frequencies feel somewhat akin to being swarmed by bees. Chry-Ptus is another one of Radigue’s challenging experiments, with all the rough edges intact.

It marks a turning point in Radigue’s career—the bridge between her chaotic feedback works and her luminous, reflective synthesizer material. It is her first piece for synthesizer, before her long relationship with the ARP 2500 synthesizer began. (Many of her pieces beginning in the 1970s were made with the ARP 2500, the analog behemoth she acquired in 1971 that became a trusted friend.) Chry-Ptus has an odd, brisk pulse that almost sounds like a washing machine running in a distant room. This arises from an acoustic phenomenon called beating—caused by interference patterns that form between sounds of slightly different frequencies.

Éliane Radigue in her studio in Paris, 1971. Photo: Yves Arman.

“I remember that when I worked on the Buchla at NYU for Chry-Ptus there were those sounds that I got by feedback, which I tried to find again with the synthesizer,” she recalled in an interview with Emmanuel Holterbach. “Beatings, pulsations, sustained sounds that evolved by beats, a kind of transposition of the re-injection procedure. It’s just that with the Buchla you could control things much more rigorously and it was I myself who made them move. At the same time I also kept the system of two tapes, which could play with a different synchronization. I kept that principle of mobility. It is improvising by itself all the time. In some way it is improvising itself.”

Chry-Ptus has two lines, both composed on the Buchla. These two tape recordings could be started at slightly different times, so that each time the piece is performed, it becomes something subtly new. At a concert in New York in 1971, she presented three variations.

The piece rewards patience, slowly revealing itself the more times you listen to it. There is a chirp that sounds like crickets over a deep, ominous undertow. (The late artist Paul Jenkins, who painted the colorful cover art for the release, wrote a poem comparing Chry-Ptus to “fluttering moths with panic, just before dying.”) The timbres stay the same, but small sonic fragments emerge that are reminiscent of noises from everyday life—a refrigerator fan, raindrops, an alarm, static, the busy signal on a land line. As you continue to listen, all the little sounds seem to coalesce into something more cosmic. Soon the music feels like a roiling mass of energy, an incandescent force field. Clocking in at over twenty minutes, with a prolonged fade-out at the end, it is an overpowering experience.

Éliane Radigue.

Radigue’s compositions are long and slow-moving. They are not static, but develop and change in subtle ways—so that, she says, you can hear the richness of the harmonics and shifting overtones. Like other ambient musicians, she has professed a fondness for the “second movement” in classical music—the soft, quiet passages sandwiched between the energetic first movement and the emphatic, decisive third movement. Radigue’s magic is in finding the beauty in those points in between. She revels not in the sounds themselves, but in the process by which sounds grow and evolve. Through her music, we see that sounds are not discrete objects to be manipulated, but more like organisms with a life of their own, interacting with one another in complex ways. The more you listen—her work invites close listening—the more you become attuned to its gradual, thoughtful pace.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.