Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

The fascinating paradoxes in Clint Eastwood’s directorial debut.

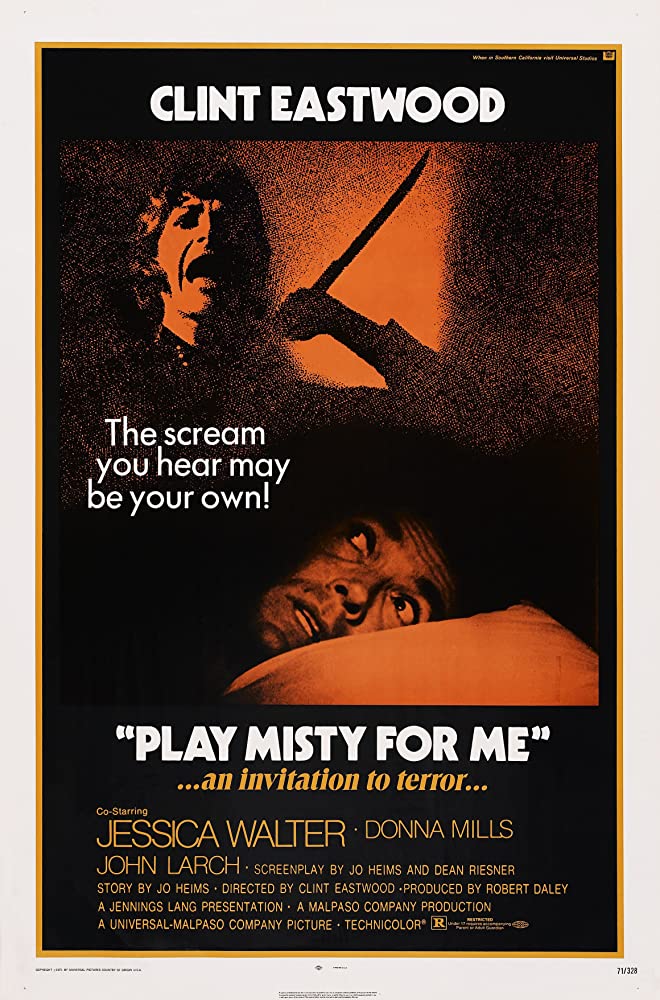

Play Misty for Me, directed by Clint Eastwood, available to buy or rent on Amazon Prime Video, Google Play, iTunes, Vudu, and YouTube

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that most movie theaters around the country remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

The opening sequence of Play Misty for Me, a film from 1971 that marks the directorial debut of Clint Eastwood, who also stars, may be the most beautiful I have ever seen. Swooping aerial photography captures the majestic coastline of central California’s Carmel-by-the-Sea, enormous whitecaps crashing against the rocks. Within this awesome natural splendor, a lone figure first appears as a speck then comes sharper into focus. It’s Eastwood, forty at the time of filming, and nearly as beautiful as the setting that engulfs him. Playing a local jazz deejay named Dave Garver, he stands forlornly on the deck of his former girlfriend’s temporarily vacated cliffside house in the Carmel Highlands. He stares below at the Pacific’s ceaseless swirl, walks up some steps, and peers inside, noticing a not especially accurate or flattering portrait of himself on an easel, the work of the woman whose absence he finds, but can’t bring himself to admit, unbearable.

This scene segues to one that counters what we have just seen: the ruggedly handsome man, initially so vulnerable, so small, transforms into a virile free spirit. Dave gets into his Jaguar XK150 and zooms down Highway 1, the car radio blasting a jazz-fusion instrumental called “Dirty Boogie.” He’s a lone wolf in black wraparound sunglasses. He can detour twenty-six miles south, crossing Big Sur’s Bixby Creek Bridge, before turning back to clock in for his 8 p.m. to 1 a.m. slot at radio station KRML. He can do whatever he wants.

But a complication enters Dave’s unfettered life: Evelyn (Jessica Walter), a fan of his show—her call-in request for the Erroll Garner jazz standard provides the film’s title—with whom he has a one-night stand. Breezily in accord at first with Dave’s insistence on a no-strings-attached arrangement, Evelyn is quickly revealed to be a stalker, a psychopathic prototype for other single, sexually active women unhinged by their all-consuming possessiveness, like Glenn Close’s Alex Forrest in Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction (1987) and other female lunatics in movies far inferior to Eastwood’s.

Evelyn’s machinations become more diabolical once she discovers that Dave has reunited with his ex, Tobie (Donna Mills), who returns to Carmel after four months in Sausalito, a sojourn undertaken mainly to recover from Dave’s philandering. “The thing I hate the most in the whole world is a jealous female. And that’s what I was starting to be,” she tells him during one of their many beachside walks, as Dave delicately broaches the possibility of getting back together. And thus Evelyn isn’t repellent or dangerous simply because she’s mentally ill. Her repugnant qualities are gendered: she represents female neediness in extremis. To paraphrase one of Susan Sontag’s more celebrated lines: I am strongly drawn to Play Misty for Me, and almost as strongly offended by it. That is why I want to talk about it.

Like most movies that imprint themselves on me, that I can’t shake, Play Misty for Me is a tangle of contradictions—a quality shared by many studio-backed movies from the ’70s, that confounding decade that saw as many advancements as retreats in the US for women’s rights (not to mention civil rights and LGBTQ liberation). I think of Eastwood’s movie as the bizarre fraternal twin of, or the gender inverse of, another film released the same year and one that evinces similar anxiety around second-wave feminism, then cresting, and women’s sexuality more generally: Alan J. Pakula’s Klute. That movie was as crucial a project for star Jane Fonda, who won an Academy Award for her performance as the boho-chic sex worker Bree Daniels, as Play Misty for Me was for Eastwood, who was not only directing for the first time but also playing a part far removed from the cowboys and bounty hunters that had established his reputation.

Like Eastwood’s movie, Klute is structured by a perverse triangle, consisting of a loving couple and a maniac who menaces the principal character: in Pakula’s film, Bree grows emotionally attached to the eponymous private detective played by Donald Sutherland, who’s protecting her from a serial killer who was once her client. Both films are punctuated by the terrifying peal of a rotary phone, a lunatic on the other end. Each boasts incredible footage of its respective locales. With its shots of Hell’s Kitchen, where Bree lives, Klute could almost be a city-symphony; abounding not only with littoral landscapes but also the flora of the Monterey Peninsula, Play Misty for Me doubles as a nature documentary. (Eastwood was so devoted to Carmel that he served as mayor of the town from 1986 to 1988.) One other link, which I didn’t notice until revisiting Eastwood’s movie last week: Walter and Mills both sport shag haircuts, variants of the coiffure indelibly associated with Fonda during the early ’70s.

In Klute, Bree works through her irreconcilable feelings—about sex work, about her acting aspirations, about her affection for the P.I.—in her analyst’s office. Bree, an imperfect but enduring emblem of women’s liberation—played by the most left-leaning, politically outspoken star of the time—is quite literally rescued by a man. The traditional roles of savior and saved obtain, as they do in Play Misty for Me; Dave must protect Tobie, in addition to himself, from Evelyn. But the image of Dave as macho defender—or of Eastwood as a paragon of masculinity—isn’t so clear-cut. Twice the actor is filmed in various states of undress, once without a shirt, another time in nothing but white briefs. His body is sexualized, fetishized, subject to a lubricious scrutiny usually reserved for actresses.

Here I should note that in addition to the fascinating, generative paradoxes found within Play Misty for Me, the film also stirs up my own roiling incongruities. A staunch lesbian supremacist, I find Eastwood’s duende undeniable. My deep indifference to heterosexuality vanishes during an alfresco love scene between Dave and Tobie, scored to Roberta Flack’s empyreal rendition of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” which plays in its entirety.

But now I must admit to other conflicting, overwhelming feelings, prompted by writing this piece. My initial viewing of Play Misty for Me, almost three years ago to the day, took place at Manhattan’s Metrograph theater, where the film was projected on 35mm and where I sat surrounded by at least fifty other people. The film has remained so alive in my mind largely owing to the conditions in which I first saw it. While rewatching it, at my dining room table as an audience of one, I couldn’t stop thinking about those strangers I convened with on Ludlow Street on that April day of 2017. I hope they’re all okay. I hope you are, too.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.