Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

On her new album, the weight of fame and getting high in the parking lot.

Lana Del Rey

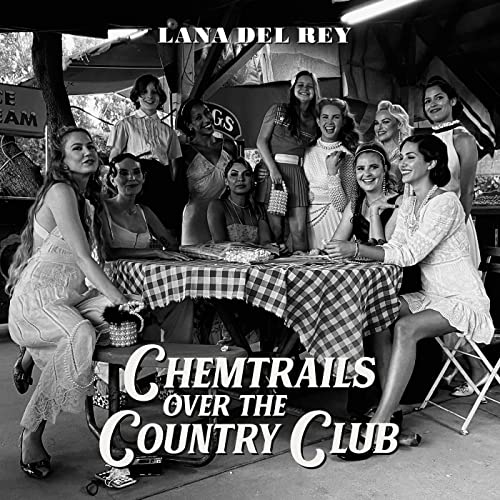

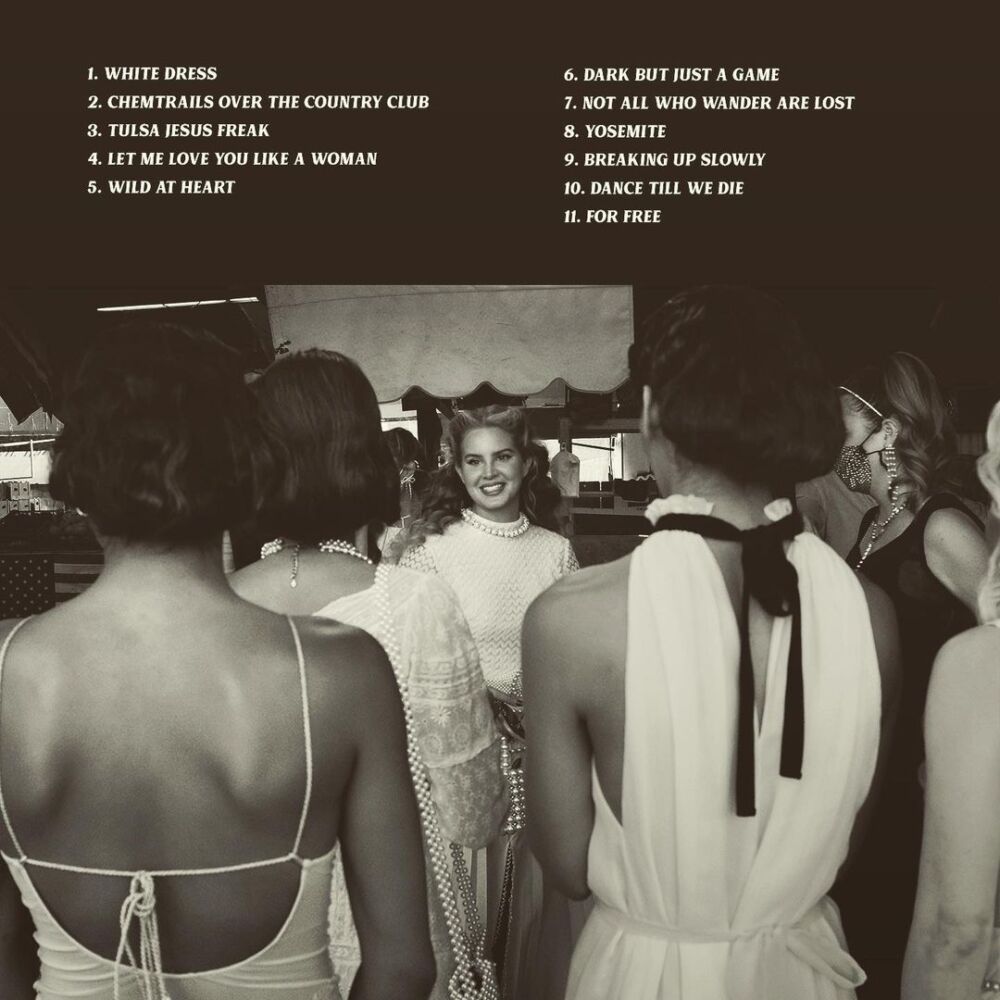

Chemtrails Over the Country Club, by Lana Del Rey, Interscope/Polydor

• • •

Lana Del Rey, like director John Woo, is a maker of worlds. His films are satisfying because of the doves and slow motion and flames, not despite them, and Del Rey’s emotional baroquery is equally legit. As soon as she debuted in 2011, she started speaking about her affinity with rappers, and it made absolute sense—she brought the magic of talking shit to pop melodrama. Why couldn’t Dusty Springfield be from Twin Peaks? Why couldn’t you have God, youth, diamonds, and summertime all fighting for dominance in one song? When Woo adds two backflips to a motorcycle chase, we don’t blink, and when Lana sings, I never wonder if my American sweetheart was really born to die.

