Maxine Swann

Maxine Swann

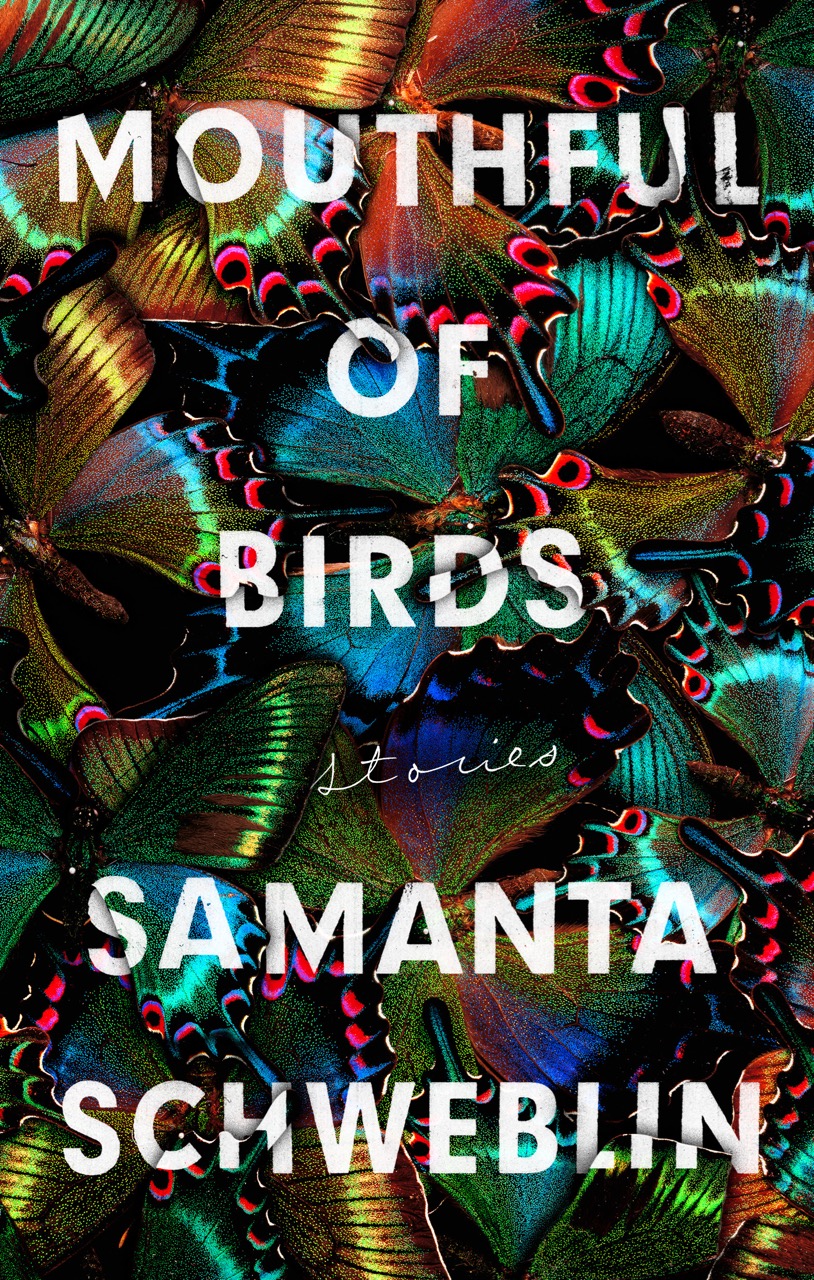

Horror of the butterfly: a collection of short stories by Argentine writer Samanta Schweblin.

Mouthful of Birds, by Samanta Schweblin, translated by Megan McDowell, Riverhead Books, 228 pages, $26

• • •

Recourse to the fantastic is part of an established tradition in Latin American letters, from García Márquez’s and Allende’s “magic realism,” where magical or supernatural events are casually introduced into otherwise realistic settings; to Borges’s dizzying, absurdist conundrums; to the gradual encroachment of the enigmatic in Cortázar’s world. Each writer bends reality differently. In step with her predecessors, Argentine Samanta Schweblin offers a vision predicated on the fantastic possibility, but she, in turn, has twisted it to her liking.

Schweblin has received numerous awards in the Spanish-speaking world since her debut story collection in 2002, and her first novel, translated into English as Fever Dream (the Spanish title was Distancia de rescate, or “rescue distance”) was short-listed last year for the Man Booker International Prize. Her second story collection, Mouthful of Birds, published in Spanish in 2009, is now out in English, translated by Megan McDowell. The English edition also includes a smattering of pieces from earlier collections, offering us a sense of her evolution as a writer. Schweblin works predominantly with fears—probing them, teasing them out, pushing them over the edge into full-blown, unnerving realities. The fantastic facet is usually, though not always, a form of nightmare come true that warps the otherwise prosaic lives of her unsuspecting characters.

