Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

Past and present, art and activism: a documentary by Laura Poitras highlights Nan Goldin’s lifelong commitment to justice for the vulnerable.

Self-portrait with scratched back after sex, as seen in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. Courtesy Nan Goldin.

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, directed by Laura Poitras, opens in select New York theaters on November 23, 2022

• • •

In a personal essay / call to arms published in the January 2018 issue of Artforum, Nan Goldin, recounting her recovery from addiction to OxyContin and announcing her determination to hold accountable the Sackler family, the billionaire dynasty behind the opioid crisis, writes, “I went from the darkness and ran full speed into The World.” That declaration could just as easily serve as the artist statement of the renowned photographer, who in the late 1960s escaped a childhood home suffused with lethal secrecy and conformity and fell in with a crowd of marginalized beauties and geniuses—the androgynes, queens, fags, and dykes who would be the subjects of her coruscating, intimate photos, an oeuvre that would also repeatedly include Goldin herself as subject. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, Laura Poitras’s stirring documentary about Goldin, charts her past and present, a double-stranded, braided approach in which we see how her current-day activism is an organic extension of half a century living with and chronicling the vulnerable, the misfits, the outcasts.

Poitras’s film opens with scenes from the first demonstration organized by P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), the direct-action group founded by Goldin in part to go after the Sacklers. On a March afternoon in 2018, the photographer, now sixty-nine, and her comrades, many of them several years her junior, assemble by the Temple of Dendur, the enormous Egyptian structure that dominates the Sackler Wing of the Metropolitan Museum, one of the scores of cultural and educational institutions that have benefited over the decades from the family’s immense philanthropic largesse. P.A.I.N. members engage in protest-theater tactics honed in the ’80s and ’90s by ACT UP, an explicit model for Goldin’s organization: chanting stark rhymes (“Sacklers lie, thousands die”), tossing empty pill bottles into the temple’s reflecting pool, staging a die-in.