Del Rey fought off the authenticity scolds and used the keywords of American swagger to hotwire the Tumblr aesthetic. She knows how to bring totems to life, and on her new album, Chemtrails Over the Country Club, she does it with Jack and Coke, ranches, Tammy Wynette. What she’s created over time is a mythology extracted from the guts of pop music and a fully formed, instantly identifiable musical strategy. Del Rey sets her drama in the center of an audible soft focus for which she still hasn’t gotten enough credit.

But she became our Karen of the Canyon. In 2019, Del Rey started asking for the manager and calling out journalists who didn’t kiss the ring. In an interview with the BBC’s Annie Mac earlier this year, she told listeners that “the most important thing” she had to say was that the January 6 insurrectionists felt a “disassociated rage” and wanted “to wild out somewhere.” This is a notable take on a group of small-business owners who brought a Confederate flag into the Capitol and left shit in the halls.

These are outside issues, though—Chemtrails is Lana’s world, and her frame is sturdy. Lana rarely stumbles as a musician, especially in collaboration with Jack Antonoff, who understands the nutty power of her lower register. There isn’t a single Del Rey album that doesn’t feel like a shag rug soaked in camphor, a style many go for without success. Slow songs? There are no fast Lana songs. Queens don’t run!

Lana Del Rey

On Chemtrails, though, I can’t tell who’s home. In “White Dress,” the album opener, Lana sings about “a simpler time,” when she “wasn’t famous,” just nineteen and listening to Kings of Leon. These are the days of Lizzy Grant, walking around Orlando, “down at the men in music business conference.” It’s a great line and a real joke when she sings it twice, quickly, in a falsetto that barely flies. The tentative nature of the song draws you in, and its ending presents a fascinating double helix. Del Rey sings that she would “still go back,” because being nineteen and dunking on dumb music men “made me feel like a god,” which is something she seems to be now. She’s idealizing the past while leaning a lot on the words “here” and “now,” a thin perch for an entire album.

Del Rey goes on to tell us she’s from a “small town,” but most of Chemtrails sounds like the voice memos of an heiress barricaded in the compound, bonding with friends over benzos while a sunset lamp points at the floor. “Dark but Just a Game” is apparently something Antonoff said about the nature of fame, and the song spins this idea in the world of Lana you know and love, where events are only lightly sketched. “I was a pretty little thing and God, I loved to sing / But nothing came from either one but pain (But fuck it).” There is “no rose left on the vines,” and Del Rey is not having a good time. Her solution: “And while the whole world is crazy / We’re getting high in the parking lot.” If that is her reaction to fame, more power to her, but as a reaction to the whole world, it’s an odd choice for 2021. Later, on “Yosemite,” a song that (maybe) unpacks a long relationship, she asks, “Isn’t it cool how nothing here changes at all?” It’s hard to imagine that many people, other than Del Rey, are feeling as if nothing changes right now.

In “Dance Till We Die,” Del Rey sings about “covering Joni” (Mitchell) and “dancing with Joan” (Baez) and that ranch that comes up in several songs. Del Rey and Antonoff build up a fantastic track, with a mellotron and horns hovering at the edge of the audible. “Troubled by my circumstance / burdened by the weight of fame / Clementine’s not just a fruit / it’s my daughter’s chosen name.” I can’t decode the Clementine bit, but the fame story is clear enough and of a piece with the other complaints. The regal dismissals are fun, so if she’s your queen, the dramatics are kind of delicious. I just hear a master of affect trying to move into a confessional mode that doesn’t exploit what made her interesting in the first place: the ability to write a song with the symbols of vibe rather than the specifics of experience. She climbed Olympus but now seems to want to be One of Us. Pick a mountain!

The decision to end on a cover of Mitchell’s “For Free” highlights that gap between general and specific. Del Rey’s cloudy touch doesn’t line up with Mitchell’s ear for concrete details. (Why in the world would Lana Del Rey ever notice any children?) Joni has always been on the ground with us, parsing daily life, while Lana rules a nighttime world of idealized selves at war. Asking daily life and dreams to occupy the same space seems kind of pointless. I, for one, miss when her songs worked in so many variations of the romantic without suggesting any particular person. I’m not sure Lana Del Rey needs to be real!

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.