Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

From Bulgarian Western to the latest from Agnès Varda: a look at six movies in this year’s cine-event.

New York Film Festival, Film Society of Lincoln Center, New York City, through October 15, 2017

• • •

Celebrating its fifty-fifth edition, the New York Film Festival, which began September 28, remains the city’s preeminent cine-event, a reason to log off from peak-TV content-delivery systems and commit to that increasingly audacious act: leaving the house. Highly curated, the NYFF unapologetically advances an argument: that the films assembled—at least the twenty-five in the Main Slate, chosen by a committee of four, and culled primarily from other festivals, notably Cannes—are the best of the year. Several NYFF regulars—Hong Sang-soo, Claire Denis, Noah Baumbach, and Arnaud Desplechin, among others—fill out this year’s Main Slate. But that exalted roster also includes a number of filmmakers making their first appearance at the festival.

During the first week of festival press screenings, which began September 18, I saw eleven films made in six different countries: ten from the Main Slate and one from the Spotlight on Documentary sidebar (Griffin Dunne’s Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, a by-the-numbers chronicle of his aunt), one of the many supplemental sections added to the NYFF in the past decade. Having consumed only a fraction of the titles on view—at least so far; press screenings continue through October 13—I can’t offer any grand statements about overarching themes. (But I wouldn’t have wanted to anyway; trend-spotting at film festivals is a fool’s errand at best.) Below, you’ll find the highlights of five mornings and afternoons spent in the dark: films by one NYFF éminence grise and the rest by auteurs making their Main Slate debut.

Faces Places. Image courtesy Cohen Media Group.

At age eighty-nine, Agnès Varda, the lioness of French cinema whose first feature, La Pointe Courte (1955), was a key forerunner to the nouvelle vague, has lost none of the curiosity and passion that have defined her films, especially her documentaries, over the past six decades. Her new nonfiction Faces Places, which Varda directed with the thirty-four-year-old street artist JR, recalls The Gleaners and I (2000), the elder filmmaker’s warm, incisive travelogue of la France profonde. “My greatest desire is to meet new faces and photograph them so they don’t fall down the holes of my memory,” Varda says at the outset of Faces Places. JR’s signature enormous black-and-white images, wheat-pasted on a variety of surfaces, of the people he and Varda encounter in villages like Bonnieux and cities such as Le Havre ensure that their interlocutors—miners, barmaids, dockworkers—will remain indelible. A sweet, but never cloying, portrait of an intergenerational friendship and artistic collaboration, Faces Places is also a matter-of-fact meditation on mortality. As Varda and JR scrutinize the headstones in the wee cemetery where Cartier-Bresson is buried, in the tiny town of Montjustin, the near-nonagenarian remarks that she’s looking forward to death because “that’ll be that”—Varda’s gallows-humor take, perhaps, on the legendary photographer’s notion of the “decisive moment.”

