Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Hobnobbing with fellow celebrities, international advocacy, and a bit about the music: Bono’s new not-quite-tell-all memoir.

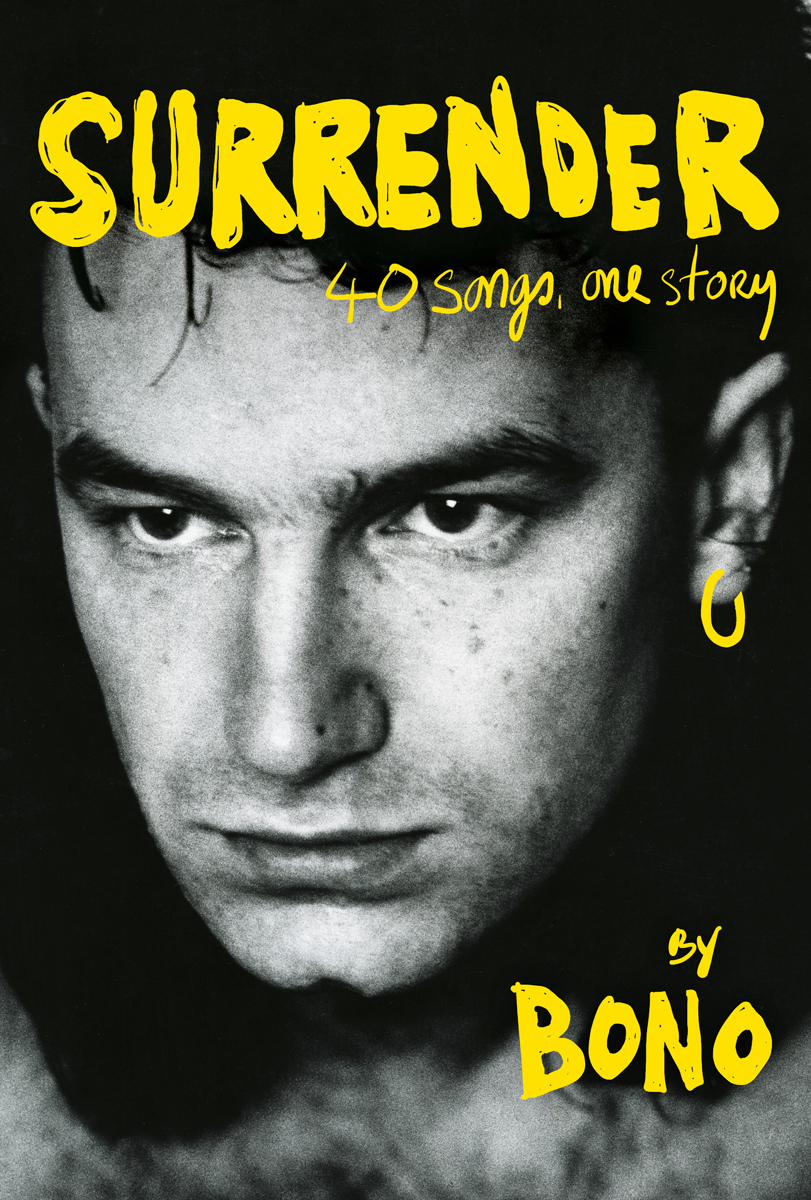

Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, by Bono, Knopf, 563 pages, $34

• • •

Few contemporary rock stars are as universally celebrated as Bono. Ever since his band, U2—formed with his teenaged schoolmates in 1976—grew massively in fame in the 1980s, he has been the quintessentially confident lead singer, an almost messianic performer with a burning desire “to be loved at scale,” as he confides in his new memoir, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story. To date, U2 has sold over one hundred seventy million albums and garnered twenty-two Grammy awards. The nearly six-hundred-page-long Surrender is Bono’s latest career milestone, fetching a mind-boggling book deal estimated at $8.4 million, according to the Irish Sun.

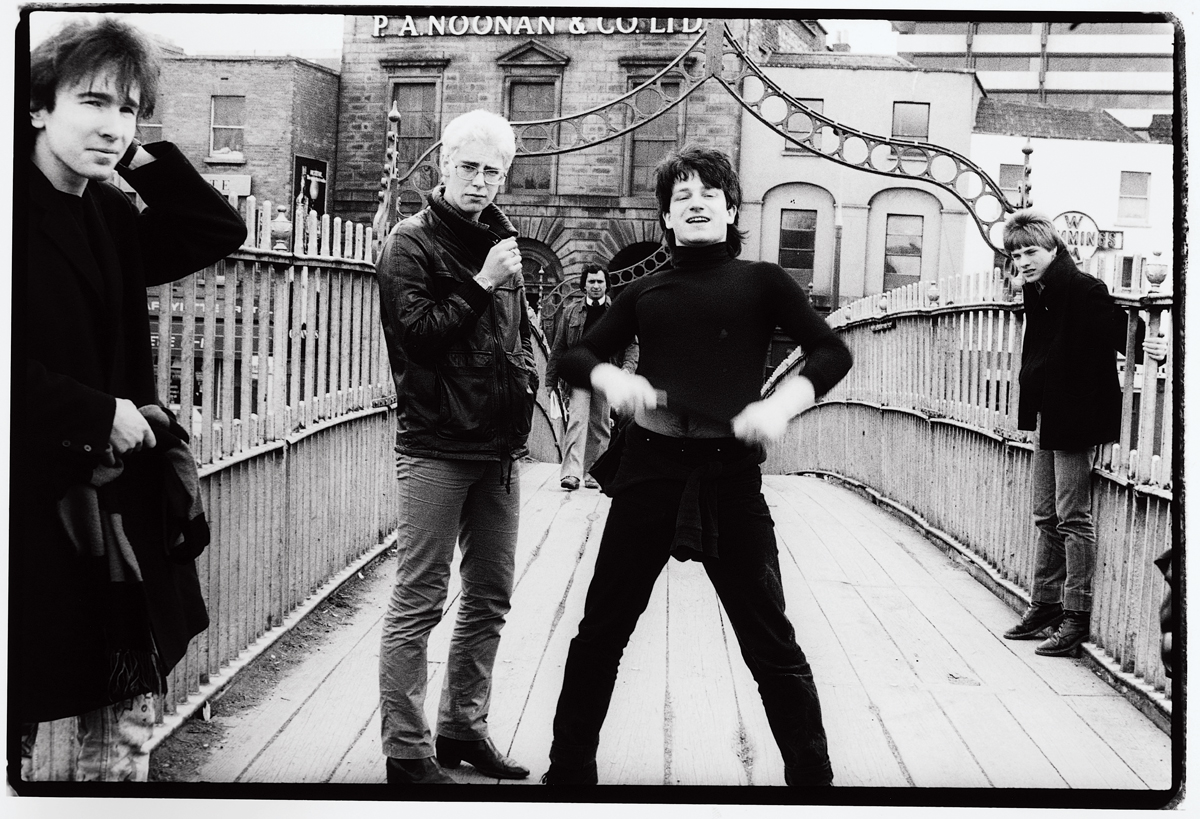

U2, Halfpenny Bridge. Photo: Paul Slattery.

Surrender follows Bono’s life story in a loosely chronological order, with each episodic chapter named for a different U2 song. In the first quarter of the book, he traces his multidenominational upbringing in Dublin (where he was born Paul David Hewson, in 1960); his mother’s untimely death, from a brain aneurysm she suffered at her own father’s funeral, when Bono was fourteen; and the early days of U2. His account of making one of the band’s first hits, “I Will Follow,” from 1980, is especially vivid. The rehearsal room, he writes, was less than a hundred yards from his mother’s final resting place. “ ‘I Will Follow’,” Bono remembers, was “about some kid who wants to find his mother, and even if she’s in the grave, he’ll follow her there.” Bono says he instructed the Edge, the guitarist, to “play the sound of an electric drill through the spinal cortex,” and offers little-known details into the song’s odd instrumentation: they “used bicycle wheels as percussion, turning the bike upside down in the hall of Windmill Lane and using forks and knives in the spokes for rhythmic effect. In a break in the track we threw milk bottles up in the air and let them bounce down the tiled hallway, their off-key musical contributions a novel addition.”

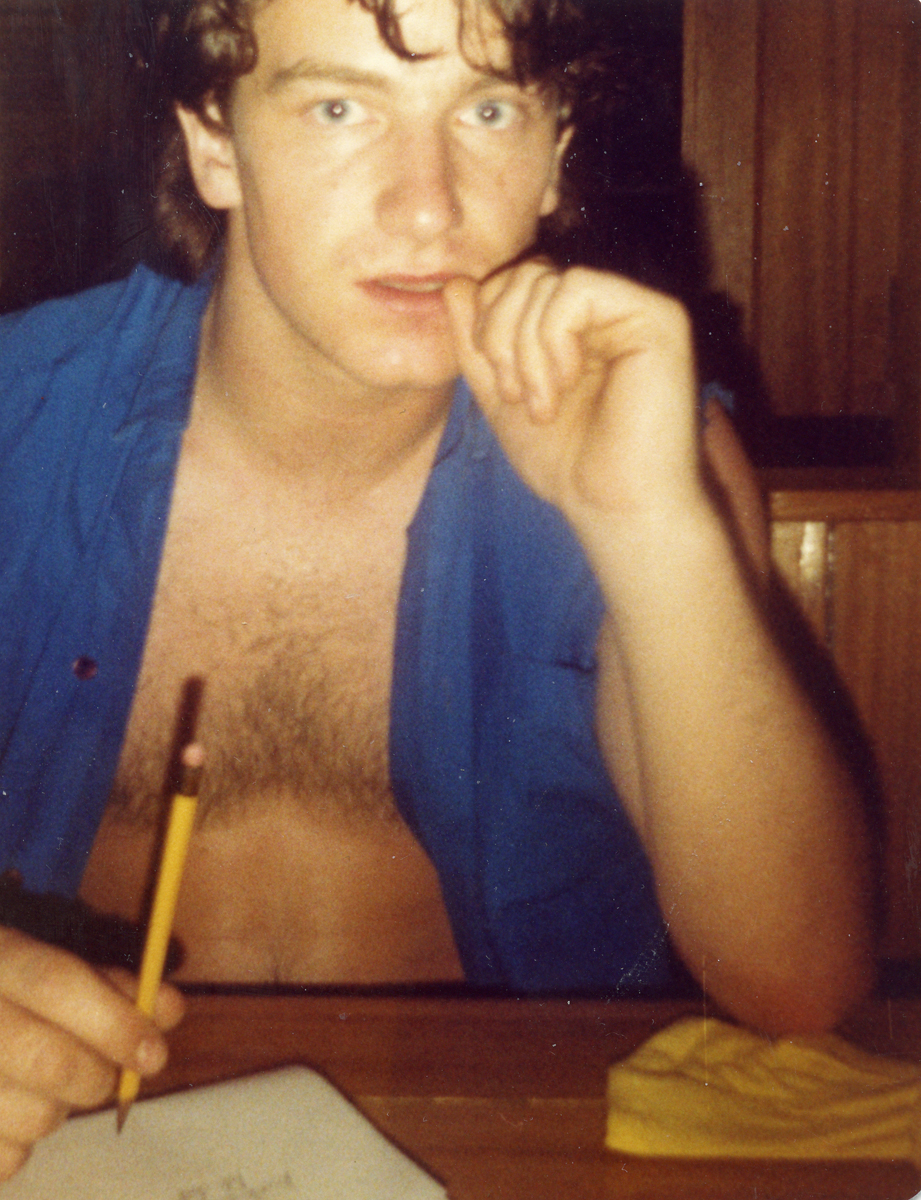

U2. Photo: Patrick Brocklebank.

The youthful exuberance and specificity of the first few chapters recede as the narrative progresses. Surrender doesn’t deliver much more about the process of making music after those early glimpses, which will be frustrating for some fans. There are brief passages that go behind the scenes of various U2 albums, with some entertaining anecdotes, but little in the way of any deep musical analysis. For instance, regarding Achtung Baby, released in 1991, he mainly writes about the dislocation and alienation of recording in Berlin at the cavernous Hansa Studios as the Wall was coming down—which fueled the record’s moody atmosphere, to be sure—but not that much about the songs themselves.

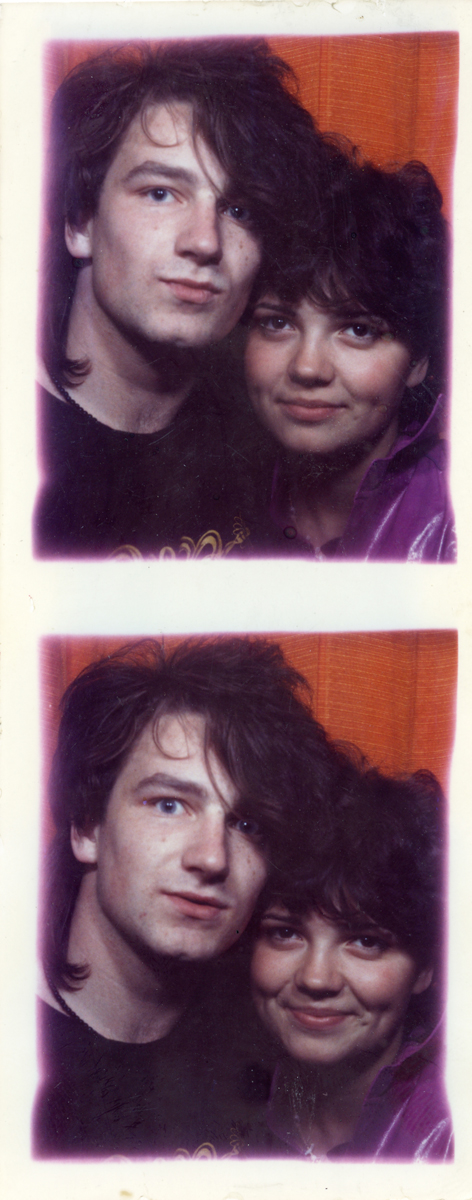

Ali Hewson and Bono. Courtesy the Hewson family archive.

So what does Bono talk about, if not music? Throughout the chatty, conversational book, he discusses the inner workings of his friendships with his bandmates, his relationship with his wife, Ali, and his belief in God. Sizable chunks of Surrender deal with international politics, including Bono’s long-standing advocacy work on behalf of AIDS activism and international debt cancellation. There are numerous stories of his famous acquaintances—world leaders, business titans, musical legends. We are regaled with recollections of hanging out in the Oval Office with Bill Clinton, going over to Steve Jobs’s house for tea, kissing the Pope’s ring, and drinking whiskey with Frank Sinatra. A celebrity perspective on other celebrities has the potential to be uniquely revelatory. But that is not the case here, as Bono, for the most part, offers only the breeziest of insights into the stars that stud his prose. When discussing other musicians, he favors grand statements but generally offers little explanation to back up his opinions. The trip-hop group Massive Attack, he declares, is “one of the most important bands in the history of music.” David Bowie “was England’s Elvis Presley,” in terms of impact. When he looks back on how Paul McCartney gave him a guided tour of Liverpool, the birthplace of the Beatles, Bono gushes, “It’s like Moses giving you a tour of the Holy Land. It’s like Freud giving you a tour of the brain. It’s like Neil Armstrong giving you a tour of the moon.”

Bono. Courtesy the Hewson family archive.

But here and there among the lofty pronouncements are little treasures, times in which Bono reveals himself to be a keen observer. In some of these short vignettes he manages to distill a given person’s essence through quick, trenchant descriptions. His concise commentary on Brian Eno, who coproduced several classic U2 albums, is particularly memorable, and it’s hard not to chuckle at tidbits like this one, about their studio work in the 1980s: “Brian abhorred ‘muso’ talk. We never used the word ‘riff,’ for example. He called it a ‘figure.’ A ‘guitar figure.’ He talked not about ‘sound’ but ‘sonics.’ ” And Bono’s account of his recent trip to Ukraine earlier this year to visit President Volodymyr Zelenskyy condenses significant emotional depth into a small amount of space. He highlights Zelenskyy worrying about Ukraine’s ability to continue exporting grain to poorer countries that rely on it—a poignant illustration of Zelenskyy’s humanism, persisting even in the face of disaster.

Bono and Ali Hewson. Courtesy the Hewson family archive.

These moments end up tipping the scales so that, ultimately, you very much feel that Bono passionately believes in the mythos he has created. The hyperbole can be hilarious, but also somehow poetic. Regarding a visit to Ethiopia, he rhapsodizes: “There is a mist lifting from the land. The red earth of Ethiopia is exhaling. The land is breathing. It is alive, only just, but alive.” Are these lines cringeworthy? Sure. But it’s precisely this sort of unselfconscious earnestness that led Bono to write songs with such engagingly epic grandiosity, songs with such universal themes that they seem timeless. At its heart, Surrender is really about Bono’s faith—whether it is faith in his band, faith in his marriage, faith in God, or faith in his ability to spark change in the world. Surrender is also about Bono’s unshakable belief in himself—the unstoppable self-confidence necessary to push forth to the highest levels of stardom.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.