Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

The pitiful vanities of men: a look back at the films of the veteran writer and director.

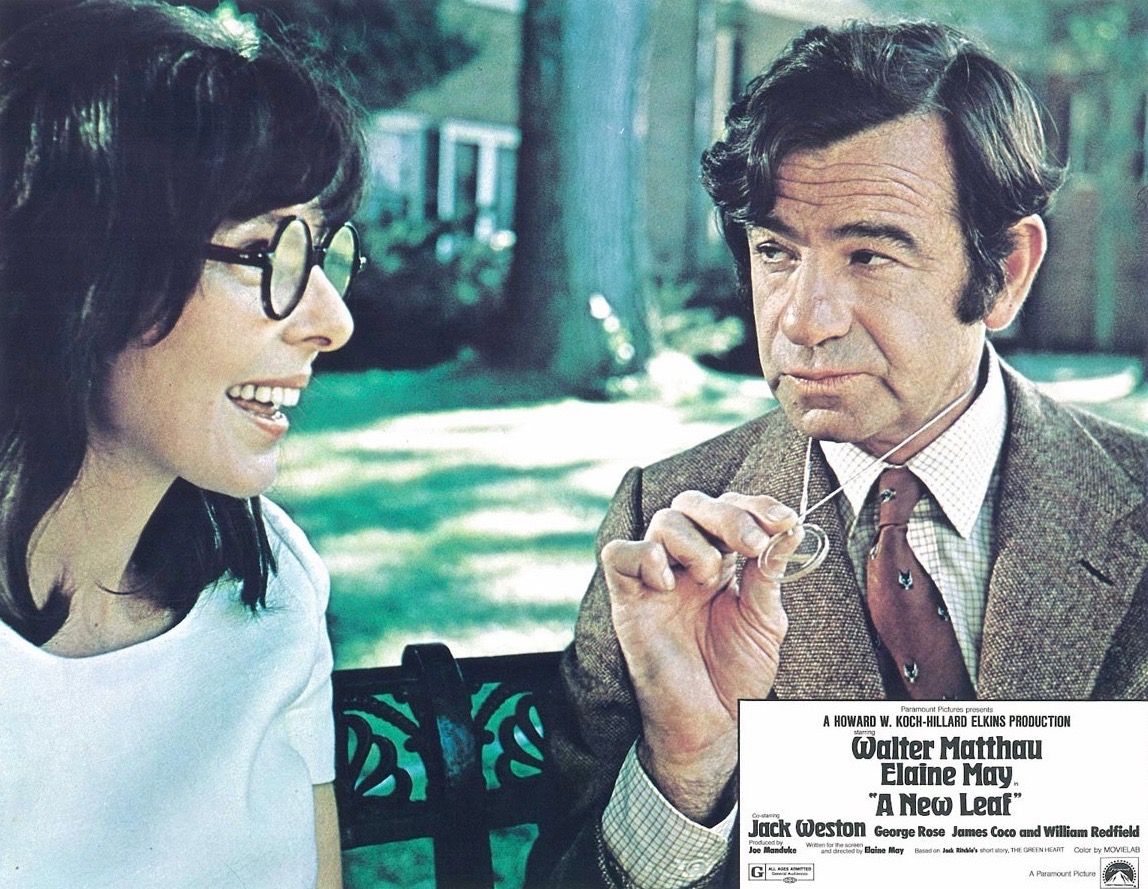

Elaine May as Henrietta Lowell and Walter Matthau as Henry Graham in A New Leaf. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures / Photofest. © Paramount Pictures.

“Elaine May,” Film Forum, 209 West Houston Street, New York City, January 22–February 12, 2019

• • •

Watching the comedies of Elaine May, I’m never sure which cracks me up more: the pinpoint absurdity of her throwaway lines, which sometimes take a second or two to process—did I hear that correctly?—or the immediate goofiness of her sight gags. The ear and the eye are continuously delighted in A New Leaf (1971), May’s first film as a director, which she also wrote and costars in. She plays Henrietta Lowell, an ungainly botanist whose inherited millions make her the mark of Henry Graham (Walter Matthau), a sexually ambiguous—or maybe just sexless—funds-depleted coxcomb who wants to wed her only for her money. Milling about in the background at a charity event where he first meets Henrietta, Henry says to an attendee, “Excuse me, you’re not by any chance related to the Boston Hitlers?” That outrageous off-hand remark is soon followed by this priceless vision: on her first date with the scheming toff, at the chic resto Le Pavillon, Henrietta gets up from the table and a hillock of bread crumbs falls from her skirt.

Included as a sidebar within the sprawling series “Far-Out in the 70s: A New Wave of Comedy, 1969–79,” Film Forum’s seven-movie tribute to May includes the four features she’s directed, one that she acted in, and two that she scripted. The mini-retro spotlights the work of a comic mastermind—among her many innovations, the duo she formed with Mike Nichols, in the 1950s, became the standard-bearer for improv comedy—whose career was tarnished for too long after the calamitous critical and commercial reception of her movie Ishtar (1987).

Elaine May as Henrietta Lowell in A New Leaf. Image courtesy Paramount Pictures / Photofest. © Paramount Pictures.

Born in 1932 in Philadelphia as Elaine Berlin, May (the surname of her first husband, whom she married when she was sixteen) was the daughter of actors; as a child, she performed with her father’s Yiddish-theater troupe. After Nichols and May dissolved their comedy act in 1961, she appeared in films, including Carl Reiner’s semiautobiographical Enter Laughing (1967); wrote and directed Adaptation (1968, an off-Broadway hit); and wrote an early screenplay—ultimately using a pseudonym, Esther Dale—for Otto Preminger’s bleak marital comedy Such Good Friends (1971; not in the Film Forum series).

Elaine May as Henrietta Lowell and Walter Matthau as Henry Graham in A New Leaf.

With A New Leaf, May established a theme that runs through the quartet of films she’s directed: the derangements of coupledom, whether sexual or platonic, with a breezy but still biting focus on the pitiful vanities and obtuseness of men. Witness the ridiculous white helmet Henry insists on wearing whenever he drives his red Ferrari—a running joke made funnier by the fact that the superfluous headgear is never remarked upon. The sports car is the only thing in the declassed swell’s life for which he evinces anything remotely close to erotic attachment. “I can engage in any romantic activity with an urbanity born of disinterest,” Henry boasts to his highly skeptical plutocrat uncle (James Coco) as he lays out his plan to nab a wealthy bride. The line kills, its zing heightened by the discordance between the averment’s grandiosity and Matthau’s native Lower East Side diction. Just as uproarious is May’s portrayal of guilelessness: her enormous spectacles always slightly askew, Henrietta is an endearing klutz, but she is never (or never only just) cute. As the plant doctor wildly flutters her hands to put on a pair of gloves, May showcases her gifts for orchestrating concise chaos—as opposed to broad, Borscht Belted gestures.

Charles Grodin as Lenny Cantrow and Cybill Shepherd as Kelly Corcoran in The Heartbreak Kid.

A deft comedy of humiliation, The Heartbreak Kid (1972), May’s next movie, more riotously highlights the pathologies of the couple. Although Neil Simon wrote the screenplay, the movie unmistakably bears May’s signature—not least for the fact that she cast her only child, Jeannie Berlin, born when her ma was just seventeen, as Lila Kolodny, who’s ditched by her schmendrick husband of less than a week, Lenny (Charles Grodin), for a shiksa college sophomore (Cybill Shepherd) while the new spouses are honeymooning in Miami Beach. Aggravating and unpolished, Lila nonetheless possesses more self-awareness than dissembling Lenny, the movie’s true fool. (After two viewings, I confess no love for the other May project set in Miami Beach, The Birdcage, from 1996; she wrote the screenplay for this exhausting, ultra-nelly, Mike Nichols–directed remake of the gay farce La Cage aux Folles.)

Robin Williams as Armand Goldman and Nathan Lane as Albert Goldman in The Birdcage. Image courtesy United Artists / Photofest. © United Artists.

For her third film, May switched genres but continued her piercing examination of dysfunctional dyads. A downbeat yet volatile anti–buddy movie, Mikey and Nicky (1976), which May also wrote, stars John Cassavetes as a low-level mobster in trouble who desperately summons a childhood pal (and fellow gangster), played by Peter Falk. The two leads, both phenomenal improvisers, brilliantly riff off each other as their characters’ long-festering resentments bubble up. May, a notorious perfectionist, wanted to give her actors all the space and time they needed to flesh out their scenes and shot more than one million feet of film—devotion met with wrath by Paramount Pictures, which threatened litigation.

John Cassavetes as Nicky and Peter Falk as Mikey in Mikey and Nicky.

The Mikey and Nicky fiasco derailed May’s career as a director for more than a decade. That hiatus ended with Ishtar, which she also scripted; her return to directing was made possible largely thanks to the intervention of her friend Warren Beatty, then among the most powerful men in Hollywood. Moviegoers of a certain age—Gen X and older—may recall, as I do, the horrible word of mouth that preceded Ishtar, a singular comedy about two spectacularly awful songwriters named Lyle Rogers and Chuck “the Hawk” Clarke (played by Beatty and Dustin Hoffman) who haplessly advance the cause of freedom fighters in a fictional North African emirate. Running way over budget and schedule—May insisted on numerous retakes in Morocco, where much of the film was shot—Ishtar was the subject of multiple tut-tutting news reports (like a New York magazine cover story from March 1987), which all seemed to condemn the movie, months before it even came out, solely for its excesses.

Dustin Hoffman as Chuck Clarke and Warren Beatty as Lyle Rogers in Ishtar. Image courtesy Columbia Pictures / Photofest.

I didn’t catch up with this film maudit until 2013, seeing it at BAM with a friend (and coeval) who, far wiser than I, had long been a fan. That screening remains one of the most memorable of my life, an event that provided the rare opportunity to discover a wildly unpredictable movie more than a quarter century removed from its initial ignominy. Ishtar’s genius operates on many levels: the painfully inept, unfailingly hilarious lyrics Rogers and Clarke concoct, several written by May (“Water! / My lips are on fire / with my desire / for you”); the bumbling twosome’s deluded but touching belief in their talent and each other (the pair of putatively straight guys are easily the most loving couple in May’s oeuvre); the scathing satire of Reagan-era foreign policy.

Ishtar is the last film May has helmed. Could she return to the director’s chair? May, now eighty-six, is currently starring on Broadway in Kenneth Lonergan’s The Waverly Gallery—her first appearance on a New York stage in more than fifty years. In a rare interview (shared with Nichols) she gave to Vanity Fair for its 2013 comedy issue, she said, “When I was very young, I thought it didn’t matter what happened to me when I died, so long as my work was immortal. As I age, I think, Well, perhaps if I had to trade dying right now and being immortal with just living on, I would choose living on.” Yet the need to make a choice has been obviated: May is immortal. May still lives on.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.