FT

FT

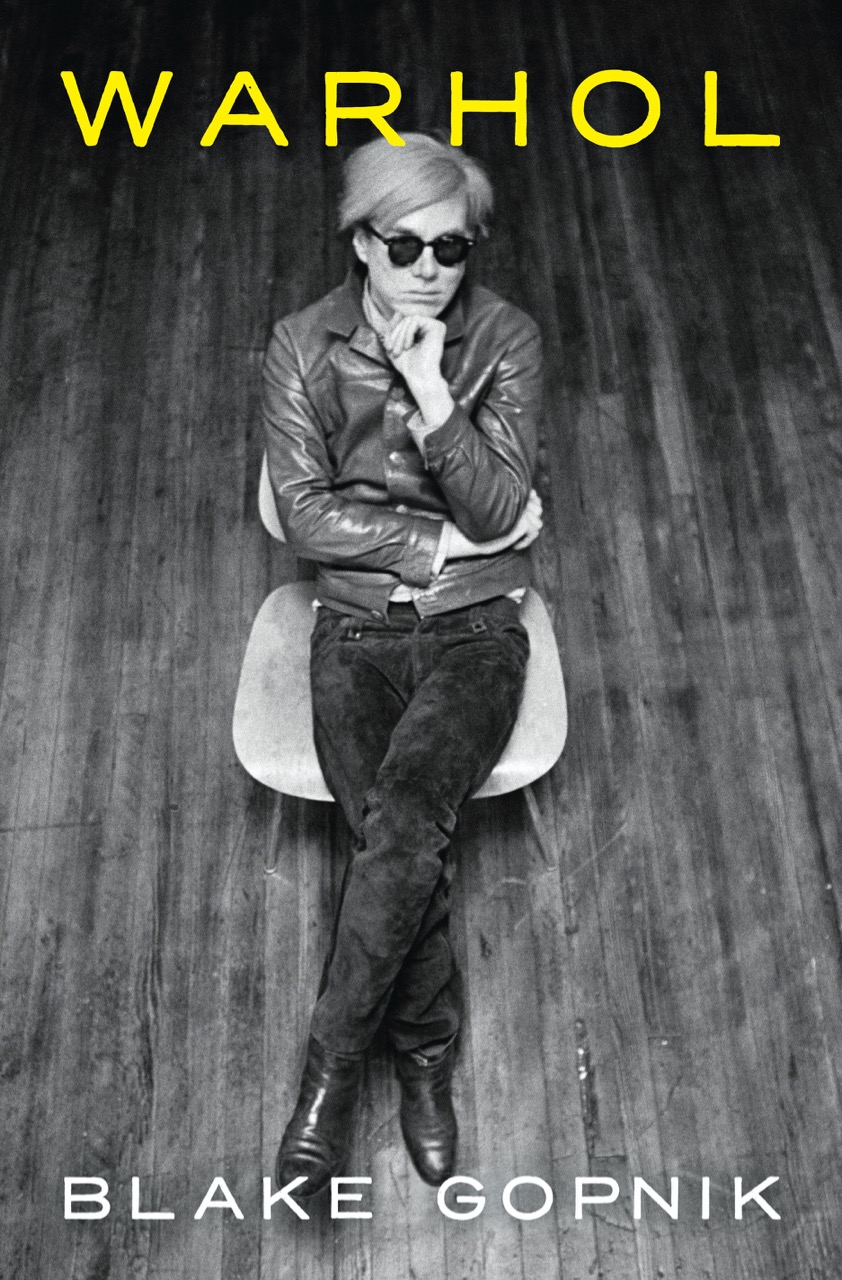

Blake Gopnik offers a massive biography of the artist and icon.

Warhol, by Blake Gopnik, Ecco, 961 pages, $45

• • •

Warhol, a new biography by Blake Gopnik, is a huge, meticulous tome. It has to be, to account both for Warhol’s unparalleled influence and for his sheer output. The portrait of Chairman Mao alone produced some two hundred canvases and 2,500 signed prints. In addition to silkscreens and paintings, the artist’s body of work includes drawings, guerilla audio recordings, experimental films, and piles of Polaroids; in each medium he left a significant mark. But Warhol’s leftovers aren’t limited to fine art. He was a compulsive shopper and hoarder who kept an exhaustive record of his activities, earnings, and expenditures, not to mention a vast trove of ephemera. Later in life he was known for sweeping everything on his desk into a box: 610 of these “time capsules” are now at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

This cornucopia allows Gopnik to reconstruct the texture of his subject’s life more deeply than most biographers can; he takes full advantage. The level of detail is impressive, though I’m not sure I needed to know how big Warhol’s dick was (I won’t spoil it for you). The research in Warhol is so expansive, in fact, that the copious endnotes are almost as long as the book itself, and only available online as a PDF. It’s not an ideal way to read a scholarly text.

Warhol, born into poverty in Pittsburgh in 1928, had a work ethic driven both by an obsession with money and by a deep need for artistic acclaim. The through line of Gopnik’s book is Warhol’s constant, brilliant, and often ridiculous effort to satisfy these hungers. There’s no contradiction between the drives, no opposition between an authentic artist sincerely expressing interiority and a calculating brand manager seeking to maximize profits. You don’t need psychoanalysis here: spend time with living artists and you’ll quickly see the intimate link between creative production and its economic base. That’s what Warhol’s art is really about.

Without sounding contrarian or condescending, Gopnik pushes back against simpler, standardized takes on Warhol. Sharp and prescient though his observations about late capitalism were, the artist’s art wasn’t about “consumer culture” or “commodities” in any vast, abstract sense. The paint-by-numbers canvases of the early ’60s don’t rupture some imagined division between high and commercial art, as many museum wall labels tell us; those works slyly suggest that Warhol, like his contemporaries, follows a formula for commercial appeal. Naming his studio “the Factory” wasn’t just a running gag about postwar mass production of soup cans and celebrities; it was a cunning insight into the increasing value of scaled production at a time when the work of art began to be not merely a commodity, but a commodity for speculation.

In his efforts to sell whatever he was marketing that year, Warhol was aided by an impressive and very New York network of contacts, allies, mentors, and sexual partners, many names appearing on several lists. In later years he welcomed the myth of himself as a brazen outsider invading the uptight art establishment, but the myth is false: from the beginning, Warhol was an insider. Improbably, he was briefly in a band with La Monte Young. Even more improbably, his most famous celebrity icon, Marilyn Monroe, was part of the artist’s extended circle and a regular at his favorite Upper East Side bar.

The art school acquaintances through which Warhol established himself as an illustrator in New York were the very same contacts through which he connected with New York’s uptown homosexual milieu, which in turn circled back to the art world. I’m not sure the average reader will care who was an assistant at which gallery in 1961, or how much money Robert Rauschenberg was making at various points in his career, but to anyone interested in the material and financial history of the art world, or in the sausage-making details of the postwar art school–to-gallery pipeline, Warhol will be invaluable. As of this writing, the gallery system that coalesced around the time of Pop Art’s dominance is still largely in place.

Dick size notwithstanding, Warhol eschews both sensational revelation and armchair psychologizing. Andy’s strategy was never to hide; he stayed mysterious by spilling so much in so many directions that nobody really knew what to make of him, though Gopnik’s is a Herculean and evenhanded effort. Most illuminating is the discovery of a highbrow education beneath the indifferent and ignorant facade he erected for public consumption. This erudite, intellectual Warhol, discoursing with friends about high-concept art and John Cage’s musicology, is the least familiar to me of the artist’s avatars. Friends assure us that Warhol could drop his oh-uh-isn’t it fabulous? persona at will, and in the earlier years of his fine-art career often did so in private. By the end of his life, even Warhol’s closest associates seemed unsure what was real and what was pretend. Maybe Warhol was, too.

Arranged chronologically, Warhol is over nine hundred pages long, but the 1960s occupy fully 515 of those pages, and not until page 709 do we reach 1970. The last seventeen years of Warhol’s life, almost half his professional career and fully two-thirds of his fine-art career, are given short shrift. Glossing over the sordid details of Warhol’s adventures at Studio 54 is forgivable—his diaries and Bob Colacello’s memoir Holy Terror (1990) can flesh out that era for you. But Warhol continued to produce astounding new work in later years, even as his stammering, starfucking persona remained unchanged. There were groundbreaking experiments with television and computer art; a surprising turn to Abstract Expressionism with the Oxidation series; and an advent of Catholic themes in his final finished canvases, the Last Supper paintings. Gopnik’s assessment of the early-’70s Maos as merely a new iteration of the “celebrity culture” commentary begun with Liz and Marilyn is lacking: in the same era Warhol painted Mao, he also painted hammers and sickles, even as Nixon was flying to China.

Given the extensive treatment of Warhol’s early connections with the city’s gay demimonde, fairness demands more coverage of New York during the AIDS epidemic. Warhol is as much a history of New York’s gay life as it is a history of New York’s art world: we see him embrace the urbane camp of the ’50s; watch him bounce between the refined milieu of the Upper East Side and the more militant West Village in the ’60s; we follow him into the BDSM dens and club world of the ’70s. The sense of absence in the ’80s is disappointing, if only in comparison.

This drift between cultural niches is intimately tied both to Warhol’s creative evolution and his personal transformations. There was nothing naïve about Warhol’s shifts, each aimed at attracting the attention of the crowd he most wanted to adore him while retaining a vanguard marketing edge. Warhol’s true genius lay in his ability to borrow and twist the mores and habits of each new scene, spinning them into something different enough to be interesting and pushing him toward his next source of inspiration. Dalí and Duchamp had long since invented the artist as brand, but Warhol invented the artist whose brand lay in a free-wheeling movement between forms, looks, and styles, infusing each one with value through his own iconic celebrity.

FT isn’t a real person, but that doesn’t seem to stop them from having a lot of opinions. You can find their work online.