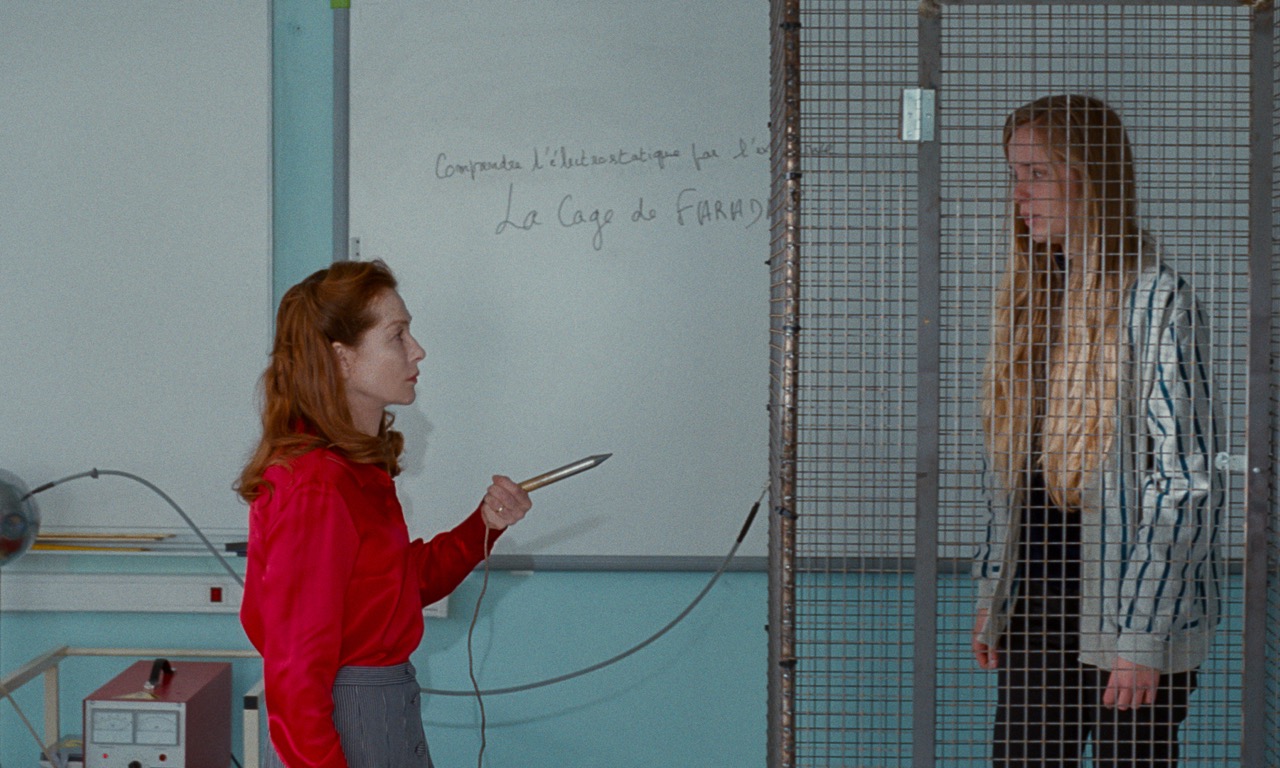

Mrs. Hyde. Image courtesy Les Films Pelléas.

Varda’s work, rightly, has often been featured at the NYFF; One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, her quasi-musical about the women’s movement that was the festival’s opening-night selection in 1977, will screen at this year’s edition as part of the Revivals program. One of Varda’s compatriots, Serge Bozon, makes his NYFF debut with Mrs. Hyde, a bracingly odd paean to pedagogy that’s been freely adapted from Robert Louis Stevenson’s gothic classic about a two-sided protagonist. As the beleaguered vocational high school physics teacher of the title, Isabelle Huppert displays her talent for impeccable screwball timing, skills she also demonstrated in Bozon’s previous feature Tip Top (2013). Like the earlier film, an unclassifiable policier that boldly combines slapstick with a shrewd analysis of the still-thorny legacy of France’s colonialist past, Mrs. Hyde upends categories while astutely calling attention to the country’s racism. The science prof’s students are almost exclusively young men of African and Arab descent: pupils from whom the least has been expected and demanded. Mrs. Hyde’s classroom directive—“Think, all of you, together”—should replace France’s national tripartite motto.

Félicité. Image courtesy Jour2Fête.

In Félicité, by the French-Senegalese filmmaker Alain Gomis, a durable genre—in this case, the maternal melodrama—veers into the oneiric. The eponymous character, played by Véro Tshanda Beya Mputu, who, like most of the cast, is a first-time performer, ekes out a living as a singer in a ramshackle bar in Kinshasa, the capital megacity of the Democratic Republic of Congo. After her fourteen-year-old son is injured in a road accident, she scrambles to raise the money needed for his hospital care. The indomitable heroine, facing down one humiliation after another and all number of venal officials, eventually begins to withdraw—into herself, into a copse that may exist only in her dreams. However porous the boundary between reality and fantasy may be in Félicité, the film, grounded by Mputu’s intricate weariness, never falters.

Western. Image courtesy Cinema Guild.

If Gomis’s movie might be thought of as an intervention in the “women’s picture,” Valeska Grisebach’s Western and Chloé Zhao’s The Rider lay bare, in different cultural contexts, the pitfalls of the cowboy mythos and other intractable modes of masculinity. Grisebach’s film, the title of which clearly announces the genre she’s dismantling, tracks the uneasy tension among a group of German men building a hydroelectric facility in rural Bulgaria and the strained interactions of the workers with the cautious locals. The effortlessly charismatic Meinhard Neumann, who suggests a Teutonic Sam Elliott, leads the excellent cast of nonprofessional actors in a movie that intelligently examines sclerotic machismo and the hegemonic creep of one wealthy nation over a poorer one.

The Rider. Image courtesy Sony Pictures Classics.

The Rider—set in the American heartland, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota—also features an ensemble of nonprofessionals, all playing fictionalized versions of themselves. Zhao’s film orbits around Brady (Brady Jandreau), a rodeo star recovering from a near-fatal workplace head injury—circumstances not too far removed from Jandreau’s actual biography. Filled with magic-hour widescreen vistas, The Rider neither romanticizes the economically perilous, physically dangerous profession of its protagonist nor condemns it, honoring instead Brady’s own complicated attachment to a calling that may kill him.

The Florida Project. Image courtesy Marc Schmidt and A24.

Of all the captivating neophyte actors I witnessed during my five-day film feast, though, none could top the sheer anarchic force of the pint-size troupe in Sean Baker’s The Florida Project. Imbued with the same kind of trashy buoyancy found in Baker’s Tangerine (2015), the director’s latest takes place in grim motel complexes—absurdly named Magic Castle and Futureland Inn—just outside Disney World. These abject lodges are home to six-year-old Moonee (Brooklynn Prince) and her pals Scooty (Christopher Rivera) and Jancey (Valeria Cotto), each the charge of a wholly ill-equipped or overburdened guardian. Without a trace of sentimentality, Baker’s film salutes the ineradicable fortitude that all kids seem to possess. The Florida Project bears out Lillian Gish’s maxim in Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955), another great film about tyke resilience that plays at the NYFF as part of its Robert Mitchum retrospective: “Children are man at his strongest. They abide.”

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns. From November 2015 until September 2017, she was the senior film critic for the Village Voice. She was a member of the selection committee for the New York Film Festival from 2009 to 2012.