Hilton Als

Hilton Als

At the Met Museum, a centennial retrospective of Vogue’s fabled photographer.

Irving Penn: Centennial, installation view. Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Irving Penn: Centennial, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through July 30, 2017

It was my refuge. To walk through the immense doors at the Grand Army Plaza branch of the Brooklyn Public Library was, for me, to enter a version of Ali Baba’s cave, one where the walls were lined in dreams, possibility, and reason. Two or three days a week I’d cut school after lunch and start my real life or education in those library stacks. I was thirteen, and back then you couldn’t check many picture books out of the library, so on some of those afternoons—many of them—I sat in the section where they were kept. Snuggled up there, safe from the world that deemed such activities as “sissy,” I pored over Richard Avedon’s photographs of models conveying joy or distress. I spent hours with Irving Penn’s Worlds in a Small Room, a collection of images he shot in a makeshift studio on various trips to places like Dahomey (Benin), Morocco, and Paris, largely for Vogue, where, in 1943, the artist was hired, first, to come up with design ideas for the cover. Penn’s last sittings were published in the storied fashion magazine in 2009, shortly before he died, aged ninety-two.

Irving Penn: Centennial, installation view. Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sitting in those library stacks in Brooklyn, I marveled at what photography could do; images not only took me to different worlds, the best photographers also defined a world through their style, that mysterious thing that allowed them to make reality look less real and more like the reality of their imagination. The decades Penn spent producing portraits, still lifes, and other work for Vogue is an extraordinary achievement by any measure—even the protean Avedon, Penn’s only professional rival, lost his contract with the magazine in 1990. To be a creator working on a very high level month after month in a commercial context is nearly unheard of. Penn not only managed that—for years he had the institutional support and protection of Alexander Liberman, who was the editorial director of Vogue and other Condé Nast-owned magazines from 1960 to 1994—but his pictures, beautifully rendered gelatin silver prints that deepened the images’ blacks and grays, often added a certain gravity and moral seriousness to a magazine whose business was generally about other things.

Whereas the theater-obsessed Avedon seduced consumers through energy and storytelling, Penn’s studio-based work was about trying to make a moment in cinema when “nothing” happens other than the event of the star, lighting, costuming, all coming together in a still frame, a photograph. (His younger brother was the acclaimed filmmaker Arthur Penn.) He was interested in photography as a plastic medium, and how best to capture achievement as it had been gained through his subjects’ talent, physical beauty, and what have you. Penn started out as a fine art student at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, now known as the University of the Arts. He studied there with the fabled Russia-born graphic designer and photographer, Alexey Brodovitch. He bought his first camera in 1938 and used it to look for form in storefronts and graffitied walls. But unlike Walker Evans and Helen Levitt, Penn wasn’t interested in the political implications of what he was shooting; he liked those letters on the wall because they were visually arresting, almost pretty.

Irving Penn: Centennial, installation view. Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

At Vogue, Penn began shooting still lifes—plates of fruit, half-eaten meals, cigarettes crushed out near a glass of liquor. His pictures were always beautiful and stayed beautiful; they were never upset by his nerve endings, if he had any. Like many other photographers, Penn struggled, at first, with how to represent reality, but the question was heightened, of course, by the unreal reality of shooting fashion, working in the controlled world of a studio. Penn hit on something by hyper-stylizing his images, and making the viewer aware of the frame by foregrounding a sleeve, or cropping a close-up mid-temple so that one saw the pictures as pictures. He would become an architect of fashion and not another victim of it.

Unlike Avedon the portraitist, Penn did not try to upend fashion’s “pretty” rules when taking a famous person’s picture by calling attention to their flaws; he was interested in his sitter’s interiority, their natural or manufactured authority, and the graphic line of their shape as they submitted to what I’d call cinematography. Penn was a brilliant casting director. His eye for faces and what the body can and cannot do within the limits of the frame is apparent in many of the pictures that fill Irving Penn: Centennial, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s comprehensive retrospective. Dividing this eight-room show by theme—celebrity portraits, nudes, Vogue covers, and so on—the curators, Maria Morris Hambourg and the Met’s current director of photography, Jeff Rosenheim, display a good editor’s sense of how to distill Penn’s enormous output. But it’s not an exhibition that tries to sort out or elucidate Penn’s complexities. One gets the sense that whatever complexities he had were reserved for pictures that, for the viewer anyway, go politically deeper when, in the late 1940s, he was sent by Liberman to photograph other parts of the world.

Irving Penn, Cuzco Children, 1948. Platinum-palladium print, 1968, 19 ½ × 19 ⅞ inches. Image courtesy Condé Nast.

A selection of these pictures appears in the exhibit, the ones I pored over in the library so long ago. Setting up temporary studios in far-flung places like New Guinea, Penn sought to “reveal” something of societies not his own by showing how “we”—the peoples of the world—were all the same, but different.