The protagonists of Schweblin’s stories are going about their business—a father picking up his child at school, a fragile sister waiting for her protective brother in a seaside restaurant—when reality takes an unexpected turn. The father inadvertently damages a butterfly that has landed on him, then stomps on it to put it out of its misery, only to find that when the school doors open, this time not children but butterflies are released. Horror of all horrors, the wings of the butterfly he crushed are the exact same colors of the clothes his daughter was wearing that day. The sister sees a merman at the end of the dock. He’s a kitsch version of a certain kind of dream man with an “American pompadour,” but he appears to want and love her. Then her brother shows up, and, rather than staying by the merman’s side as she desires, she succumbs to her brother’s orders to get into the car, letting this once-in-a-lifetime chance for perfect love slip away.

The stories are most effective when they press a psychological point in a way that would have been impossible by non-fantastic means. Haven’t we all let this amazing chance for perfect love slip away?

Part of the reader’s pleasure is waiting for the surprise, the off detail that converts the banal moment into the anomaly. We are often not sure where the fantasy is located, inside or outside the characters’ minds. The stories thrive on this ambiguity: Is this really happening, or are we just in wobbly hands? As when a child’s logic is applied to a mother’s depression in “Santa Claus Sleeps at Our House”: she breaks out of her funk when her lover shows up, drunk and dressed as Santa Claus, on Christmas Eve.

In “On the Steppe,” a couple is trying to catch something out in the wild. An allusion to “fertility recipes” suggests that the object of desire is a form of offspring. When they meet another couple who were once engaged in the same pursuit and who’ve achieved their goal, they’re invited to that couple’s house for dinner, and we think the mystery will clear up. But the hosts won’t let their guests see the thing they’ve caught. When the husband finally sneaks away to find “it” for himself in a back room, he is horribly mauled.

The theme of reproduction gone awry, of monstrous children and alienated parents, surfaces throughout the collection. In a historical moment when Argentine women are fighting for the right to abort, the story “Preserves” strikes a particularly sensitive nerve. A young husband and wife reverse a pregnancy by nonviolent means with the help of a doctor’s formula that includes pills, changes in sleep patterns, and “conscious breathing.” Teresita, who was growing in her mother’s belly, shrinks back down until she is nothing more than an almond-sized object the narrator spits out and conserves in a jar to grow again when she and her husband are ready.

Argentine writers favor a more reined-in Spanish than their Latin American counterparts, and the energy of Schweblin’s prose, carefully replicated in McDowell’s translation, comes precisely from its pared-down quality. The stories, however, are only casually local. Argentine settings are nodded to but not elaborated (the truck stop in the middle of nowhere, the provincial train station haunted by dogs), as are local situations (no one ever has monetary change). While the regional quality may amplify the eeriness, it is not important to the functioning of the piece.

Schweblin has been publishing stories for seventeen years now, and the work has been evolving. If we occasionally sense in her writing an anxiety of form, some stories like sophisticated puppet shows controlled at arm’s length, her more recent productions are less rigid. The forms are more organic to the content rather than the predictable tension and snap. And the work has a new intimacy. She is closer to her characters and the characters are closer to each other.

A number of the stories here herald this new direction. In “Irman,” rather than any fantastic element, the conjunction of unusual circumstances and regular people behaving preposterously leads to an explosive tipping point. Two guys on the road pull over at a truck stop. One of them, the narrator, is desperately thirsty. Even though the place is empty, the extremely short waiter refuses to bring the drinks they’ve ordered. It transpires that the man’s wife has recently died, her body marooned on the kitchen floor. But she, being the taller party, was the one who usually got drinks down from the fridge attached high up on the wall flush with the cupboards. This totally fucked-up situation sets off a dark streak in the narrator’s otherwise pleasant companion: he ends up violently assaulting the waiter and stealing a box that contains not money, as he’d hoped, but a lifetime collection of the man’s private letters and mementos.

As her work matures, Schweblin is revealing herself to be most masterful, and her material most charged, when she is groping along the murky line between reality and fantasy, rather than out in the daylight performing the fantastic flash.

Maxine Swann is the author of three novels: Flower Children, Serious Girls, and The Foreigners. She has received a Harold D. Vursell Memorial Award from the Academy of Arts and Letters and her stories have been featured in The Best American Short Stories, O’Henry Prize Stories, and Pushcart Prize Stories. Born in Pennsylvania, she has been living in Buenos Aires since 2001.