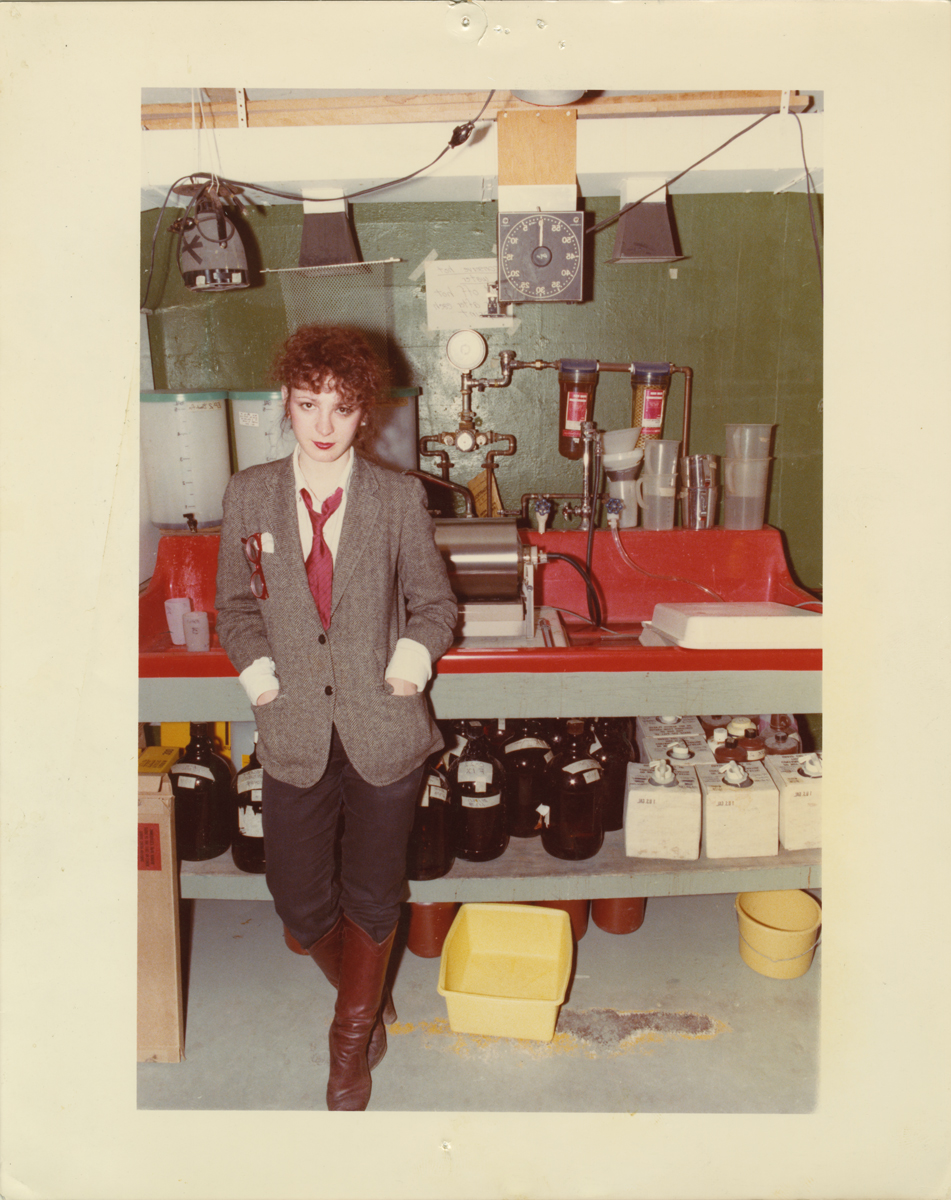

Over the next four years, Poitras captures P.A.I.N.’s planning meetings in Goldin’s Brooklyn home; its demos in museums around the world, all recipients of Sackler funding; and the group’s more recent efforts in harm reduction for drug users. No matter who is speaking in these scenes, no matter where the center of the action may be, the viewer seeks out Goldin, whose larger-than-life presence is belied by her elfin figure, topped with red corkscrew curls and usually clad in smart, simple all-black ensembles. Deepened by a lifetime of cigarettes (sometimes swapped for a vape pen), her voice is unfailingly authoritative.

Nan Goldin, as seen in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. Courtesy Nan Goldin. Photo: Russel Hart.

It is also unsentimental, matter-of-fact. However elated Goldin may be over P.A.I.N.’s extraordinary successes in having citadels of culture like the Met, the Louvre, the Guggenheim, and London’s National Portrait Gallery (among others) refuse Sackler money and/or remove the family’s name from its walls, she is fully aware that the battles may have been won but the war has still been lost. Earlier this year the Sacklers and their company, Purdue Pharma, reached a settlement requiring the family to pay $6 billion to ameliorate a crisis that to date has caused at least half a million deaths in the US alone and cost $1 trillion owing to overdoses and countless other miseries; in exchange, no civil claims can be brought against the clan. “This is the only place they’re being held accountable,” Goldin remarks soberly after that tainted surname has been scrubbed from seven of the Met’s galleries.

These present-day, P.A.I.N.-focused chapters of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed are undeniably rousing, even if Poitras on occasion tries to create—as she did so successfully in Citizenfour, her 2014 chronicle of Edward J. Snowden’s epoch-altering leak of damning NSA documents—nail-biting tension where none is needed, evidenced in an extraneous segment on a P.A.I.N. member being followed by a likely Sackler-hired goon. But the film’s deeper emotional heft emerges from Goldin’s recapitulation of her life, her off-screen narration illustrated by a bounty of archival material: harrowing medical records; outtakes and excerpts from films by the various No Wave and feminist eminences (Vivienne Dick, Bette Gordon) that featured Goldin and her downtown compatriots (notably the great Cookie Mueller); and the photographer’s own bewitching body of work, which could be defined as private acts made public.

Nan in the bathroom with roommate, Boston, as seen in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. Courtesy Nan Goldin.

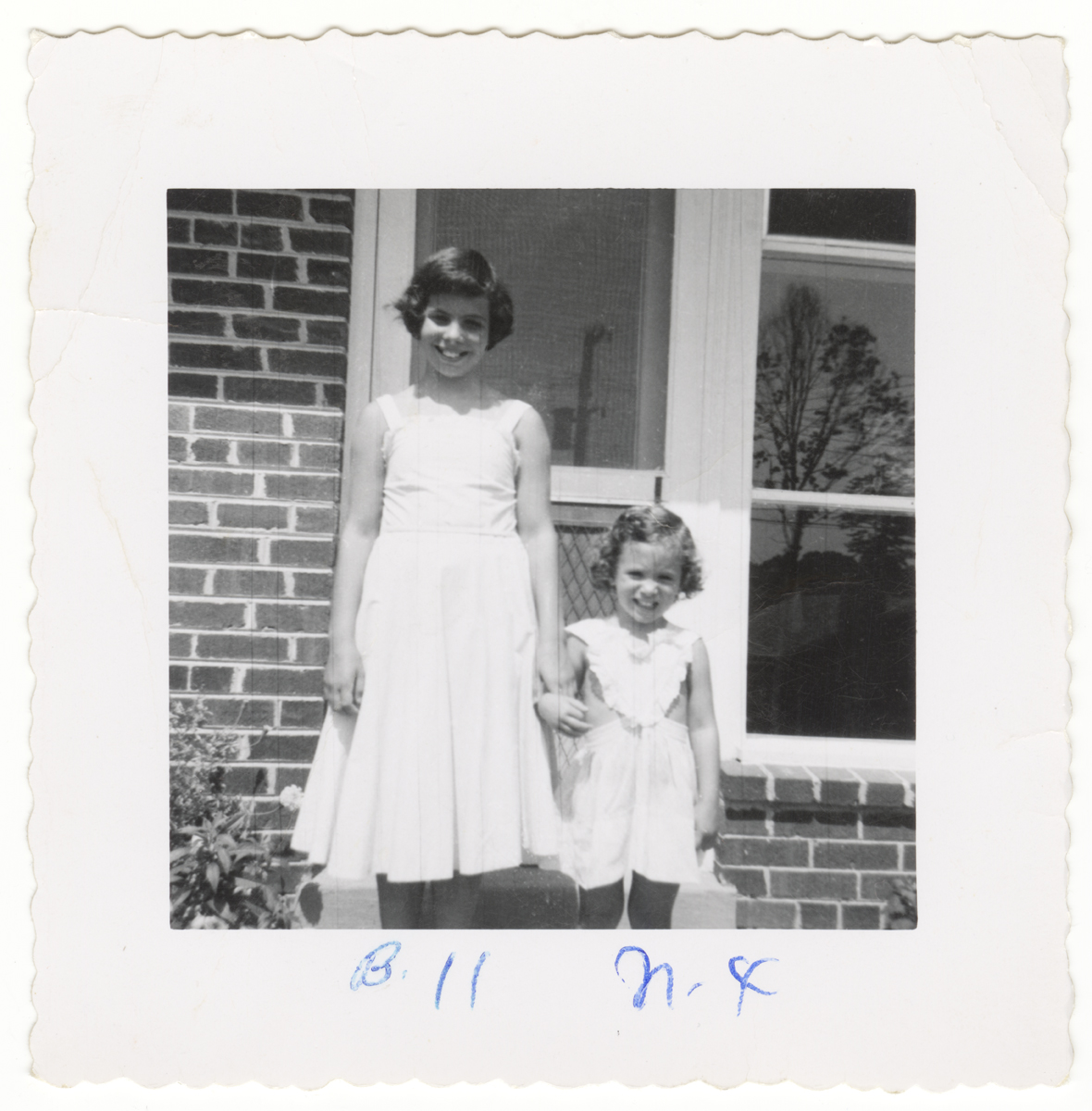

“It’s easy to make your life into stories. But it’s harder to sustain real memories,” Goldin says to Poitras (whose queries, puzzlingly, are often delivered in a near whisper) early in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. Goldin’s resolve to remember was likely forged in childhood as a response to her ill-equipped, deceiving parents, who insisted on covering up the suicide of Goldin’s beloved older sister, Barbara, as an accident. Barbara, who died in 1965, at age eighteen, looms over the film as its pneuma: a passage from one of her psychiatric evaluations supplies the documentary with its evocative title. Her elder sibling, insists Goldin—who grew up in the ’50s and ’60s on the outskirts of Boston—made her keenly aware of “the maddening and deadening grip of suburbia”; Barbara’s rebellion against this asphyxiating milieu was the “starting point” of Goldin’s own.

Nan and Barbara holding hands, as seen in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed. Courtesy Nan Goldin.

The photographer recalls her constellation of friends and lovers in downtown Boston, Provincetown, the Bowery, Berlin, and beyond—bohemian demiurges, many of whom would be immortalized by her Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1985)—with the same imperturbable voice as that heard when she speaks in a drab New York State Assembly hearing room on the necessity of funding for harm reduction. Goldin is against forgetting. Just as crucially, she is against nostalgia; there is no hint of wistfulness, for example, when she discusses pre-gentrified New York. Instead, she provides detail-rich accounts, serving as astute cicerone to fascinating, long-shuttered places in Manhattan, like Times Square’s Tin Pan Alley bar, many of whose employees were women who had once been sex workers—as Goldin was, a fact she has only recently disclosed and discusses candidly here. (Both Tin Pan Alley and an exceptionally charismatic Goldin feature prominently in Gordon’s Variety from 1983.)

Clear-eyed, Goldin reflects on other times that she fell into “the darkness.” All the Beauty and the Bloodshed shows us the velocity with which she has always come back, racing headlong into a wildly unjust world that she has endeavored—and succeeded—to make less so.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns and the author of a monograph on David Lynch’s Inland Empire from Fireflies Press.