How different? Forty or fifty years after those pictures were taken in Morocco, Chile, and so on, and many years after I encountered them in the Brooklyn Public Library, the world has gotten bigger, and visual ethnography has grown more complicated as the questions grow larger: Whose world are we looking at, and who’s doing the looking? One is first prompted to consider these questions reading the curators’ words in the wall text that accompany Penn’s portraits of various luminaries in the 1940s. In this series, the photographer positioned his subjects “between two angled stage flats [as] an effective way to control and amplify their responses . . . The sitters’ sometimes disproportionate body parts (such as Joe Louis’ narrow shoulders and enormous feet) call attention to the foreshortening distortions of the camera’s lens.” Reading this, one is reminded of that extraordinary passage in Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, when the “other” speaks of how he is perceived by the “white gaze”:

The Negro’s clothes smell of Negro; the Negro has white teeth; the Negro has big feet . . . I slip into corners; I keep silent . . .

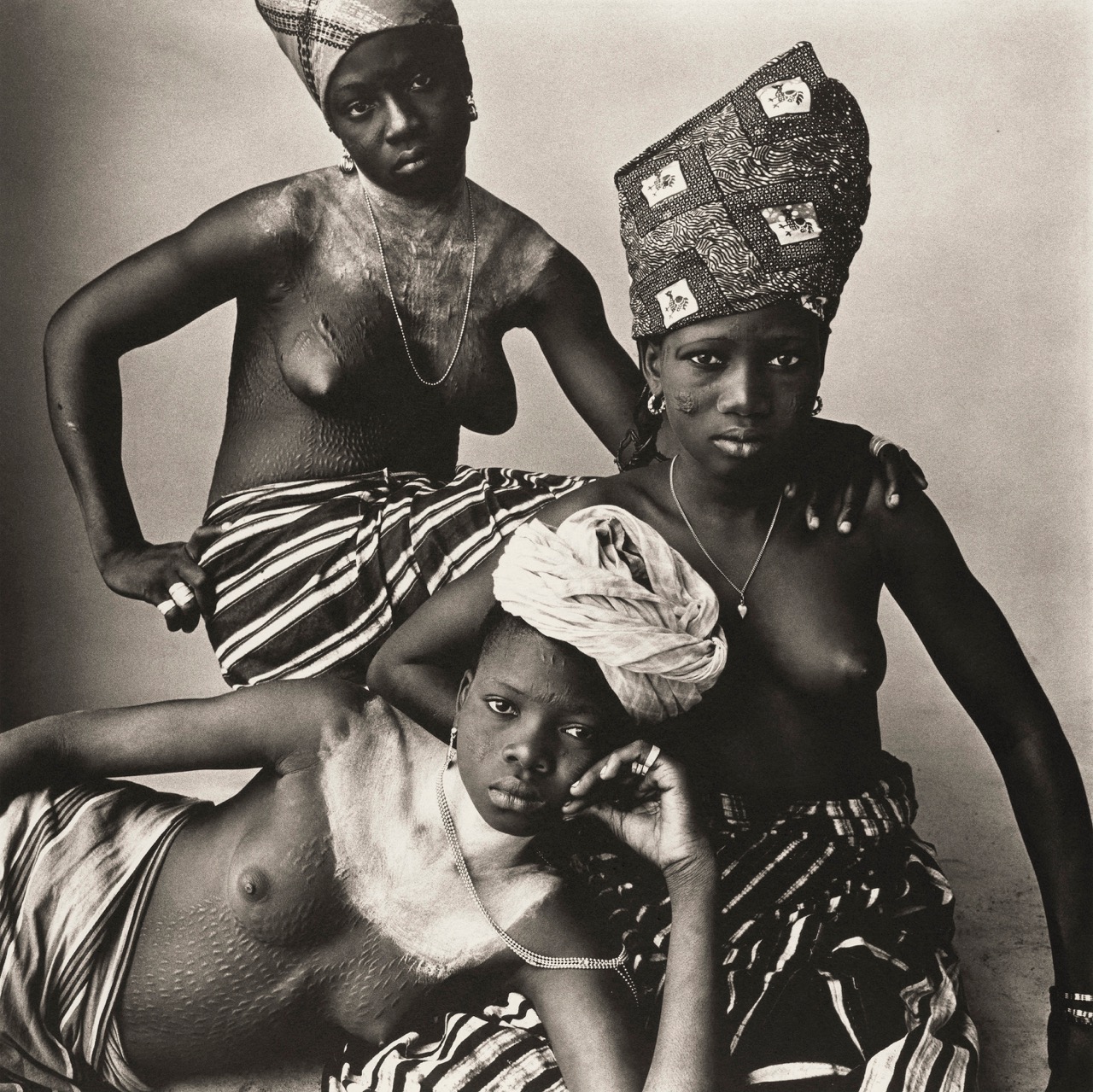

Irving Penn, Three Dahomey Girls, One Reclining, 1967. Platinum-palladium print, 1980, 19 ¾ × 19 ¾ inches. Image courtesy Irving Penn Foundation.

Moving on from Louis in that corner, one comes across the group of beautiful girls from Dahomey I first saw in Worlds in a Small Room, now freed from a book’s binding, elevated to the seriousness of a museum wall. Placed there it’s clearer that the young women were considered beautiful in the first place, perhaps, because they are Vogue worthy, but black at a time when models of color were not featured in the magazine. Their blackness—as seen by Penn—was allowed because they were “by” Penn, sealed off from context and history—but not the silence that permeates cinematography.

Hilton Als is a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine. He is the author of White Girls and is the co-author of Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor, and was awarded the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism.