Melissa Anderson

Melissa Anderson

In Otto Preminger’s 1975 curiosity, five hostages and many incongruities.

In red shirt: Kim Cattrall as Joyce Davenport in Rosebud. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

Rosebud, directed by Otto Preminger, available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber March 30, 2021

• • •

In the first half of his five-decade career, the director and producer Otto Preminger (1905–86) helmed several touchstones in a wide variety of genres: noir (Laura, 1944), the musical (Carmen Jones, 1954), the courtroom drama (Anatomy of a Murder, 1959). He launched the star trajectories of soon-to-be-icons, like Jean Seberg, a native Iowan chosen by Preminger from among 18,000 aspirants for the title role in his Saint Joan (1957). He cast the already famous in unexpected parts, as he did with Frank Sinatra, who played a heroin addict in The Man with the Golden Arm (1955)—one of many projects with taboo themes that Preminger took on, helping to render the priggish Production Code obsolete.

I am drawn not to the heights of Preminger’s oeuvre but to the oddities and misfires that clot his late-period output. These flops include Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965), a bizarre London-set mystery featuring a cast consisting of not only the blank, blandly attractive American actors Keir Dullea and Carol Lynley as orphaned siblings with a byzantine backstory but also fruity British eminences in supporting roles, such as Noël Coward as a landlord accessorized with a Chihuahua named Samantha and a vast collection of S-M accoutrements. That curiosity was followed three years later by the even more outlandish Skidoo, the squarest head-movie ever made, one partially inspired by Preminger’s own experimentation with LSD.

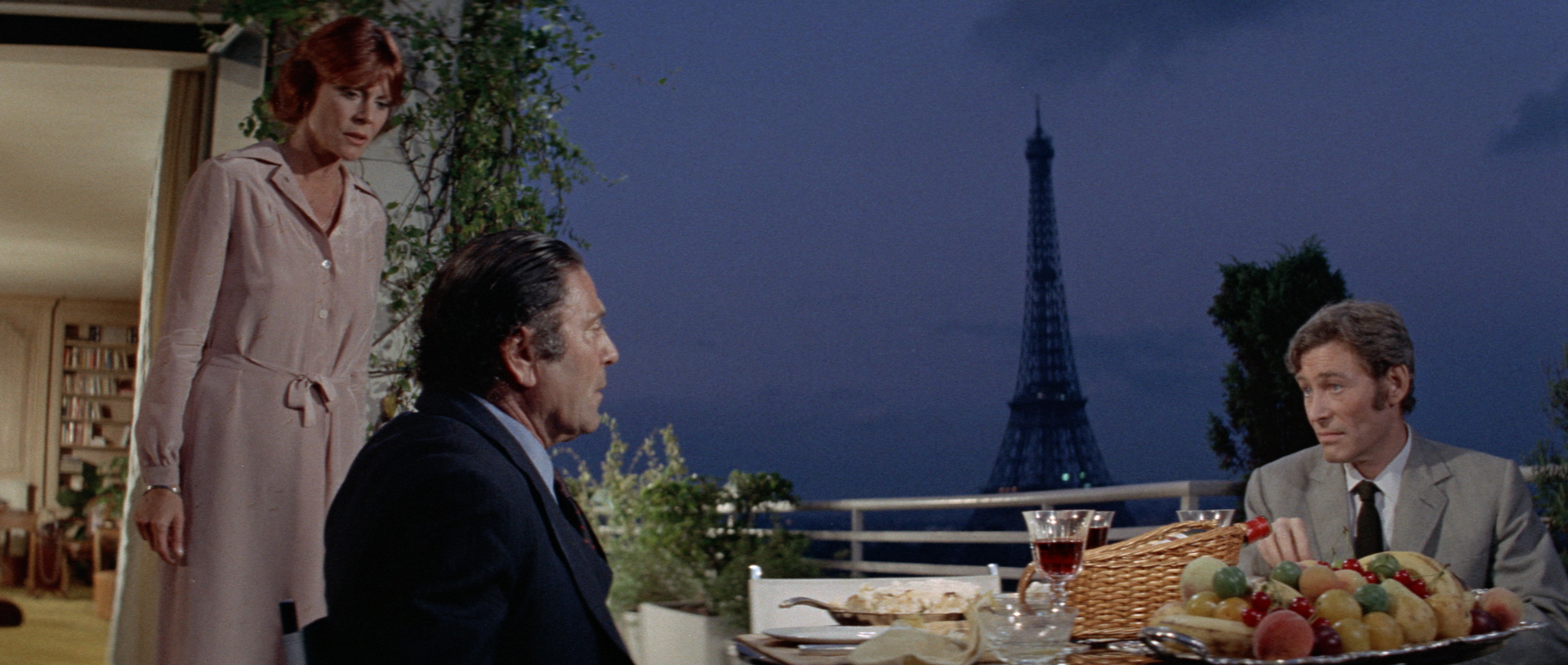

Center: Peter O’Toole as Larry Martin in Rosebud. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

But Preminger’s penultimate movie, Rosebud (1975), rarely revived, had long eluded my viewing; that gap is now blessedly filled, thanks to Kino Lorber’s release of the film, in a brand-new 2K master, on home video. Dense with often incomprehensible plot, this international suspense epic centers on British CIA agent Larry Martin (Peter O’Toole) and his quest to rescue five young women—all from highly influential families in politics or business—who have been kidnapped from the yacht of the title by the Palestinian Liberation Army.

The element that has always fascinated me about Rosebud is that two members of this imperiled quintet are portrayed by actresses I’ve loved for decades, each a titaness in her own right: Kim Cattrall, who made her screen debut in Preminger’s movie and was only seventeen at the time of filming (and twenty-three years away from being part of Sex and the City’s famous quartet), and Isabelle Huppert, three years older and with more credits than her costar but still shockingly baby-faced, almost impossible to imagine as the she-deity of auteurist Continental cinema that she would become. To see them together, in their only shared project to date, so early in their careers provides the film both its purest delight and its greatest frustration; there aren’t enough scenes devoted to them, though Huppert’s Helene, the first of the pentad to be set free, has the most screen time of her sister-hostages. (The other three are played by Brigitte Ariel, Debra Berger, and Lalla Ward.)

Left to right: Lalla Ward as Margaret Carter, Peter O’Toole as Larry Martin, and Isabelle Huppert as Helene Nikolaos in Rosebud. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

Yet Rosebud offers other thrills, too, especially for those who cherish incongruities. First among them: several members of the PLA—who gather at a safe house in Corsica, the cellar of which serves as the holding pen of the five daughters of fortune after they are abducted, black hoods over their heads, from the pleasure craft—seem to have been plucked from the discothèque or Yves Saint Laurent’s atelier. Cattrall’s character, Joyce, is the child of a US Senator, played by John Lindsay, the mayor of New York City from 1966 to 1973, in his first—and, understandably, last—screen appearance. Similarly, Rosebud is the lone film script credited to Erik Preminger, Otto’s son, who was born in 1944 and is the product of Dad’s adulterous relationship with the burlesque performer Gypsy Rose Lee; sworn to silence by the striptease artist, Otto didn’t meet Erik until 1966. (Distinguished lineages also mark Rosebud’s source, the 1974 novel of the same name by Joan Hemingway and Paul Bonnecarrère: the former is the granddaughter of Ernest and the older sister of actresses Margaux and Mariel; the latter, a French writer and journalist who died in 1977, is the maternal grandfather of the filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve, who directed Huppert in 2016’s Things to Come.)

Richard Attenborough as Sloat in Rosebud. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

Several real-life people, events, and groups from the early ’70s are invoked throughout Rosebud, namely the terrorist organization Black September, which supports the PLA and is here led by a roly-poly megalomaniac Brit named Sloat (Richard Attenborough), who insists that he has been chosen to “eliminate Israel” and “regain Arabia.” The mention of King Hussein and Lufthansa hijackings may ground the viewer in the film’s convoluted geopolitics, but it’s frequently impossible to tell just where, exactly, globe-trotting Larry Martin has landed. (Yet he will reliably declare, within seconds of leaving the airport, that he must get back to Paris.) And even when his coordinates are legible, his activities baffle: a detour to Hamburg, as best as I could gather, was necessary to track down the anti-Semitic cartoons of an outfit called the Franco-Belgian Society for Graphic Arts, sleuthing that entailed threatening to out an uncooperative photo-shop proprietress with a predilection for bedding her teen-girl employees.

Right: Peter O’Toole as Larry Martin in Rosebud. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

However ludicrous, Preminger’s movie benefits too from coincidental timing, reflecting actual, contemporaneous episodes that were themselves deranging in an already turbulent epoch. Rosebud went into production the same year that nineteen-year-old Patty Hearst, granddaughter of the outsize newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, was kidnapped in her Berkeley apartment by the Symbionese Liberation Army, its acronym only one letter away from PLA. (More odd concurrences: Granddaddy Hearst is, of course, the partial inspiration for Citizen Kane, the film whose famous, cryptic uttered word gives Preminger’s movie its name.) At one point Huppert’s Helene dons a dark wig not too dissimilar from the one that Patty Hearst, under the SLA nom de guerre Tania, wore in the famous surveillance photo depicting her robbing a San Francisco bank. Cattrall’s Joyce, the lone American among the five captives, may be Patty’s closest analogue—but the fictional privileged daughter, blithely doing sit-ups and singing Harry Nilsson’s “I Guess the Lord Must Be in New York City” to keep her body and mind fit during her Corsican imprisonment, enjoyed an internment closer to Outward Bound, while the real heiress endured unimaginable trauma.

Left: Isabelle Huppert as Helene Nikolaos in Rosebud. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

During Rosebud’s making, Cattrall and Huppert suffered the abuses of a genuine terrorist: Preminger himself, an on-set tyrant who proudly boasted, “I don’t get ulcers, I cause them.” On a 2014 episode of the Talkhouse Film podcast, they recount the director’s volcanic temper. The unpleasant experience forged a friendship between the two young actresses, who remain close to this day. Unlike Patty Hearst, they did not fall victim to Stockholm syndrome—never bonding with Preminger, their captor, but with each other.

Melissa Anderson is the film editor of 4Columns.